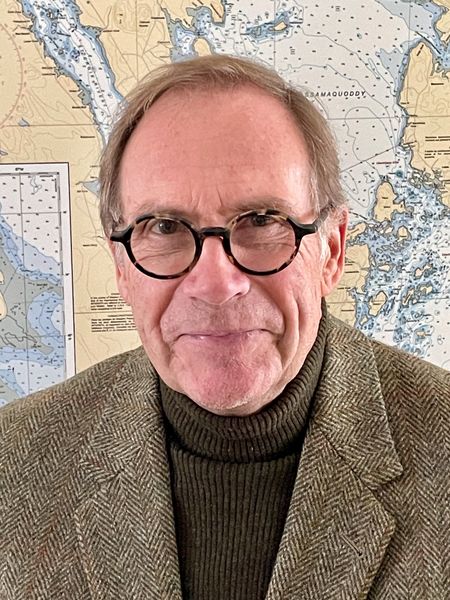

Mark Blagrave Takes the Reader on a Journey, and Questions Truth and Memory in His New Novel, Felt

Veteran novelist Mark Blagrave is back with another new work, and one that uses elements of his lived experiences to anchor a personal, heartfelt story.

In his latest novel, Felt (Cormorant), we follow museum curator Matthew Reade, who finds his career and marriage in tatters after a recent exhibition. In the middle of that tumult, he receives a call about his elderly mother, who has been diagnosed with Alzheimer's. Under the cover of a supposed research project, he returns to the Maritimes to see her and assess the situation.

All of this leads to threads pulled and secrets from his mother's past revealed piece by piece, from her emigration from Norway to New Brunswick to her complicated past relationships. Reade tries to sift through it all and parse out the truth, wondering what he can trust to be real.

We've got a very interesting Long Story Novelist Interview with the author to share with you today on Open Book, where the author talks about the origins of the novel and how he drew from his own experiences to bring the story to life.

Open Book:

Do you remember how you first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Mark Blagrave:

I had recently quit my job, moved about a thousand miles, and was finishing up a draft of my third book, so I was already in a state of mixed exhilaration and terror. Why not add to all that uncertainty and risk by starting a new novel too? The job change (essentially from having one to not) and the change of place (back to New Brunswick where I wasn’t born but had lived most of my life) had got me thinking about the stories we tell ourselves about our pasts and how we got to where we find ourselves. At almost the same time as I moved, my ninety-three-year-old mother received a definitive diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, which meant that trying to understand and negotiate the ways in which memory works (and doesn’t) became a daily thing. Working on Felt helped me with that.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

MB:

Settings have always featured highly in my writing. Sometimes (I hope) they almost become characters in their own right. The under-sung city of Saint John, New Brunswick, fed both my novels Silver Salts and Lay Figures, and many of the stories in the linked collection Salt in the Wounds are stickily embedded in sites I visited with family in Germany and Austria. My current home of St. Andrews-by-the-Sea was still relatively new to me when I embarked on Felt and I was eagerly absorbing every bit of it I could. That meant not only wandering and exploring the handsome streets and gorgeous shoreline but also doing lots of reading about the history. An excellent book on Ministers Island (the summer estate of Sir William Van Horne) led me to the story of a failed state-of-the-art sardine-packing factory. Along with that, a delightful history of the local Cottage Craft business, got me going on the string of “what-ifs” that I always need to provide the seeds for a novel, and so to the creation of Thora, the gutsy matriarch Norwegian sardine packer who founds a craft empire in conservative St. Andrews around the end of the First World War. Thora, and her daughter Penelope, and Penelope’s son Matt are all very much, in their own distinctive ways, creatures of the novel’s setting. Their history and their geography are practically one and the same. In a book about remembering, which Felt is, setting becomes all the more crucial because of the powerful links between place and memory.

OB:

Did you find yourself having a “favourite” amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

MB:

I think the diplomatic answer to that question is that “I love all my children equally.” But I do love my characters differently, and not all the time. The telling of most of the book is divided between Penelope’s experience on the one hand and the experience of her son Matt on the other, and whichever one I am with at any given point I begin to think is my favourite. Penelope, though, has been given the more interesting life story and was by far the most rewarding to work on because of the challenges presented for me in trying to enter her world as she loses her grip on parts of it and manufactures alternative versions to carry her through. She is modeled (however inadequately) on several smart, funny, independent older women I have known and admired over the years, and I hope that they would (if they could) still sit down and have a drink with me—even after reading the book.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

MB:

Reading historical works about the St. Andrews area was a first step. I wanted to write something that was recognizably rooted not only in the geography and topography but in historical facts—but not quite a historical novel (though it dips backwards into the characters’ pasts, which takes us over a hundred years into the past.) Instead, I was aiming for a kind of alternative history based on “what-ifs.” What if, rather than the way things are recorded as having happened, one or two elements were changed and the whole thing came out just a bit differently? That approach afforded me a very liberating relationship with my historical sources and meant I could veer from them with reckless abandon when it suited me, which is not that far off from what we all do as we embroider and curate our personal memories.

I did quite a lot of reading about memory and specifically about Alzheimer’s, and about memory in art, and about the Art of Memory as practised by the Ancients and the Middle Ages and Renaissance, and even today in “Memory Olympics.” Pulling all of these far-flung threads together into the fabric of a piece of fiction was itself also a way of exploring the workings of memory and the process of confabulation.

And then there was the on-the-ground research into nursing homes and the experience of living with Alzheimer’s which created its own memories of all emotional stripes from despondence to (yes) joy. Think of one of those Chekhov stage directions: “laughingly through tears” and you get the idea.

OB:

Did you include an epigraph in your book? If so, how did you choose it and how does it relate to the narrative?

MB:

Felt has no fewer than three epigraphs. That’s not (entirely) because I couldn’t make up my mind. Two are from works that are “non-fiction” and one from a piece of fiction, and their authors represent a broad range of historical periods. A passage from Quintilian about the importance of place in forming and retaining memories and one from Robert Macfarlane’s The Old Ways about how history issues from geography both speak to the importance of setting in the book and are joined by Virginia Woolf’s well-known passage from Orlando about memory’s needle with its unpredictable series of stitches. I hope that mix of periods and genres and ideas tunes the reader up reasonably well for the experience of the novel that follows.

____________________________________________

Mark Blagrave was born and raised in Ontario, and has lived in New Brunswick most of his life. His first novel, Silver Salts, was shortlisted for the 2009 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best First Novel and his novel Lay Figures was longlisted for the Dublin Literary Award. He now lives in St. Andrews, New Brunswick.