Helen Humphreys' Field Study Digs Through History Via the Connection Between People and Plants

Whether you've got a home filled with flourishing plant babies or a few bits of dried wheat in a jar, it's hard to deny the power of plants have to effect our mood and surroundings.

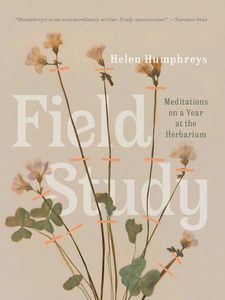

Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium (ECW Press) by acclaimed novelist, poet, and nature writer Helen Humphreys delves into a forgotten aspect of that human-plant relationship, with Humphreys discovering her local herbarium and becoming fascinated with the 19th and 20th century practice of collecting plant specimens. With enthusiasts like Dickinson and Thoreau amongst the keen collectors of the past, Humphreys finds plenty of material for her investigation into the common yet treasured plants of the past, some of which have been lost to us forever.

Humphreys even includes intricate and stunning botanical illustrations of her own in the text, as well as archival photos and more. A meditative journey into history through a green lens, Field Study is a must for nature lovers and we're excited to present an excerpt here today, courtesy of ECW Press.

Excerpt from Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium by Helen Humphreys:

My interest is in showing the intersection between nature and people, between the plant and the collector. This field study is not a comprehensive document of every plant and collector, but is instead my response to what I have found gathered and catalogued within those white cabinets. I have treated the Fowler Herbarium as a kind of wilderness, following particular threads that catch my imagination and curiosity. I want to show how exploring an archive can be a journey, as thrilling as any taken in an actual landscape, and that no two journeys are alike. My decision to use the herbarium as a wilderness is my particular path. Another researcher or writer would choose a different direction. There is no right or wrong way to go about this kind of exploration. It is a matter of choices made and the interest and intent that informs those choices.

Fern

(Tracheophyta)

Fowler Herbarium

Mosquito Fern

(Azolla pinnata)

Fowler Herbarium

When I begin to look through the herbarium cabinets, beginning as the collection does, with Ferns, I am struck by how the plants are layered on top of one another in the files, like a cemetery, with each large, metal cabinet becoming a sort of mausoleum. Everything is dead – the plants and the collectors themselves, who are preserved with the briefest flicker of ink on their specimen labels. All of these people and plants, who were placed nowhere near to one another in life, are now jammed up against one another in death.

Here is William Starling Sullivant, who became a botanist after watching a man collecting plants in a field outside his house while he was eating dinner. Sullivant rushed outside, leaving his uneaten plate of food on the table, and then invited the stranger in to dine with him and explain his botanizing.

Now it is September 18th, 1841, and Sullivant has written a long letter to accompany the specimen of Carolina Mosquito Fern (Azolla caroliniana) that he has just scooped from a flooded meadow in Columbus, Ohio. The letter begins with an ink drawing of a hand, with the index finger pointing to the body of the letter, which explains at length how Sullivant has been watching this particular patch of Mosquito Ferns since 1840 and now, a year later, they are finally displaying reproductive organs and so he has decided to capture them and has glued several examples onto paper for his private herbarium.

And here is a Beech Fern (Phegopteris dropteris) collected by Sir Charles James Fox Bunbury on June 10th, 1844 from Ambleside, Cumbria, in the northwest of England. The fern was picked from the base of Stockgill Force, a seventy foot high waterfall that so impressed John Keats when he saw it on a walking holiday in 1818, that he vowed to try and write poetry to honour it and said of the sight of it – “What astonishes me more than anything is the tone, the coloring, the slate, the stone, the moss, the rockweed; of, if I may say so, the intellect, the countenance of such places.”[1]

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The Beech Fern grew in great abundance at Stockgill Force in the 1800s, so Bunbury’s finding it was not made difficult by scarcity.[2]

The Victorians had a passion for “ferning,” and those with the means often had their own greenhouses and grew their own ferns to study and draw. Ferns were a fad, a fascination with the “exotic” and bringing that exoticism back to Britain. It was a botany of empire.

