Jody Chan's New Poetry Collection Challenges Systemic Failings in Community Care

Writer and therapist Jody Chan has had plenty of experience with systems of mental health treatment in Canada, and the ongoing shortcomings in care for citizens who are ill and look to these entities for assistance.

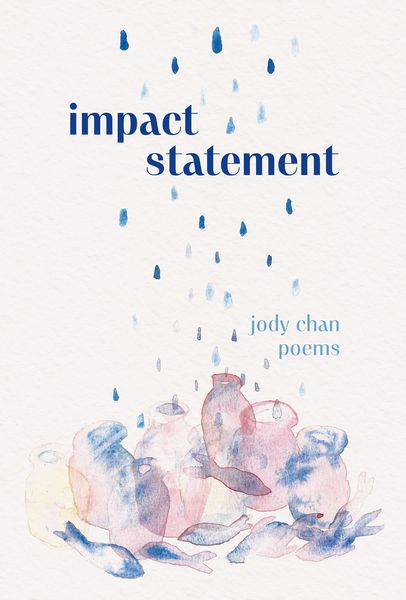

In their new poetry collection, impact statement (Brick Books), Chan uses the forms of patient records, psychiatric assessments, and court documents, to trace a history of psychiatric institutions within a settler colonial state. She explores the many ways that those who are supposed to provide care and service can be part of a corrupted system bent on capitalist gains and keen to punish and neglect the most vulnerable and marginalized in our society.

It is a "revolutionary call to arms," that looks to love, art, and community to counter so-called care in Canada.

Today on Open Book, the author talks about this new poetry collection in a poignant Line and Lyric Interview.

Open Book:

Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your title? If it’s a title of one of the poems, how does that piece fit into the collection? If it’s not a poem title, how does it encapsulate the collection as a whole?

Jody Chan:

“impact statement” is the title of a long poem near the end of the collection, which discusses the serial murders of eight men in the Church and Wellesley neighbourhood, between 2010 and 2017. A victim impact statement, as defined on the Canadian government’s website, is a written document that “describes the physical or emotional harm, property damage or economic loss which the victim of an offence has suffered.” In the context of a colonial legal and carceral system which itself compounds layers of violence and dehumanization, in the context of the uninhibited policing of racialized and queer/trans communities, it offers little justice or relief. How could it, when property damage and economic loss are enumerated on an equal footing with physical and emotional harm? Whose pain is designed— or forced— to fit within the constraints of a blank box; a legal form; a tool for sentencing? “impact statement,” the poem, weaves together many of the anchoring themes of this collection: communal grief, queer world-building, the abolition of prisons and police. Towards an active witnessing, a restless collectivity, an awareness of injustice that compels movement and shared struggle.

OB:

What were you reading while writing this collection?

JC:

Some of the texts whose thinking, whose music underpin this collection include: Health Communism, by Artie Vierkant and Beatrice Adler-Bolton; Disability Incarcerated: Imprisonment and Disability in the United States and Canada, edited by Liat Ben-Moshe, Chris Chapman, and Allison C. Carey; Prison Industrial Complex Explodes, by Mercedes Eng; “Venus in Two Acts,” by Saidiya Hartman; Birthright, by George Abraham; Care Work, by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha; “A Glossary of Haunting,” by Eve Tuck and C. Ree; Remembrance of Patients Past, by Geoffrey Reaume; and Abolitionist Intimacies, by El Jones.

OB:

Who did you dedicate the collection to and why?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

JC:

The collection begins with a content warning, which doubles as a dedication. My editor, Mercedes Eng, and I discussed the ethics of content warnings at length: who they protect, who they excuse. Any content warning is inherently incomplete; and yet, I list a few of the violences that occur within the book’s pages. I wanted to reject the possibility of moves to innocence, or ignorance— “this violence, which has been done in my name, is too difficult for me to look at”— while also inscribing a circle of care around all those who know too intimately what it is to live inside of these oppressive forms. Ultimately, this collection is dedicated to everyone who dares to imagine an otherwise, and who does the work, day by day, brick by brick, of building it.

OB:

Is there an individual, specific speaker in any of these poems (whether yourself or a character)? Tell us a little about the perspective from which the poems are spoken.

JC:

Over the course of writing this collection, a ghost chorus emerged. A first person plural, congregating from the stories of those formerly incarcerated at the Toronto asylum, those murdered by serial killers and state violence, those whose homes and neighbourhoods were seized to become luxury condos and high-end restaurants. I wrote into this slippery “we” not as a project in empathy, or to pretend to speak for anyone other than myself, but to give voice to a collective haunting. Haunting in the sense of Avery Gordon, who writes, in her book Ghostly Matters, “Ghosts are never innocent: the unhallowed dead of the modern project drag in the pathos of their loss and the violence of the force that made them, their sheets and chains.” A density of impact and imagination that intrudes on our present day lives. In tracing the etymology of this ghost chorus, I was haunted, am haunted. My other anchor for these poems was Saidiya Hartman. In “Venus in Two Acts,” she asks, “How does one rewrite the chronicle of a death foretold and anticipated, as a collective biography of dead subjects, as a counter-history of the human, as the practice of freedom? … How does one revisit the scene of subjection without replicating the grammar of violence?” I come to these questions with only more questions. What emerges in the slippage between pronouns? What coalitions, what solidarities? What pluralities of tactic and thought?

OB:

What advice would you give to an emerging or aspiring poet?

JC:

In a conversation with Summer Farah, Samah Fadil, and Priscilla Wathington on Electric Lit, the Palestinian poet and organizer Rasha Abdulhadi writes, “Empire, capitalism, ableism, meritocracy, anti-Blackness, settler colonialism, cisheterosexism, more… all of these coercive ‘norms’ come with their own recruitments and organizing projects, their own orientations and trainings. And their own incentives. There are many rewards for being digestible, a tasty morsel, another commodity for well-established markets. We should never underestimate the capacity of such systems to recycle even our best attributes or hardest held hurts into reasons for us to reinvest ourselves and everyone we love into the mouths of the death machines.” There is not much more to say than that, but again, more questions. How will our poems obstruct the working of the death machines? How might we abolish a literary market that digests our lives into profit and pulp? How will we create a common language against empire— in Palestine, Sudan, the Congo, Haiti, in solidarity with the struggle of colonized peoples everywhere? How will we orient our writing toward life?

___________________________________________________

Jody Chan is a writer, drummer, organizer, and therapist based in Toronto/Tkaronto. They are the author of haunt (Damaged Goods Press), all our futures (PANK), and sick (Black Lawrence Press), winner of the 2018 St. Lawrence Book Award and 2021 Trillium Award for Poetry. They are also a performing member with Raging Asian Womxn Taiko Drummers. They can be found online at https://www.jodychan.com/, and offline at libraries and dog parks.