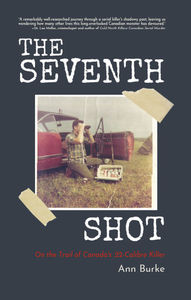

Excerpt: Ann Burke's The Seventh Shot: On the Trail of Canada's .22-Calibre Killer Digs into a Killer Cop's Horrific Crimes

Ann Burke's The Seventh Shot: On the Trail of Canada's .22-Calibre Killer (Latitude 46 Publishing) goes back in time over thirty years to two horrific crimes that wouldn't be solved for decades to come. What investigators didn't know at the time was they were pursuing a police officer, the man who murdered two mothers in their homes while their children were under the same roof.

Burke has a personal connection to the killer, having once been a classmate of his, and her research is extensive, drawing on archives, interviews, and more. The Seventh Shot takes readers into a determined investigation that finally bore fruit thanks to detectives' meticulous preservation of DNA evidence, but it also delves into the life of the killer, Ronald Glen West: his young life, his time as a traffic cop, the vicious string of robberies that landed him in jail before his murderous past was discovered, and much more.

A chilling true crime story set in supposedly quiet and tranquil Ontario towns, The Seventh Shot is a deep dive into an often over-looked serial killer's brutal legacy.

Content warning: violence and sexual violence

Excerpt from The Seventh Shot: On the Trail of Canada's .22-Calibre Killer by Ann Burke:

CHAPTER FOUR: The Mother Thief

“Do you remember running from our house? I do. It’s clearer than my first kiss, the birth of my kids, or what I had for lunch today.”

—Dale Ferguson, Brampton Courthouse, August 7, 2001

When attempting to reconstruct the sequence of events that day, it was presumed that upon encountering Helen, her assailant learned she was home alone with a sick child, and that he proceeded to tell her he was going to rape her, and to refuse or make a fuss would result in the death of both her and her son. The police also thought it was possible Helen made up the story about the sick boy in the car so Dale would not become unduly alarmed and get out of bed to see what was happening.

It was conjectured they next went upstairs to the bedroom at the west end of the house, to a room full of flowers and sunlight. The top sheet, blanket, and bedspread were thrown over the far side of the bed. Helen’s blouse and slacks, both inside out, were found with her untied running shoes, bra, and panties, all in a heap on the floor near the head of the bed, which the police believed indicated that the assailant undressed her. One of the bed pillows was missing and found later to be on the living room couch, possibly indicating that Helen, reportedly not feeling well earlier that morning, had brought it downstairs earlier to rest her head on.

After being raped, Helen preceded the man downstairs, possibly believing the nightmare to be over. She was dressed only in her housecoat, which was not done up, and a pair of socks. All indications suggested that as Helen reached the bottom step, hopeful her ordeal had ended, the assailant shot her in the back of the head at close range, from only the second or third step immediately behind her.

He fired two more shots into Helen’s back as he stood above her before fleeing the house. It was thought that a crash, which Dale reported hearing during the shots, may have been the sound of Helen falling against a divider loaded with glassware and sitting at the bottom of the stairs. Several scrapes on Helen’s right leg were thought to be indicative of this theory.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

While studying the police photos, I noticed the purported shelf/divider gave no indication of having served as a factor of Helen’s injuries. In fact, nothing at all appeared out of place amongst the ornaments, vases, and bric-a-brac it held. Even though Helen’s body had been removed before the police photos were taken, who would have replaced all the items symmetrically on the shelves?

—Ferguson Residence - Bottom of Stairs. (OPP Archives)

—Ferguson Residence - Chalk Outline. (OPP Archives)

Another puzzling factor within the same police photograph: the drawn outline of Helen’s body and the blood-soaked carpet are well beyond the base of the stairs. Helen may have been moved by Russell from the confined space when he attempted to get a heartbeat. What can definitely be determined from the crime scene picture is that Helen’s body was removed before the identification unit arrived. This alone would allow for potential confusion.

As in the Moorby case, no empty cartridges were found at the scene and all indications were that the weapon was a revolver. Dale did not report seeing the man carrying a weapon but believed his pants pockets were bulging. It was estimated Helen’s murderer had been in the house for approximately twenty-five minutes, and most of the time was spent in the bedroom.

When the police looked for any indication of theft, Russell would suggest that as much as forty dollars may have been missing from Helen’s purse in the bedroom. This, however, was never established as a certainty. Similar to the previous murder, no confirmed signs of theft were evident.

Something that did stand out in the crime scene photos were several vases of flowers—perhaps due to Mother’s Day— reflecting the propensity for floral wallpaper throughout the home.

A post-mortem examination was made on the body of Helen Ferguson on the evening of Tuesday, May 19, at Dufferin Area Hospital in Orangeville, and conducted by Dr. G. M. Longfield of Brampton.

Helen had been shot three times. The first bullet had passed through the centre of the skull at an angle such that, if it had continued, it would have come out of the right eye; a second bullet entered her back, just below the base of her neck and to the right; and the third bullet entered just below the second. Helen’s housecoat had two corresponding bullet holes with close-range powder residue at both bullet entry points.

Once again, Corporal Charlie Rowsome of the OPP painstakingly collected and preserved the evidence from the crime scene. As with the Moorby case, the murderer was identified to be an A-type secretor, and the bullets removed from Helen were identified as being .22 calibre. This information would lead to the assailant being dubbed “The .22-Calibre Killer” by the media and, in turn, the public. Furthermore, it was established that the same 9-shot handgun had been used in both cases.

The murderer had made more efficient use of his weapon this time, but the results were the same: a little boy was left without a mother, and this time with siblings to share the devastating loss.

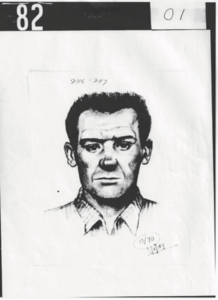

Dale Ferguson was to describe the intruder to sketch artist Detective Sergeant Joseph Majury of Metro Toronto Homicide, who drew a composite of the suspect. Majury described Dale as “a remarkably astute and bright young man.” Dale felt satisfied the composite sketch accurately identified his mother’s killer. Photographs of the boy appeared in newspapers: a fair, tousle-headed, smiling child, seemingly without a care in the world.

Dale’s description of the man was as follows: Age: 38 to 42

Height: 5’8” or 5’9”

Build: Medium

Weight: About 160 lbs

Complexion: Dark, in need of a shave

Hair: Black, the style resembling a brush cut growing out

Speech: A deep voice, and may have had a slight accent

Clothing: Wearing what appeared to be a greyish blue sport shirt with yellow and white stripes and dark grey dress trousers Dale added that “the man looked as if he had been in a lot of fights.”

—Sketch by Detective Sergeant Joseph Majury of Metro Toronto Homicide, based on description by Dale Ferguson. (Ontario Archives)

_________________________________________________

This excerpt is taken from The Seventh Shot: On the Trail of Canada's .22-Calibre Killer by Ann Burke, copyright © 2020 by Ann Burke. Published by Latitude 46 Publishing. Reprinted with permission.

After serving in the Royal Canadian Navy as a Navigational Operator/Radar Technician, Ann Burke turned her interest to her greatest love, writing. Working largely in the social services sector as a counsellor in a Women and Children's Shelter, co-ordinating a Homeless drop-in and directing a rural community centre, she freelanced for newspapers, including The Toronto Star. Her most memorable years were spent working for The Walden Observer in Lively, Ontario and covering events for The Sudbury Star. She now lives in Innisfil with her husband.