Jonathan Garfinkel on Exploring the Legacy and Traumas of the Soviet Union in His Incendiary First Novel

Jonathan Garfinkel is known for his riveting nonfiction, including his celebrated memoir Ambivalence: Crossing the Israel/Palestine Divide, and his work in poetry and playwriting, which have earned him critical acclaim and even a Governor General's Literary Award (for his play House of Many Tongues).

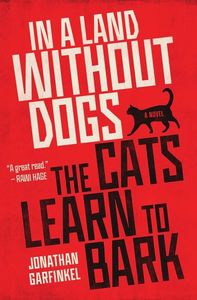

His newest work, however, has taken him in a different direction, with the publication of his first novel, the wickedly dark, funny, offbeat In a Land without Dogs the Cats Learn to Bark (House of Anansi Press).

As cheeky and ambitious as its title suggests, the novel is expansive, encompassing multiple generations and locations, as it follows a former Soviet nation struggling to find and assert its own identity, culture, and legacy. The country's progress is mirrored in the lives of Garfinkel's eclectic cast of spies, artists, politicians, and regular folk caught up in a mystery that keeps the pages briskly turning and which will keep readers guessing. A perfection refutation to anyone still beating the old "CanLit is dull" drum, In a Land without Dogs the Cats Learn to Bark is a wild, complex, supremely readable debut and a timely look at the ever-lurking threat of Russian dominance.

We got to speak with Garfinkel about the novel and its international roots. He told us about his time in Georgia, and how the country, while partially a palimpsest of its occupiers over the years, retains its own vibrant identity, particularly in the world of theatre and other arts, and how its progress inspired his writing. He tells us as well about how his Jewish heritage helped him find connection in post-Soviet countries, and about how a surreal and impromptu hunting trip with strangers made its way into the book.

Open Book:

Do you remember how your first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Jonathan Garfinkel:

Twenty years ago, I was in a small mountain village in the north of the Republic of Georgia, 10 km from Chechen border. I was supposed to be there for 24 hours – a day off from the theatre I worked at. I got drunk with two of the locals and woke up the next day with a horrible hangover and three feet of fresh snow outside my window. I was stuck in this village called “Kazbegi” for eight days. Geographically it is located in a fascinating confluence of north and south, east and west. The Georgian Military Highway brings in people from Moscow, Yerevan, Tehran, and even Turkey. Chechens, Georgians, Daghestanis, Circassians, Russians, Georgians, Greeks, Turks, Armenians, Azeris... They all passed through during my time in this village. I learned the mythology of the place; Mount Kazbek was where Prometheus had been chained to a mountain for eternity for stealing fire from the gods. It was also where Lermontov had situated part of A Hero in Our Time. I knew this place was special; I didn’t know how to write about it. I kept a diary that became the seeds for this novel.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

JG:

The setting was all I had at the beginning of writing. I knew I wanted to write about Georgia, but how? But first, why Georgia? For this I need to thank Toronto theatre director Paul Thomspon, for without him I’d have never even heard of the place. Paul was my mentor when I was a young writer. He is also one of the pioneers of Canadian theatre who made seminal theatre like The Farm Show and 1837. Paul led me on a mad 48 hour bus from Istanbul to Tbilisi; it’s a journey I’ll never forget. When we arrived in Georgia, we set ourselves the task to explore the burgeoning theatre scene; we had something to learn. From the moment I arrived, I was utterly seduced by the former Soviet republic. In the early 2000s, it was a fascinating place, a sort of lawless country that called itself a democracy but in reality was run by former Communist thugs, as well as gangs of thieves and bandits. Corruption was rampant – I had to bribe my way to get into the country the first two times I arrived. There was also rarely electricity, running water, or heat. In spite of the chaos, there was an incredible art, theatre, and electronic music scene. People not only endured the difficult times but banded together in interesting ways. I was lucky to be there in 2002 and 2003 to work on a theatre project with one of the local theatres, “Sardape”, and to collaborate with the artistic director Levan Tsuladze. I also had the privilege to experience firsthand the innovative spirit of the country.

During this time Georgia was changing politically; the pro-democracy “Kmara” movement – a network of NGOs that blossomed into the “Rose Revolution” of 2003 – led a non-violent revolution from its youth. I was fascinated by these political changes; about the anxiety of influence by American NGOs countered by the pull of the old Russian and Communist empire; all the while young people just wanted to live in a freer, more open society. I witnessed Georgians oust the former Communists, put a Western-leaning leader in their place (Mikheil Saakashvili). I saw them reform the police force, the border patrol, and even gentrify the old city of Tbilisi. And let’s not forget cheap European airlines that brought in the tourists! Things changed over the years, the edge perhaps wore off, but I was always drawn back to the Georgia; wowed by the generosity of the people; the mythical and immense geography and history and linguistic complexity; blown away by their theatre which seemed somehow embedded in people’s souls; and utterly entranced by a culture that was influenced by its previous occupiers Russia, Persia, Ottoman, but retained its own vital sense of identity and language. Over the years, I went back many times, continued enduring friendships, fell in love, had adventures. In a way, the novel is a kind of love song to this country.

