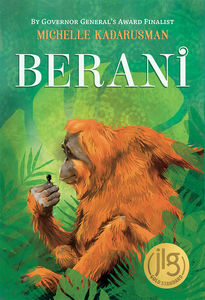

Michelle Kadarusman Brings Together Threatened Orangutans, Palm Oil Controversy, and Passionate Young Activists in Her New Novel

Humans and orangutans share 97% of our DNA, yet we have pushed these highly intelligent animals to the point of being endangered through habitat loss and human encroachment.

Governor General's Literary Award-nominated children's writer Michelle Kadarusman brings her passion for the great apes to the page in her moving new middle grade novel Berani (Pajama Press), which follows three young characters in Indonesia: Malia, passionate and determined to use her privilege for good; Ari, scrapping by and glad to just be able to go to school but still troubled by the environmental inequality he sees; and Ginger Juice, an orangutan owned by Ari's uncle, who is trapped in a small cage and whose rainforest home has been transformed into a palm oil plantation.

A book about bravery and doing what's right, standing up for the voiceless, and what we owe one another, Berani is a powerful, bittersweet, and engrossing story that can help blow the spark of environmentalism in young readers into a flame. We're excited to speak with Michelle about it today as part of our Long Story novel interview series.

She tells us about the real life orangutan who inspired Ginger Juice (and shares a thankfully happy ending to that story), talks about the uncomfortable role palm oil now plays in the home habitats of orangutans, and tells us why she loves writing for "idealistic and impassioned" middle grade readers.

Open Book:

Do you remember how your first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Michelle Kadarusman:

I’ve been carrying around the kernel of this story for almost thirty years. At the time, I was living in Indonesia (my father’s homeland) in a city called Surabaya in East Java. My brother was also living in Indonesia and he was working in the nearby town of Malang. He called me after he’d been to a small restaurant, a warung, that had an orangutan in a cage as an attraction. We were both upset and wondered what we could do. It’s hard to imagine life before Google! Instead, we asked around and eventually found a friend of a friend who knew someone who volunteered for an orangutan sanctuary in Sumatra. Time went by before the organization called me. When they did it was a big panic because they were visiting Malang that very day and we had to guide them where to find the orangutan. I managed to track my brother down (no cell phones!) he did his best to explain where it was. These little villages don’t have regular street addresses, so it can be like finding a needle in a haystack. We were really anxious waiting to hear what happened. We learned that they did find her and that she had to be cut out of the cage because she’d outgrown the opening. It was this sad detail that haunted me all these years, but I wasn’t sure how I could write a story around it.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

MK:

There was never any other location I could have imagined setting the novel – especially because orangutans are only found in Indonesia and Malaysia.

All these years later, two news items brought the story together for me. I read two different news reports, one was about a group of students in Malaysia who staged an anti-palm oil play in their school. This caused a scandal and the students had to make a public apology. It demonstrated how far the Malaysian government feels it must go to protect their palm-oil propaganda.

The other news item was of activists demonstrating against supermarkets in Indonesia who were pulling products that displayed “palm-free” labels.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

So, it was combining the bravery of these young activist in the region, along with the memory of liberating our orangutan, how it all came together for me to write the novel.

OB:

If you had to describe your book in one sentence, what would you say?

MK:

Two middle schoolers in Indonesia, a keen activist and a chess whizz, come together to liberate a captive orangutan.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

MK:

I had planned to travel to Sumatra, Indonesia, to research orangutans and their habitat, but wasn’t able to do that because of the pandemic. I was very fortunate however to observe three beautiful orangutans at Melbourne Zoo’s Orangutan Sanctuary in Australia. I also relied on books, webinars, and documentaries. Leif Cocks, the founder of an organization called The Orangutan Project, was especially helpful along with a good friend in Toronto who is a primatologist and has studied orangutans in Borneo. For readers interested in learning more, I’ve included information in the backmatter of the book about palm oil farming, orangutans and The Orangutan Project.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

MK:

I dedicated Berani to my brother Andre because the inspiration for the story is one that we shared together. He still lives in the region and has no idea about the dedication. Last week I sent an advance copy to him in Kuala Lumpur. I’m looking forward to his surprise when he opens the book and sees his name.

OB:

What if, anything, did you learn from writing this novel?

MK:

I learned that the palm oil industry vs orangutan habitat destruction is a multi-layered and complex issue. It would be nice if the solution could be contained in a simple sentence: boycott products with palm oil and save orangutans! But sadly, it’s not that easy. Any monoculture farming such as rice, rubber, or coconut will have already destroyed, not just orangutan habitat, but elephant and tiger habitat as well. The fact is, palm oil yields the highest profit so that is what is planted by the huge agricultural companies that control the industry. For effective change, what is needed is to secure and preserve remaining rainforests to protect these unique ecosystems and their endangered species, and that requires government cooperation. Education is also needed to empower landowners with alternative under-canopy crops that can provide income without destroying the rainforests. Activism is an important part of this complex problem, to raise awareness and fundraise in order to rescue, rehabilitate, and release captive orangutans back into the wild so the endangered species’ population might have a chance to survive. While it is a daunting issue, I am encouraged by the many organizations who work tirelessly to tackle these issues, and I’m especially inspired by all the brave young activists who strive to make a difference. One of the reasons I love to write for middle-grade readers is that it’s an age when we are idealistic and are impassioned to stand up for important causes. To all of them I say: believe you can make a difference!

_______________________________________________

Michelle Kadarusman grew up in Melbourne, Australia, and has also lived in Indonesia and Canada. Her 2019 middle-grade novel Girl of the Southern Sea was a finalist for the Governor General’s Literary Award and a Junior Library Guild selection. Her previous novel The Theory of Hummingbirds was a finalist for the Forest of Reading Silver Birch Award, the MYRCA Sundogs Award, and the SYRCA Diamond Willow Award. Michelle lives in Toronto, Canada, and is looking forward to soon spending more time in Australia.