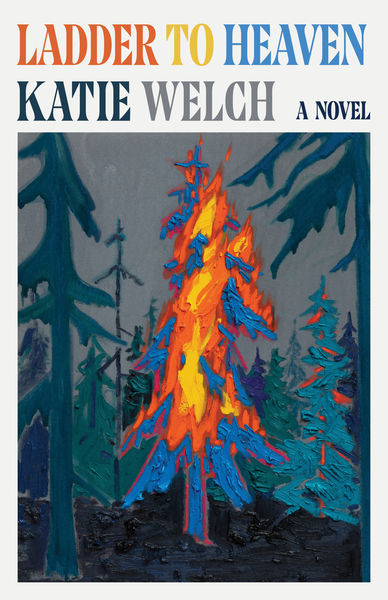

Katie Welch Explores How We Rise from the Ashes in the New Novel, LADDER TO HEAVEN

In Ladder to Heaven, acclaimed author Katie Welch takes readers into a wondrous and perilous near future. The year is 2045, and an earthquake has shattered the Pacific Coast, upending not only cities and lives but the very nature of communication. In this strange new world, humans and animals can finally understand one another, a gift that arrives in the midst of climate catastrophe and deep uncertainty. Welch weaves a story that is speculative and achingly human, filled with heart, loss, and the glimmer of redemption.

At the centre of this transformed landscape is Del Samara, a woman struggling to rebuild after losing nearly everything. Battling addiction and grief, Del abandons her daughters to seek solitude at her father’s fishing cabin, accompanied only by her loyal dog, Manx. When she finally steps back into the world three years later, she discovers that society has evolved into something unrecognizable, reshaped by disaster and revelation alike. Her journey toward Vancouver Island becomes both a physical odyssey and a profound search for forgiveness, connection, and peace.

Written with lyricism and compassion, Ladder to Heaven explores what it means to survive, to listen, and to heal in a changed world. Welch’s storytelling shines with empathy and imagination, revealing the fragile beauty of interaction across species and the unbreakable bonds of family. This is a haunting, hopeful novel about what remains when the very fabric of the earth has changed.

We've got an enthralling Long Story Novelist Interview with the author to share today, so read on!

Open Book:

Do you remember how you first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Katie Welch:

Ladder to Heaven began as a short story called “Hukka and the Cougar.” I had recently ended my marriage and gotten sober. Fear that I had permanently alienated my daughters, then teenagers, combined with a swelling sense of the climate crisis; Trans Mountain Expansion oil pipeline construction had begun in my community, and following an Extinction Rebellion–style protest that I had organized, I was receiving hate mail.

I channelled the jittery energy of these challenges into a protagonist, Del. In the story, Del retreats from her problems to live in the wilderness. Withdrawing from drugs, she communicates telepathically with animals, and a cougar comes to her rescue when she is set upon by strangers. The finished story was published in Issue 15 of The Temz Review in 2021.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

KW:

In my early twenties, I planted trees, travelling extensively in British Columbia before settling in the interior. I love the province’s coastal regions, and during the pandemic, my husband and I built an off-grid dwelling on a Gulf Island.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The novel’s action revolves around an earthquake caused by the Juan de Fuca tectonic plate subducting beneath the continental plate in the Pacific Northwest—a drastic geographic and societal event that triggers language barriers to dissolve. I imagined Del’s hermitage in the interior, and this led to the idea of an overland journey in an unexpected direction, away from inland safety, toward maritime communities devastated by the earthquake. This journey allowed me to set the action in two different, beautiful ecospheres, and to describe the transition between them, mirroring my own transition from the interior to the coast.

OB:

Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

KW:

Del develops an existential crisis, and I was not certain, as I wrote, how this crisis would resolve. Even when I came to the final scene, I couldn’t decide which conclusion would be the most satisfying and authentic. I wrote two very different endings and chose the one that felt right.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about the process.

KW:

“The Really Big One,” Kathryn Schulz’s 2015 prizewinning piece for The New Yorker, was a major inspiration for Ladder to Heaven. Schulz’s essay is comprehensive, but I wanted more specific detail about what an earthquake in the Pacific Northwest would look like. Cascadia’s Fault: The Coming Earthquake and Tsunami That Could Devastate North America (Jerry Thompson, 2011) was my primary source for likely damage from a large seismic event in this area, including planned emergency response (and lack thereof).