Beech Fern

(Phegopteris dryopteris)

Fowler Herbarium

In Australia, Baron Ferdinand Von Mueller’s collecting team of men and women were picking a Drooping Filmy Fern (Hymenophyllum demissum) in the Upper Yarra Valley in Melbourne, to add to his extensive herbarium, which he called the “Phytologic Museum of Melbourne.” Later it became the National Herbarium of Victoria, when he was appointed Government Botanist of Victoria in 1853. At the time of Mueller’s death in 1896 it contained close to one million specimens and can still be visited today. Von Mueller had relied, as many of the European botanists had, on a vast network of 3,000 people to collect plants for him, largely amateur botanists.[3] He appealed particularly to women, putting an ad in the Brisbane Courier in April 1872 that read in part: “What trouble would it be to collect and preserve flowers, and enclose in an envelope to their destination? How many ladies might devote a few leisure hours to this pursuit? Every contribution would be acknowledged, and not only that, but the donor’s name become a part and parcel of this great undertaking.”[4]

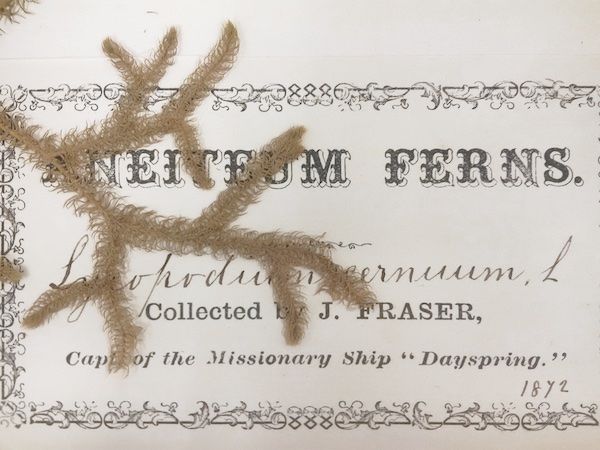

In Canada, in 1862, a missionary ship called the “Dayspring” was built in the New Glasgow shipyards in Nova Scotia with funds raised by the Presbyterian Church. It was a large ship of 120 tons, a three-masted schooner or “barque”, bound for a group of islands in the South Pacific known as the “New Hebrides,” and now called Vanuatu. Once there, the missionaries encountered slavers who were coercing the islanders to board their ships, transporting them to work in the cotton plantations of Fiji and the sugar plantations of Australia. The missionaries from Nova Scotia were anti-slavery and the crew of the “Dayspring” tried to warn the islanders about the trafficking, while also persevering in their mission to convert them to Christianity[5].

The “Dayspring” was captained by a William A. Fraser, a former smuggler from Nova Scotia, described as “a bold fellow, and ready for anything yet thoroughly honest and upright.”[6]

Fraser collected ferns while he was in the South Pacific, and the Stag’s Head Fern (Lycopodium cernuum) in the Queen’s herbarium collection was plucked from the jungle floor on the island of Aneityum in 1872. This small island, just 61.5 square miles, was reported to have once contained over a hundred different species of ferns.[7]

A year after the Stag’s Head Fern was picked by Captain Fraser, the “Dayspring” was wrecked beyond repair in the Aneityum harbor during a hurricane. Fraser decided to retire at this point, and returned to Nova Scotia.

Botanical label from the Fowler Herbarium

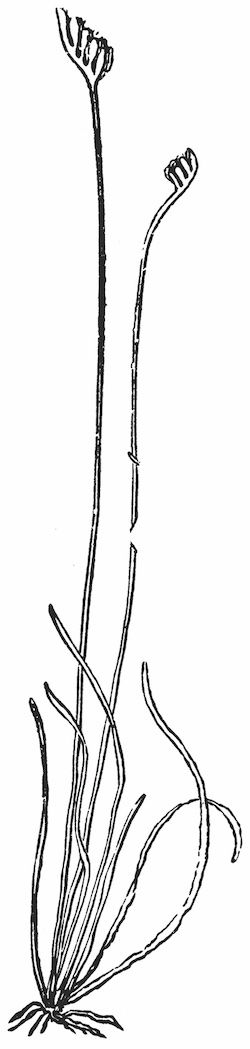

In New Jersey in the 1870s, Mary Treat collected a Small Curly Grass Fern (Schizaea prusilla). She was one of only four American woman botanists who were publishing before 1880, and who earned enough from her books and scientific articles to support herself after her husband left her for a younger woman when she was forty-four.

