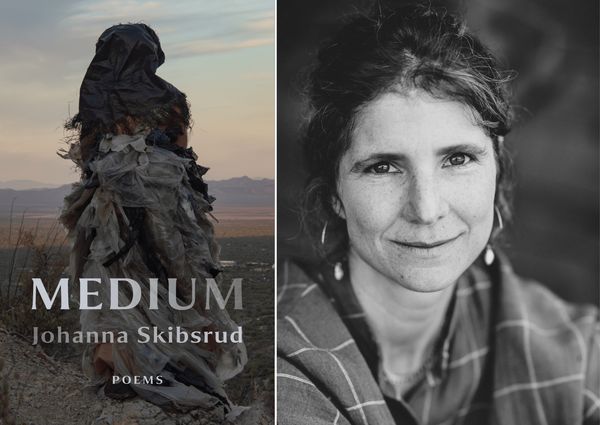

Johanna Skibsrud shares the lives and perspectives of women who biologically, physically, or spiritually shaped the course of history, in Medium

How do we truly transmit experience, while remaining open to transmissions from others; physically, biologically, intellectually, spirituallly, or culturally? This is one of the central questions in the new poetry collection from Giller Prize winner Johanna Skibsrud.

In Medium (Book*hug Press), Skibsrud uses virtuosic poetry to interpret the voices of Helen of Troy, Anne Boleyn, Shakuntala Devi, and others. She challenges the dominant historical narrative of these women, reckoning with the myriad ways that they were silenced and discarded by men, and society.

Each exploration begins with a vignette inspired by the vidas, once used to begin the manuscripts of the troubadours. They are followed by poems that develop different dimensions of the subjects, and that bring the reader into a new understanding about the relationship between past and present, self and other.

Read more about this wonderful collection of poems in this Line and Lyric interview.

Open Book:

Can you tell us a bit about how you chose your title? If it’s a title of one of the poems, how does that piece fit into the collection? If it’s not a poem title, how does it encapsulate the collection as a whole?

Johanna Skibsrud:

I wanted to emphasize the embodied and material aspects of language, text, and subjective experience—as well as the possibility for connection across and through these different mediums. All the individual voices the poems evoke are mediums in some sense—sometimes in a spiritual or intellectual sense (conveyors of wisdom or ideas), other times in a physical or biological sense (conveyors of text or other bodies), and still others in a cultural sense (conveyors of myth and memory). I wanted the collection to celebrate the continuities of experience and knowledge across the apparent and real limitations of space, time and perspective. I also wanted to think about the ways that we transmit experience—and at the same time remain vulnerable and open to transmissions from others.

OB:

Was there any research involved in your writing process for these poems?

JS:

Like the early “vida” forms that inspired them, the short biographies that accompany each poem in this collection are less concerned with historical or narrative detail and more with elaborating the lived dimension of each poetic text. But to develop this dimension I of course had to do a lot of reading about the different women’s lives and legacies included in the book. I explain in the preface to the collection that the vidas of the troubadours “sometimes constrained themselves to a sentence or two — the first describing the poet and the second describing the body of work.” Later vidas, though, developed into what Margarita Egan calls “portrait stories” and tended to blend “literary” and “non-literary” references to the poet’s life. In the vidas I’ve developed, I’ve likewise tried to emphasize the connection between the literary and the non-literary by pointing to the ways that “cultural, historical, and economic forces help to shape the possibility of the projection and reception of a single voice.”

OB:

What was the strangest or most surprising part of the writing process for this collection?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

JS:

For the most part, I’m interested in and fairly accepting of the constraint of language and the page, but this book felt particularly difficult to me in terms of adapting – and feeling satisfied with – its translation into two-dimensions. For me, these poems are voiced and performed, and I confess I have a hard time, still, seeing them in black and white. (Because of this I hope that readers will read them out loud…and really think of them as vehicles—mediums—for their own voices, and those of others.

OB:

Did you write poems individually and begin assembling this collection from stand-alone pieces, or did you write with a view to putting together a collection from the beginning?

JS:

The book began with the first poem, “The Sybil Speaks,” which describes the voice as “an opening, a door—” and, I don’t know. Something really did open up for me with that poem. There seemed to be so many more voices, and so more poems followed. And once I’d conceived of the structure and format for the collection as a whole, the possibilities of who might be included—the dimensions of feminist history and experience the book might, or could, hold—were endless, and so a major constraint of this collection (in addition to, and beyond the page) was chance, and my own personal experience: the different histories, ideas, and voices that happened to cross my path. Instead of thinking of these chance-based decisions (about what to include and what not to) as hard limits—or of having had, eventually, to say “that’s enough” and finding a place to stop, I’d like to think of the poems that did get written—then edited and compiled in this collection—as a sort of preamble, or rather an excerpt, from a much longer evocation of ancestral voices that’s been going on, in some form—and will continue to go on, with any luck—forever.

OB:

What's more important in your opinion: the way a poem opens or the way it ends?

JS:

I like to think that the opening and the ending of a poem are related – they’re both so important because they’re the connective point to what (harking back to my response to the last question) exists beyond the poem, but is very much a part of it, nevertheless. You have to try to get both the beginning and the end just right, I think, in order that the reader can get a sense of that other place—wherever it is that the poem is coming from and disappearing to.

OB:

What were you reading while writing this collection?

JS:

So many different things, because the writing of the collection took over ten years. Most instructive for the book, of course, were the writings by, or about, the individual women whose stories the poems evoke. I’d like to think, though, that just as influential were the countless picture books and nursery rhymes and children’s fantasy tales I’ve read over the past decade—because the writing of this book corresponded exactly with the early childhoods of both of my kids. The cadences and rhythms of children’s stories, rhymes and song are probably our most ancient form of magic. Then there’s the portals to other, alternative worlds and bodies, imagined by so many classic fantasy series, like The Dark is Rising and The Chronicles of Narnia….I like to think that a little of that magic got into this book. Also, at a certain point, early on in the life of these poems, I began to explore the voice of Joan of Arc, and then of her mother. These two don’t show up in Medium, but are the subject of another project I’m working on now—a novel in two parts. So, alongside the reading I’ve been doing for this project, I’ve been reading a lot on female mysticism in the middle ages, xenoglossia, and histories of female authorship and power. I’m sure this reading has informed at least several individual poems, as well as the project as a whole.

OB:

Who did you dedicate the collection to and why?

JS:

I dedicated this book to three different, very powerful women in my life—women I’ve come from, and whose stories and voices have become a part of me. My mom—Janet Shively—and my two aunts, Ellen and Peggy, taught me how to pay attention and to celebrate the world around me. They also taught me how to love stories, and to listen them, and tell my own. We lost my Aunt Ellen in December, which makes the launch of this book bittersweet. I wish so much I’d been able to share the book with her—and let her know that it was dedicated to her. I’m trying to be true to her spirit, and to the spirit of the collection, by having faith that the borders are more porous than they seem. I’ve also dedicated the book to my sister, Kristin, and to both of my kids, because I wanted to acknowledge how we—the different generations—overlay, and to a certain extent even become one another; how we continue to exist with and through one another somehow.

__________________________________________________

Johanna Skibsrud is the author of three previous collections of poetry, three novels—including the Scotiabank Giller Prize–winning novel, The Sentimentalists—and three nonfiction titles, including The Nothing That Is: Essays on Art, Literature, and Being, and most recently, Fool: A Study in Literature and Practice. An Associate Professor of English Literature at the University of Arizona, Johanna divides her time between Tucson, Arizona, and Cape Breton, Nova Scotia.