Jessica Westhead on Balancing Absurdity, Sensitivity, & Insight in Her Exploration of White Privilege

Just last week saw the launch of Avalanche (Invisible Publishing), a new story collection from Jessica Westhead. One of Canada's most innovative short fiction writers, Westhead has long crafted memorable casts of (mostly) harmless but odd misfits in her writing.

In Avalanche, however, the weirdness persists but the intentions and impact of her characters have shifted as she explores white privilege and entitlement, guilt, and misplaced coping amongst of a disparate cast of middle class white characters waking up (or refusing to do so) to the ingrained racism and colonialism of their societies.

With Westhead's signature wit and absurdity, she skewers white supremacy's feigned cluelessness and holds both characters and readers to account as she weaves moments of allegedly "polite" or quiet discrimination. The obliviousness of her characters acts as a societal mirror, with violence both literal and figurative lurking just out of frame in each tense tale. As white characters flail to have their own innate goodness confirmed, they encroach further and further on the patience, well being, and even safety of racialized characters. Unpredictable, expertly crafted, and executed with deadpan wit, Westhead's collection is a powerful and timely clarion call from one of our finest short fiction creators.

We're speaking to her today about Avalanche as part of our Keep It Short short fiction interview series, and she tells us about how exploring parental anxiety unexpectedly led her to the material for the stories in the collection, shares her gratitude to her sensitivity readers, and talks about the influence of her long-standing literary relationship with Invisible editor Bryan Ibeas.

Open Book:

What do the stories have in common? Do you see a link between them, either structurally or thematically?

Jessica Westhead:

Avalanche is about the harm done by “well-intentioned” white people (mostly white women) because of unconscious bias, and the polite, quiet kind of racism that isn’t as widely acknowledged as the more obvious forms of racism committed by angry, violent, racist white men whose violent racist actions are clearly wrong—but that does just as much damage behind the scenes. The book also examines how white people continue to centre ourselves and our own comfort in conversations about racism and white supremacy and our role in it, to avoid our feelings of shame about this. I wanted to explore the thought processes behind those behaviours with compassion and humour, and to focus on the humanity of both my white protagonists and the racialized characters who encounter them, without ever trivializing the reality of racism and systemic white supremacy.

OB:

How did you decide what stories to include in the collection? When were they written?

JW:

Before I figured out the theme for Avalanche, I had already written three stories around the time I was working on my last novel, Worry: “Swimming Lesson,” “Mister Elephant,” and “Something Fun to Do on a Beautiful Day.” They all had something to do with the anxiety bound up in being a parent, which was the theme of Worry. Then it occurred to me that, with very few exceptions, I had only ever written about white people in my books. I wanted to be more intentional about this. There was a character in “Something Fun to Do on a Beautiful Day,” about a white mother and father and their only child who fret over the safety of a bird that appears to be drowning in Niagara Falls, who started to change my focus. In that story, the man who sells ice cream to the family is a recent immigrant to Canada, likely a refugee, yet I hadn’t fully defined his identity because the white parents think it would be rude to ask him about his “home country.” That needed more attention. Now my idea for this story was not only to show the constant terror of modern parenthood, but also to contrast the reality of a white family living with privilege (of which they are mostly unaware) with that of someone whose experience of parenthood is much starker because they were forced to flee another country with their child.

While I felt I couldn’t properly do justice to the point of view of the man running the ice-cream cart, I was confident that I could compassionately reveal elements of his situation within the context of the mother and father’s laser focus on their daughter and captivation by the possibly drowning bird, as well as their obliviousness to (and lack of interest in) the circumstances of people with different backgrounds and lived experience. After that, I wrote “A Warm and Lighthearted Feeling,” about a weary middle-aged white mom who develops an obsession with a hijab-wearing fellow subway commuter. Then I continued writing more stories with the theme for the collection taking more shape as I went along. I also “retro-fitted” “Swimming Lesson” and “Mister Elephant” with these new ideas—making those stories as much about quiet racism as they are about parenting. I’m so thankful for the essential feedback and guidance I received from the generous first readers of the manuscript: Jami Heydari, Caroline Habib, Greg Kearney, Kate Barton, Amy Miranda, and Carrianne Leung. They offered much-needed guidance around developing and exploring the themes of Avalanche, and also advised me to avoid portraying any of the racialized characters—including the ice-cream vendor—as tragic figures, but to focus instead on their agency and individuality by hinting at their complex identities outside of the white characters’ gaze.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

How did you decide which story would be the title story of your collection? Why that story in particular?

