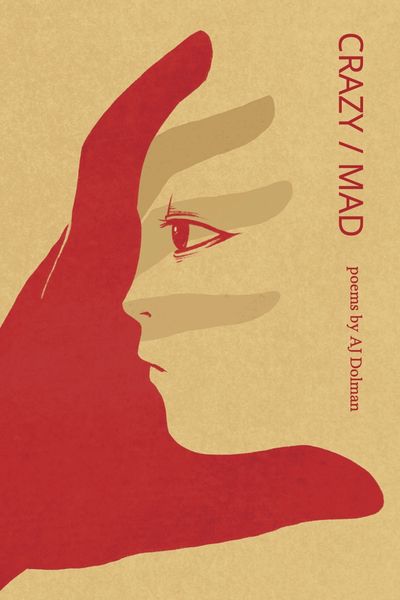

In Crazy / Mad, AJ Dolman Challenges Poetic and Societal Norms, and Offers Hope

In this day and age, mental health, gender, sexuality, and other important social issues are acknowledged more than they were in the past. However, there is often little truly honest engagement with the actual systemic and societal problems that are causing illness, fear, and distress for so many people.

With their new poetry collection, Crazy / Mad (Gordon Hill Press), AJ Dolman looks squarely at all of this and uses their words as a form of resistance, pushing back against the norms and standard of the form, while also challenging the ways that people are treated in the modern world.

Delivering poems that get right to the heart of the troubles and crises that we face in our daily lives, the collection serves as a point of hope for “the worried, the lost, the uncertain, and the afraid."

Read more about this essential work in this Line and Lyric interview with the author:

Open Book:

Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your title? If it’s a title of one of the poems, how does that piece fit into the collection? If it’s not a poem title, how does it encapsulate the collection as a whole?

AJ Dolman:

The dualities of meaning in Crazy / Mad signify the fury, mental illness and joy I tried to convey in the collection. A comment on the amazing adventure life can be, the pairing also represents, equally, a raging against biases and obstacles, and me owning my mental illnesses.

We talk lately about “destigmatizing” mental illness, but that mostly seems to mean chatting with a friend when you’re a bit down. We’re still not taking an honest look at what is causing, and what to do about, suicidality, the enormous and population-skewed rates of depression and anxiety, the rise in bipolar and other disorder diagnoses, let alone what to do for folks with psychosis, schizophrenia and a range of other life-threatening diseases. At the corporate and political level, we hope to make a mental illness pandemic go away by promoting yoga and herbal tea, or prescribing a day at the spa and some “me time.”

My diagnosed mental illnesses—chronic depression and anxiety and panic disorder—are both inherited and environmental. My triggers seem obvious. We live at the nexus of nonstop hypercapitalism, where we are viewed only as pieces in an economic system that benefits at most a handful of powerful people, and a perpetual onslaught of trauma. My parents grew up in the second World War, in Nazi-occupied eastern Netherlands. I grew up with their trauma, their stories, their pain, and also the daily news of how we were irreversibly destroying our planet. And we have. We are. Both environmentally and through hate, be it manifest in hate crimes or wars. How are we supposed to keep functioning amid this? I feel like downward dog, as helpful in the moment as it may be, isn’t dealing with the bigger problems.

I had a good friend, singer Lori-Jean Hodge, who passed away from cancer several years ago. She used to say “It’s crazy madness” whenever something really excited her.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I am literally, textbook definition, crazy, but so many of us are. I am also painfully mad. Furious. That we as a species have done this to ourselves, destroyed so much for the sake of a global game of monopoly. But I am hopeful, too. Because this is a wild ride, this life. It’s still ful l of opportunities for learning and beauty and general magnificence, particularly when we get to connect with other human beings, particularly when their journeys are different to our own. I’m still willing to fight for that, for our existence and our potential. I’m still willing to fall down and keep getting back up until I can’t anymore, to keep making mistakes and then trying again. It’s crazy madness, but I’m in, and I know others are, too.

OB:

What was the strangest or most surprising part of the writing process for this collection?

AJD:

The reception of the poems individually and as a whole has thrown me. Both the anger and the experience of being afraid of being categorized, labeled and determined unfit (based on any types of bias) clearly resonate with people in a way I don’t know that I was prepared for in real life. I am deeply grateful for it, though sad, of course, for every individual’s painful experiences. It makes me want to help improve the world in whatever small way I can, though. The first thing I can do there is to look at my own biases and not be so afraid to realize them, so I can combat them.

OB:

Did you write poems individually and begin assembling this collection from stand-alone pieces, or did you write with a view to putting together a collection from the beginning?

AJD:

It was a matter of some brilliant editors and readers pointing out the recurring themes in my poetry at the time, and then learning to embrace them. In this as in so many ways, am quite terrible at seeing myself clearly, I think.

OB:

What's more important in your opinion: the way a poem opens or the way it ends?

AJD:

Neither. It is the feeling it leaves you with. And that can resonate most deeply from any or all parts of the poem, from where the poem fits into a collection or anthology, and from the reader’s own experiences combining with the moment they meet the poem.

I am dubious of all defined endings, honestly. What really ends in reality? And where does anything truly begin? It’s the overall sense of the thing that sticks with us. Sometimes the thing is an entire suite of poems; sometimes it’s a single phrase.

OB:

Who did you dedicate the collection to and why?

AJD:

I dedicated it to “the worried, the lost, the uncertain, and the afraid.” This is a book I may have needed when I was each of those things. I hope it gives something to readers who have been, or are, at those points as well. I very much believe in the idea that none of us can truly be free until all of us are free. I can only offer so much toward that goal as an individual, but as a poet I can at least offer words towards making myself and others, if not more free, then at least more seen and, hopefully, respected.

OB:

Is there’s an individual, specific speaker in any of these poems (whether yourself or a character)? Tell us a little about the perspective from which the poems are spoken.

AJD:

I’ve talked before about how, when I came into poetry in my early 20s, I was often told by self-nominated guardians of CanLit that confessional poetry was for navel-gazing diarists and people lacking perspective, etc., all of which I took to mean women and queer folk. The idea of speaking of yourself and your quotidian experiences of humanity had been relegated to the trash heap as populist dreck.

Owning my own narrative in a number of these poems feels like reclamation. Who were those usually white, male, straight, cis, macho poets to speak omnisciently? What will history eventually say of that sort of hubris?

I suppose the answer to the latter is that it depends on who will get to write that history. For now, I’m trying to contribute to it in my own way, and am unendingly thrilled reading the many perspectives of others.

OB:

Was there a question or questions that you were exploring, consciously from the beginning or unconsciously and which becoming clear to you later, in this collection?

AJD:

I think I thought I was asking why we (individually and collectively) are so miserable. Which is funny, because of course we all already know those answers, and it isn’t really what I turned out to be asking anyway.

Instead, I found myself exploring how and why we each go on. Not from a cheery framework of look on the bright side, and aren’t kids and puppy dogs adorable, or what about the flowers. But from the perspective of holy shit, look what we have (again, both individually and collectively) borne thus far. Better to keep going, perhaps, and see if we can’t turn this into something better.

_________________________________________________

AJ Dolman (she/they) is the author of Lost Enough: A collection of short stories and three poetry chapbooks, and co-editor of Motherhood in Precarious Times. Her poetry, fiction and essays have appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, including Arc Poetry Magazine, QT Literary Magazine, The Quarantine Review, Imaginary Safe House, Grain, Canadian Ginger, On Spec, Prism international, The Fiddlehead, Utne, Crush and The Antigonish Review. They are a bi/pan+ rights advocate living on unceded Anishinaabe Algonquin territory.