OB:

Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

JG:

It took me a long time to find the story. A love song is all fine and good, but it doesn’t equal characters, story or structure. Also, because I wasn’t from Georgia, I needed to find my own connection to the place, other than an “I love it” exoticism. While I was born in Toronto, my Jewish grandparents came from Western Ukraine; I always felt a pull to former Soviet countries. As an adult writer, I lived many places, including Lithuania, Poland, and Hungary, in part because it was cheap (I currently live in Berlin). I think it’s important to leave the comfort of home. Yet I was in Eastern Europe for other reasons, reasons of ancestry and history. At first, I came to touch a ghostly past (the massacre of the Jews of Europe) – to try and reckon with those ghosts. But what I found was a vibrant present where poets and artists are celebrated in ways we don’t see in North America. All to say, these are good places to write and meet other artists while being part of something larger than oneself. So I spent a lot of time in former Soviet countries like Ukraine, Azerbaijan, and Georgia, immersed in the past, discovering the present, while we all looked toward an uncertain future. Russia was always lurking over our shoulders.

I guess you could say my way into the novel became an exploration of the legacy and traumas of the Soviet Union. It’s been a lifelong obsession of mine. What we call the “post-Soviet”. That’s how I found a personal stake in the book. I also wanted to give voice to the many inspiring people I met along the way. So yes, the novel’s ending changed many times, radically from draft to draft – I don’t want to give away the ending, not even the false ones. Most importantly, the structure of the novel changed. At year five in the writing process, with the consensus of my editors at Anansi, I shattered the one-story protagonist structure, and ended up telling it from three perspectives, from three different countries in three different time periods. The rewrite took two years. It also freed up the language in a way I could never have predicted – it became a completely different book. I don’t know how else to explain it; something that had been missing, suddenly came alive. During the pandemic, I rewrote about 75 percent of the book, including the ending, at least five times.

OB:

Did you find yourself having a "favourite" amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

JG:

Daniel Daniel was easily the most fun and joyous to write. I could see him so clearly, hear him too. I love his idiosyncracies and his intelligence and the way he plays with our cliches of Eastern Europe and the post-Communist world. And the fact he owns a record store specializing in jazz. I listened to a lot of jazz while writing this.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

JG:

The research was immense. I read everything, which, to be honest, isn’t a lot in the English language. But I read whatever there is. I watched Georgian films and theatre and studied its literature. I went back to Georgia many times, always for long periods, never less than two months at a time. I interviewed people who were integral to the Rose Revolution; I interviewed former Soviet dissidents; I met with artists, photographers, musicians. The Georgian performance artist, Nino Sekhniashvili, inspired the character of Tamar – Nino once robbed a bank and used the security tape footage as her performance video – this is in my novel. I also traveled to an infamously dangerous part of the country, Pankisi Gorge, a Chechen enclave where many suspected Chechen boyevikis were hiding out from Russia. I interviewed people everywhere and tried my best to absorb the landscape, to understand it by feeling, smell, and sound. I even went on an impromptu hunting trip with a poet and an entrepreneur whom I had met one morning at a café. When they invited me hunting, I thought they were joking – it was 11 am – the next thing I knew we filled their SUV with ammunition and wine. Quickly realizing I was perhaps getting in too deep, but too polite to say, “let me go,” I was taken to a remote forest hours outside of Tbilisi. Here I was given a Kalashnikov and told to kill wild game. I had never hunted before—never even held a gun—and while I was a little drunk, they did teach me how to fire that very heavy and old weapon. Needless to say, I didn’t kill anything, but we ended up having a great lunch by the Sioni Reservoir. An adaptation of that scene made it into the novel.

OB:

Did you celebrate finishing your final draft or any other milestones during the writing process? If so, how?

JG:

Yes, but I always celebrated too soon: I can’t tell you how many times I thought I was “done”. In the end, it was the deadline that took the book away from me, and even then, there was the copy edit, then another copy edit and then... I felt I was always celebrating “finishing”, so that by the time it really was out of my hands, I didn’t feel much like it.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

JG:

I dedicated the novel to Toronto theatre director Paul Thompson, who first took me to Georgia in 2002. And to an actress and artist I met and fell in love with in Tbilisi, Ana Aphkhazava, who died tragically in a car accident at the age of 33. ____________________________________________

Jonathan Garfinkel is an award-winning author. His plays include Cockroach (adapted from the novel by Rawi Hage) and House of Many Tongues, nominated for the Governor General’s Literary Award for Drama. The controversial The Trials of John Demjanjuk: A Holocaust Cabaret has been performed across Canada, Russia, Ukraine, and Germany. He is the author of the poetry collection Glass Psalms and the chapbook Bociany. His memoir, Ambivalence: Crossing the Israel/Palestine Divide, has been published in numerous countries to wide critical acclaim, and his long-form nonfiction has appeared in the Walrus, Tablet, the Globe and Mail, and PEN International, as well as Cabin Fever: An Anthology of the Best New Canadian Non-Fiction. Named by the Toronto Star as “one to watch,” Garfinkel is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in the field of Medical and Health Humanities at the University of Alberta, where he is writing a memoir about life with type 1 diabetes and the revolutionary open-source Loop artificial pancreas system. He lives in Berlin and Toronto.