Michaela Jeffery's The Extractionist is a Razor-Sharp, Neon-Noir Thriller

Calgary-based playwright Michaela Jeffery has been winning accolades and awards for her work for some time now, and has been exciting audiences with her stunning works that lean into themes of feminist justice and pushing back against the powers-that-be.

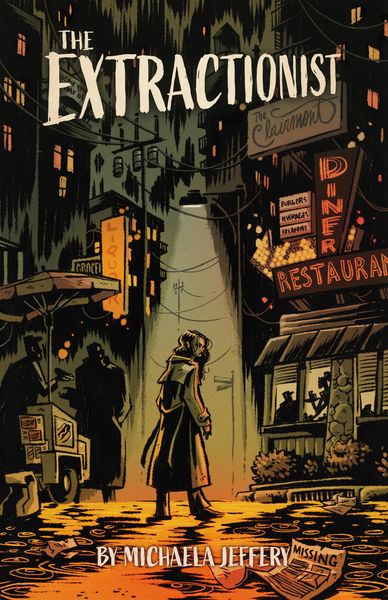

In her latest published work, The Extractionist (Playwrights Canada Press), we enter a neon-noir world where a young woman goes missing, and deprogrammer Asha Ray is called in to track her down. This formidable protagonist, who specializes in extracting at-risk people from the clutches of dangerous cults, links up with retired detective Reuben Medina to find the missing woman before it is too late. But, as they dig deeper into the mystery, they find themselves up against vast corruption and the wiles of a particularly powerful predator.

The story is a harrowing crime drama with an unforgettable central character at its heart, and were thrilled (literally) to share this Behind the Curtain Playwrights Interview with the author!

Open Book:

How did this play first come to life for you? Do you remember the first bit of writing you did for it?

Michaela Jeffery:

Generally, I’ll sit a long time with a story before I start writing. I’ll sometimes spend years collecting articles and doing preliminary research before I feel I’ve really got a handle on what a play is truly ‘about’. Most often I’ll start at the outer edges, with the larger world of the piece, then I’ll build out the characters who inhabit it before eventually making real ‘writing’ decisions about how the story itself unfolds. The Extractionist was a departure for me. Because it began with a pitch document – a distilled and focused summary of what the play was going to be and what it was going to feel like – my process for approaching it was (pleasurably, as it turns out) more mercenary. I was working from the inside out. I knew whose story I was telling and how I wanted to find my way through it before I had many of the world details or supporting infrastructure in place, which felt a bit like tightrope walking without a net at times, but I think made for a sense of movement through the piece that I hope is really satisfying.

The first scene I wrote was the interrogation scene between Beechum and Asha at the top of the second act. To me, that exchange contains many of the story’s fundamentally unresolvable questions, embodied by two tough and principled people at an impasse, conflicted as to what, in that moment, would be a just outcome?

OB:

Was there a question you were exploring in this work, and if so, did you know what it was when you started writing?

MJ:

In a society where the forces of law and order are intrinsically tied to privilege and power, what is the cost of justice and to what lengths would it be reasonable to go in its pursuit?

I’ve sometimes talked about this play as a ‘vigilante thriller’ or a ‘revenge fantasy’ – neither of which feels to me like a complete descriptor on their own. I wanted to write a character and a world that would feel familiar to us (an old-school Noir) – until it isn’t. That feels morally uncomplicated – until it’s not. Asha is a challenging protagonist whose actions are unquestionably divisive. She steps out of bounds frequently and with relish. As a habitual rule follower, there was something deeply attractive to me about a character who was at peace with angering or disappointing people, who would act in accordance with her conscience regardless of the law of the land. Because what do we owe ‘the law of the land’ when it conspicuously shields those that can afford to buy its protection and systematically victimizes those who cannot? I think it’s a complicated, uncomfortable question for most of us, which makes it a necessary and urgent thing to explore on stage.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What drew you to the setting of your play and how did you go about creating it?

MJ:

The Extractionist is set in an unspecified urban metropolis. I wanted to create a sort of ‘Gotham City’ – similar enough to a real-world city like LA, Tokyo, or New York, but abstracted enough that it doesn’t become an indictment of any one place or give any of us the ‘out’ of believing ‘that wouldn’t happen here.’ The early drafts of the script gave a suggestion of the feel of the setting, but the real world-building happened in collaboration with the incredible design team on the original Vertigo production. Set and lighting designer Andy Moro created and entirely projection-based set design that fully captured and developed upon the sense of a giant living and breathing city. Because so much of the story lives in the movement between locations, a design that would emphasize rather than diminish the overlaps and transitions played a critical role in shaping the cinematic sense of how the play reads in the published script.

OB:

In your opinion, how does one go about writing great and memorable characters for the stage?

MJ:

I think that the greatest characters in theatre are the ones that seduce us into confronting ourselves about something in us we’d rather not look at too closely. I think those characters that get under our skin live with us a lot longer than those we simply love or hate.

I don’t think this necessarily even needs to mean morally gray characters or villains. I think there’s a lot of dramatic power in watching a virtuous or well-meaning character dig in and make progressively more and more harmful and destructive decisions as a result of their own moral inflexibility, or a character so desperate for love and approval they slowly give away their power, or a character who knows their course but struggles for five acts to summon the resolve to act on it.

It feels a little reductive to say ‘humanity’, but I really do think that’s it – characters tangled up by their own humanity are easily the most interesting, affecting, and memorable.

OB:

Do you feel your work has changed in any way through your writing life and career? If so, how?

MJ:

I think I write now with a greater respect for joy than I had in my early writing life. I operated with a high level of control in all things. I always wanted to know where a story was going before it got there. I didn’t make a lot of space for curiosity, and I know my earliest writing suffered as a result. I didn’t give it an ounce of space to develop into something that might surprise me. I didn’t leave any loose ends – which, I would eventually realize, meant I closed a lot of doors prematurely in the interest of feeding my own personal fiction that I fully and completely knew what I was doing. I took very few creative risks.

Over the years I would say that I’ve tried to learn to extend myself more trust – to write from a place of pleasure and enjoyment and uncertainty.

_____________________________________

Michaela Jeffery is an award-winning Calgary-based playwright and graduate of the National Theatre School of Canada. Selected writing credits include The Extractionist, WROL (Without Rule of Law), Wolf on the Ringstrasse, The Listening Room, Godhead, and Always. She has been a finalist for ATHE’s Jane Chambers Playwriting Award for excellence in feminist theatre, the Alberta Playwrights’ Network’s Alberta Playwriting Competition, and the Playwrights Guild of Canada’s RBC Emerging Playwright Award.