JW:

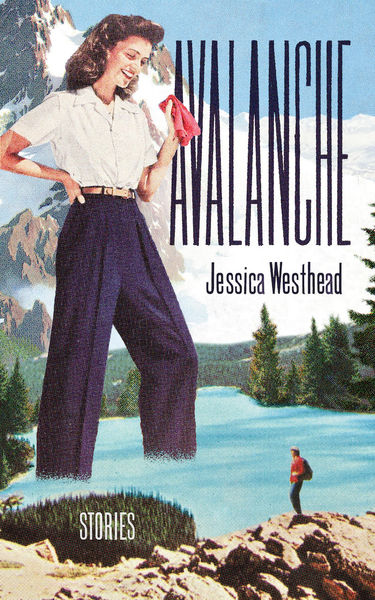

The amazing Bryan Ibeas at Invisible Publishing was my editor, and he chose the title Avalanche. Previously, the title for the collection when I submitted it to him was A Warm and Lighthearted Feeling, and before that, it was Intense Good Times with Other Professionals. “Avalanche” is the title of one of the stories in the collection, and during the editing process, Bryan identified that story as being representative of the whole collection. When he suggested this should be the title for the book, I loved that idea. It just fit. (And the cover that Megan Fildes created in response makes me so happy!) I enjoyed working with Bryan so much—he edited my previous collection Things Not to Do (with Cormorant Books), and he just gets my writing in a really exciting, uncanny way, and helps me make it better.

OB:

Do you think your characters have anything in common with each other, from story to story?

JW:

The white protagonists in Avalanche are all people who either consciously or unconsciously refuse to acknowledge their racism and privilege and the impact of their harmful behaviour, and who focus instead on the goodness of their intentions. My favourite characters to write are people who lack self-awareness because that’s a way for me to create socially awkward situations that are uncomfortably funny. And when it becomes obvious to the reader that a character isn’t aware of how their behaviour affects those around them, my hope is that there’s a heightened sense of awareness on the reader’s part as a result.

Bryan and I also worked together to differentiate the voices in the book—he gave me a “homework assignment” to write backstories for my protagonists, for our reference only. This was so we could separate them—especially the first-person middle-aged-white-lady voices—from, in Bryan’s words, “the Hive Mind of Jessica” (since aspects of my characters are often inspired by the parts of myself I’m most anxious about). And his edits were so beautifully deft and effective. He knows my writing style so well, and in some stories he wanted me to dial up a certain tone, and in others he suggested a few very specific changes (for example, varying my sentence structure or eliminating various narrative tics I’ve developed) to dial it down. I’m also very grateful to sensitivity readers Tamanna Bhasin and Brittany Chung Campbell, who advised me on how I could add subtle, telling details (focusing on body language, for instance) to ensure that the racialized characters were portrayed as fully dimensional, even if they only appeared briefly in some stories.

OB:

Do you have a favourite short story collection that you’ve read? Tell us why it is special to you.

JW:

I have two new favourite collections. The stories in A Dream of a Woman by Casey Plett are funny and sexy and full of so much love. Her prose is just flawless and seamless, with such brilliant dialogue, and I always have this giddy feeling that I’m falling into her words. The scenes are happening all around me and her characters are so incredibly real. There is also this beautiful thread of kindness that runs through Casey’s writing, and these stories overflow with it. In Souvankham Thammavongsa’s How to Pronounce Knife, each story is so polished, each sentence is so sharply crafted, each word is so precise. And all of it is told with a quiet, unmistakable authority in an elegantly careful and matter-of-fact tone, with gorgeously spare prose and a lulling rhythm that carried me along and added even more power to every wry, cutting observation and revelation along the way.

________________________________________________________

Jessica Westhead is the author of the novels Pulpy & Midge (Coach House Books) and Worry (HarperCollins Canada), and the critically acclaimed short story collections And Also Sharks and Things Not to Do (Cormorant Books). And Also Sharks was a Globe & Mail Top 100 Book, one of Kobo’s Best Ebooks of 2011, and a finalist for the Danuta Gleed Short Fiction Prize, and Worry was included on CBC Books’ Best Canadian Fiction of 2019 and the CBC Canada Reads Longlist. Jessica lives in Toronto with her family.