Mary Treat was self-taught, but well respected by professional botanists. She was in correspondence with both Charles Darwin and Asa Gray, the famous American botanist. She didn’t believe in ranging far for her specimens, spending most of her time in her own garden, botanizing and writing about her observations there. She believed that observing a small place yielded better results than travelling over a large area. “The smallest area around the well-chosen home will furnish material to satisfy all thirst of knowledge through the longest life.”[8]

curly-grass fern

(Schizaea pusilla)

Asa Gray

In 1903, Alfred Brooker Klugh picked a Cinnamon Fern (Osmundastrum cinnamomem) from a place in Ontario he called “Indian Pipe Swamp.” This was his name for the place, so there is no knowing where it actually was. An additional note on his collector’s label, in someone else’s hand, guesses that the location was somewhere in Puslinch township, in Wellington County, Ontario.

A.B. Klugh, as he is known on his collecting labels, came to Canada from England with his parents when he was twelve. He graduated in nature study from the Ontario Agricultural College, following with an M.A. from Queen’s University and a Ph’D from Cornell University. He taught as an associate professor in the botany department at Queen’s until his death at the age of fifty, when the car he was traveling in was hit by a C.N. train at a rail crossing in Kingston.

Klugh picked this Cinnamon Fern for his own herbarium on July 16, 1903, when he was twenty-one years old. According to historical weather data the day was cool for summer, with a mean temperature of just 14.2 degrees Celsius, clear and without any rain.[9]

The Cinnamon Fern is a large fern that grows in clumps in wetlands. It gets its name from a single upward frond, or pinnae, that is cinnamon coloured. The rest of the fern is green.

It is not hard to imagine this fern, growing amid other ferns, in a swamp that was also filled with Indian Pipes, a plant so pale and otherworldly that it is also called the Ghost Plant or Corpse Plant. (It is so white because it doesn’t produce chlorophyll as green plants do). Into this swamp, on this cool July day, strides the young botanist, Alfred Klugh, at twenty-one almost halfway through his brief life. And here is this moment – the fern reaching up, the hand reaching down. And then the note on the location, a place Klugh names for himself, a place that now only exists here, on this scrap of archival paper, in this blue file folder.

______________________________________________________________

Excerpt from Field Study: Meditations on a Year at the Herbarium by Helen Humphreys, published by ECW Press. Copyright 2021, Helen Humphreys. Reprinted with permission.

Helen Humphreys is the author of 19 works of fiction, non-fiction, and poetry, including Rabbit Foot Bill and The Frozen Thames. She has won the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize, a Lambda Literary Award for Fiction, and the Toronto Book Award, and has been shortlisted for the Governor General’s Award, the Trillium Book Award, and CBC’s Canada Reads. She is the recipient of the Harbourfront Festival Prize for literary excellence. Humphreys lives in Kingston, Ontario.

Footnotes:

[1] Letter from John Keats to his brother, Tom, on June 27th, 1818

[2] A Natural History of New and Rare Ferns by Edward Joseph Lowe; Groombridge and Sons; 1865

[3] Collecting Ladies: Ferdinand Von Mueller and Women Botanical Artists by Penny Olsen; National Library of Australia; 2013

[4] Ibid, pg. 10

[5] Faith and Slavery in the Presbyterian Diaspora by William Harrison Taylor, Peter C. Messer; Rowman & Littlefield; 2016

[6] Diary of William Norman Rudolf; William Norman Rudolf fonds; Nova Scotia Archives

[7] In the New Hebrides: Reminiscences of Missionary Life and Work, Especially on the Island of Aneityum, from 1850 Till 1877 by John Inglis; T. Nelson and Sons; 1887

[8] Home Studies in Nature by Mary Treat; New York; American Book Company; 1885

[9] Government of Canada, Historical Weather Data