Thompson’s book was important, but the information—a white settler perspective—felt lopsided. In “The Really Big One,” Schulz explains that Indigenous people understood the seismic risk of their homes. In art—stories and images—the First Nations of the Pacific Northwest issued warnings that large earthquakes were possible. Searching for Indigenous knowledge on the topic led me to Ann Finkbeiner’s 2015 article in Hakai Magazine, “The Great Quake and The Great Drowning,” which informed many of the novel’s descriptions.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

KW:

In November 2021, I was writing about a horseback journey over the Coquihalla Highway, a mountain pass destroyed by the earthquake. I imagined asphalt plates sliding into ravines, chunks of road carried away by mudslides, rubble burying lanes, and water coursing where cars had once driven.

On November 14, an atmospheric river—a storm intensified by climate change—swept across the region and devastated the Coquihalla. The damage was compounded by wildfire- and deforestation-destabilized soil. Amazed and horrified, I watched drone videos of destruction I had just imagined. It was a flood, not an earthquake, but the highway was rendered impassable by a natural disaster, and even today, the uncanny timing raises hairs on the back of my neck.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

KW:

Ladder to Heaven is dedicated to my daughters, Olivia and Heather, and to my (second) husband, Will. Visceral terror of having abandoned my children fueled Del’s fictional abandonment of hers. I composed the novel balanced between hope and despair, unsure how my relationship with my daughters could or would move forward.

Olivia and Heather’s faith and love sustained me as I wrote, and the healing between us informed the novel’s resolution. Will encourages and wholly supports my writing endeavours with profound patience, wit, kindness, and thoughtfulness.

OB:

Did you include an epigraph in your book? If so, how did you choose it and how does it relate to the narrative?

KW:

The novel has three short epigraphs. The first, an eight-word poem by Ted Poole, includes the novel’s title: the ladder to heaven has only one rung. Handwritten on a slip of paper inside a carved wooden box, the poem was a wedding present—a beautiful expression of unconditional love. Del’s inward journey is toward self-love.

The second epigraph is from Dutch philosopher and animal rights activist Eva Meijer: “People say animals cannot speak. Of course they speak. They speak to us all the time. The only thing is that we don’t really listen.” It’s clear to Meijer, and increasingly to us all, that animals communicate. I wrote the animal voices in Ladder to Heaven on instinct and was surprised how convincing they were: a fish out of water protests its murder; dogs rejoice when they are walked; coyotes band together to pursue mischief. I believe Nature has wisdom that far surpasses human intelligence. We would do well to respect this wisdom; our survival may depend upon it.

The final epigraph is from a song written by BC musician Sam Tudor: Clinical names are taking all my friends away. It becomes clear to Del that she and her youngest daughter, Cleo, are psychologically different from their peers. I resisted diagnosing these characters; the labels we apply to those who don’t occupy a middle ground are frequently unhelpful and alienating. I wanted the reader to accept Del’s difference without pigeonholing her according to her foibles.

OB:

What, if anything, did you learn from writing this novel?

KW:

I always admired and believed in Ted Poole’s small poem, but as the novel progressed, the importance and rewards of a philosophy centralizing love became truer and more tangible. Even as the world seemed to shift in another direction, love loomed larger in my mind and heart. “The ladder to heaven has only one rung.”

___________________________________________

Katie Welch writes fiction and teaches music in Kamloops, BC, on the traditional, unceded territory of the Secwepemc people. Her short stories have been published in EVENT Magazine, Prairie Fire, The Antigonish Review, The Temz Review, The Quarantine Review and elsewhere. She was first runner-up in UBCO’s 2019 Short Story Contest, and her story “Poisoned Apple” was chosen as Pick-of-the-Week by Longform Fiction. Katie holds a BA in English Literature from the University of Toronto (1990). Her daughters, Olivia and Heather Saya, share her passion for nature and outdoor recreation. Katie loves to cycle, hike and cross-country ski with her husband, Will Stinson, and they are creating a remote home on Cortes Island, in Desolation Sound.