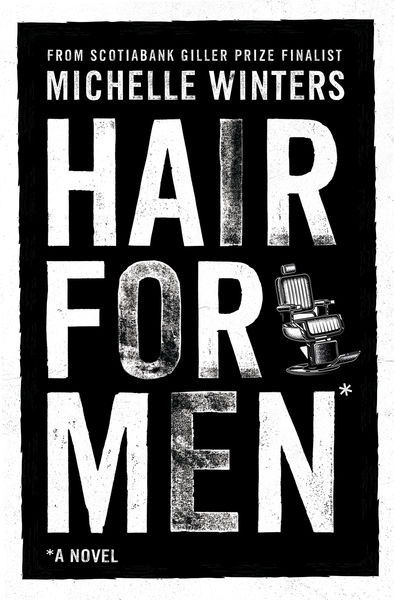

Giller-finalist Michelle Winters Balances Love and Rage in her New Novel, Hair For Men

Already lauded for her first novel, Scotiabank Giller Prize finalist Michelle Winters is back with a powerful and profound story about love and rage, and a young woman battling her own traumatic past and a deeply-flawed society to find some measure of catharsis.

In this new work, Hair for Men (House of Anansi Press), we follow Louise as she goes headlong into the anger and discontent of the Toronto hardcore punk scene. She lives amidst its inherent violence until she stumbles into a mysterious men's hair salon by chance, and encounters a clientele that offers some hint of a better world. But when even this respite is ruptured, Louise decides to escape to the East Coast, finding a marina where she can camp out and try to cope with the past. Then, on the fateful day of the Tragically Hip's farewell performance in Kingston, a man from the Bay of Fundy appears and stirs deep, long-lost feelings that may lead to redemption and atonement after all.

It's a subversive, explosive, and beautiful exploration of how to throw off the trappings of a complicated life, all while exploring gender, desire, anger, and forgiveness.

We're all charged up to share this Long Story Novelist Interview with Winters, right here on Open Book!

Open Book:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

Michelle Winters:

I was born in Saint John, N.B. and grew up sailing the Saint John River, as well as the actual Atlantic Ocean. I’m artistically inclined toward bodies of water, both the lazy and terrifying ones. I think I always knew I’d write about the Bay of Fundy, because it has such vividness of character – there’s the Reversing Falls themselves, this swirling current propelling these super dramatic tides, then just past the Reversing Falls, there’s a line where the bay becomes the Atlantic and the water actually turns from river black to ocean green. Even as a child, before I ever knew I’d write anything, I recognized the poetry of that waterline. Furthermore, some portion of my youth was misspent at the boat club, watching drunken adults, which was almost as mystifying as the ocean itself. I also knew I’d one day write about drunken adults at the boat club.

There’s a lot of fertile ground in Toronto, from its healthy hardcore punk scene for Louise to stomp around in, the normal-normalness of Mimico as a place for her to grow up, and the haunting anonymity of industrial Mississauga for the salon. If you’ve ever walked industrial Mississauga, it’s all factories and wholesale depots and storage facilities… it’s a wasteland as far as human colour goes, creating a nice juxtaposition with the vibrancy of the salon itself. Since it’s out near the airport, it’s a good location for nameless enterprises servicing traveling businessmen seeking anonymity. Mississauga is almost as fascinating as the ocean and drunken adults! I also like the tension between Toronto and the Maritimes (well, Toronto and every other part of Canada). There’s a feeling on the East Coast that anyone who moves out East from Ontario has ‘finally made the right decision’. It has a feeling of home (maybe that’s just me), and I wanted Louise to finally have a home.

OB:

Did you find yourself having a "favourite" amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

MW:

I love them all, of course, but Louise was by far the most intense. Writing through the eyes of a character that angry takes you to a whole different vicarious place that was frankly pretty cathartic to explore. It’s a valuable exercise to empathize with someone who considers violence a regular option, like playing an avatar who does what you’re not allowed to in real life. I hope that experiential aspect of Louise transmits in the reading.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

And I know “favourite” doesn’t mean “more than one”, but important mention goes to Mitch. Hair for Men rides on a balance of Louise’s profound love of men and her homicidal rage. Writing Mitch meant creating both a villain and a man trapped by the system that rewards him. He’s extremely complex and tested my sympathy in ways I wasn’t expecting.

OB:

If you had to describe your book in one sentence, what would you say?

MW:

It’s the story of a woman who loves men and also wants to beat them up.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

MW:

- I watched the YouTube video of the final Tragically Hip show in Kingston over and over, timing the songs with the events in the story and the way the mood shifts as the show goes on. I also listened to a ton of The Tragically Hip while out walking, paying very close attention to the lyrics, just eating those songs. The book is crammed with Easter eggs.

- I read bell hooks’ The Will to Change, where she argues that the patriarchy hinders men’s true happiness and ability to know themselves. Then I read it again. I balanced that out with a number of classically masculine books (Fight Club, Hesse, Hemingway, Salinger, Steinbeck) along with some ocean-faring texts (Joshua Slocum, Bernard Moitessier) and, of course, Get in the Van, Henry Rollins’ account of his five years touring with Black Flag.

- I read a dissertation called Henry Rollins Rhetoric of Atonement, by Mark Glantz. Henry Rollins issued an apology for a deeply insensitive article he wrote about Robin Williams’ death by suicide in 2014, and that apology made itself academically noteworthy for his acceptance of responsibility, avowal to do better, and appeal for forgiveness. Once I realized Hair for Men was about forgiveness, this text became like a guide.

- Men, men, men.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

MW:

I dedicated it to my dad, who arm-wrestled and foot-raced me, and molded me for the good and the less-than-good.

OB:

Did you include an epigraph in your book? If so, how did you choose it and how does it relate to the narrative?

MW:

When I started writing, I had three possible epigraphs:

- “Indelible in the hippocampus is the sound of laughter.” - Christine Blasey Ford

- “Yeah, you throw like me!” – Lisa Simpson

- “My optimism wears heavy boots and is loud.” - Henry Rollins

When Christine Blasey Ford testified against Brett Kavanaugh in that Senate Judiciary Committee hearing when Kavanaugh was nominated for the Supreme Court, she was asked what she remembered from the sexual assault committed by him and another dirtbag at a party in high school. She came up with that sentence instantaneously. She could clearly still hear that laughter. Those words – and her willingness to testify despite the consensus that her attack wasn’t all that bad - haunted me. I wanted to shout her out in this book, but in the end, it was just too sad. And infuriating.

The Lisa Simpson quote crystallizes the notion that there’s no more dreaded comparison for a man than to be likened to a woman, making it a hilariously apt and tragic insult for a woman to wield. It speaks to the feelings Louise has for her own femininity and her effort to dissociate herself from it, in order not to be victimized. But again, much too sad.

The quote from Henry Rollins speaks directly from the best part of Louise with just the right blend of positivity and aggression.

______________________________________________

Michelle Winters is a writer, painter, and translator born and raised in Saint John, NB. Her debut novel, I Am a Truck, was shortlisted for the 2017 Scotiabank Giller Prize. She is the translator of Kiss the Undertow and Daniil and Vanya by Marie-Hélène Larochelle. She lives in Toronto.