Joanne Robertson and Shirley (Fletcher) Horn Tell the Crucial Story of a Young Girl's Resilience and Survival

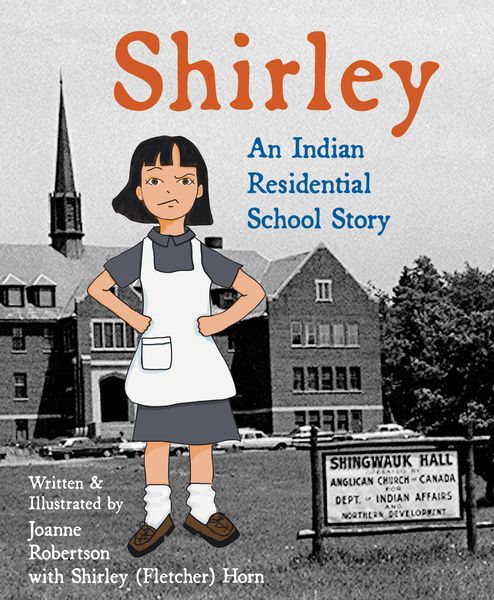

At five years old, Shirley is taken from her family and sent to a residential school, a strange place that she does not understand. The long walk up the school’s stone steps marks the beginning of a life shaped by separation, silence, and strict rules. Her story takes to the page this month in Shirley: An Indian Residential School Story (Second Story Press).

Though Shirley loves to learn, the cost is steep. She is kept apart from her siblings and forced to navigate fear and loneliness on her own. Nights are especially hard, with no one to comfort her, yet she finds ways to endure. She makes friends, notices small moments of joy, and holds tightly to the idea of summer, when she can return home.

Told with clarity and care by author Joanne Robertson, with Shirley (Fletcher) Horn, this true story centres a child’s experience of residential school without softening its impact. It honours Shirley’s courage while reminding readers of the lasting harm of these institutions and the strength required simply to survive them.

We interview the creators of this poignant and essential work of nonfiction for young readers, right here on OB!

Open Book:

How did your memoir project first start? Why was this the right time to tell your story?

Joanne Robertson:

Shirley and I became friends when we were students together at Algoma University. Creating a book about Shirley’s time in the residential schools was suggested by a mutual friend, Joanie McGuffin, who is famous for her gift of bringing people together. She suggested it and made the arrangements for our first interview.

Shirley has done so much work for the people, and her book will now be part of her legacy.

OB:

What do you need in order to write—in terms of space, food, rituals, writing instruments?

JR:

Initially I need a long period of time to mull things over—in this case it was over two years before I wrote or illustrated anything. I always start by laying down sticky notes in storyboard form and then transfer things to a Hibroy exercise book—the half-plain, half-lined version.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

When writing, I wear noise-cancelling headphones with YouTube coffee-shop ambience reels playing. While illustrating this time, I survived on yogurt with bran buds and walnuts, and The Handmaid’s Tale playing on repeat in the background. I use my iPad Pro to write and to illustrate on.

OB:

If you have written in other genres, what was different for you in writing a memoir?

JR:

The Water Walker was my first book, and I was helper to Josephine-ba Mandamin for many years, so I lived parts of that story with her and the water walkers. Shirley’s story was very different for me. I wasn’t with her when these things took place.

I let Shirley look at every draft and every illustration, and I asked her questions as I went. Some illustrations I wanted to be very specific with, because she shared a lot of detail and I wanted to capture those details, either visually or emotionally.

For example, her confirmation dress—I had to redraw it because the sleeves and length were wrong. As a child she worked so hard on that dress, and since she has no photographs of herself wearing it, I wanted to get it right for her. Another example is when her family was in the canoe. She mentioned several times that everyone had a specific place in their father’s canoe, so I wanted to make sure I drew them in their correct seats.

Knowing Shirley for many years, through school and from attending the annual reunions held by the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association, helped me immensely.

OB:

Did you use any materials, documents, interviews, or other research that became part of the writing process?

JR:

After our first interview, one of my first stops was to visit Krista McCracken at the Shingwauk Residential School Centre at Algoma University, where the SIRS archives are held. I went through binders of photographs from the years Shirley attended the school.

At the time, I was trying to answer questions of place—matching rooms and outbuildings to her stories and forming mental images of how I might illustrate them. It wasn’t until a couple of years later that I decided to actually use those photographs as a basis for the illustrations.

OB:

Did you experience any anxiety about making a part of yourself public in this way? If so, how did you cope with the vulnerability of publishing a memoir?

Shirley (Fletcher) Horn:

No, I didn’t. We had already created the Children of Shingwauk Alumni Association, and that’s what we’ve been dealing with since 1980. We’ve done continual research and continual activities with former students. I’ve been talking about my experiences for many years already, so I have no problem sharing them.

JR:

I did have anxiety about sharing Shirley’s story, because I wanted to get it right and not do further harm. Shirley has many humorous stories from her childhood, and with her help I had to find the balance between those moments and the lonely, cruel realities of living in those institutions away from family.

The humour makes her story unique—and even a bit shocking—but it was a challenge to strike that balance. Shirley always reminded me that without those happy moments they created for themselves, she would have perished from loneliness.

OB:

Personal essays, memoirs, and creative nonfiction have become especially popular in recent years. Why do you think readers are drawn to these forms now?

JR:

I wasn’t aware of that, but if I had to guess, I’d say it has something to do with our cell phones and our inability to put them away, even when we’re together in person. It probably has to do with connection—because we’re forgetting how to live in community.

Maybe we’re striving for that connection, for relationships, and these kinds of stories remind us how to go about it. Or maybe we’re living vicariously through others’ stories, with a bit of make-believe thrown in to help it go down easier.

______________________________________

Joanne Robertson is Anishinaabe kwe and a member of Atikameksheng Anishnawbek. She is a graduate of Algoma University and Shingwauk Kinoomaage Gamig. Joanne is the author and illustrator of The Water Walker / Nibi Emosaawdang, Nibi is Water, and Shirley: An Indian Residential School Story. She lives north of Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario.

Shirley (Fletcher) Horn is the first chancellor of Algoma University. Born in Chapleau, Ontario Horn attended the St. John's Indian Residential School (Chapleau, Ontario) and the Shingwauk Indian Residential School (Sault Ste Marie, Ontario). She is well known for her advocacy work relating to the legacy of residential schools in Canada. She is a member of Missanabie Cree First Nation and she served as Missanabie's Chief for six years.