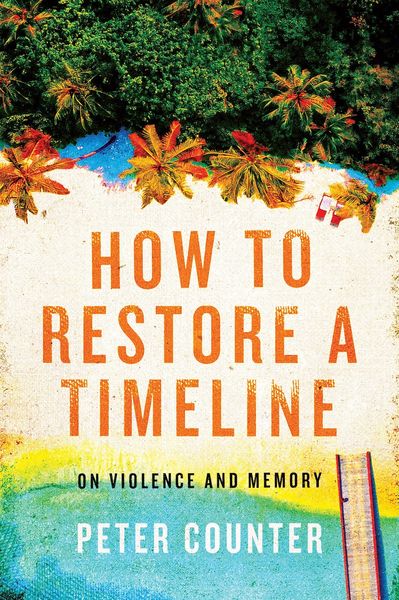

October 2023 Writer in Residence Peter Counter on Writing After the Unthinkable

Peter Counter was on a perfectly normal family vacation when the unthinkable happened: a stranger shot Counter's father, leaving Counter to drag him, wounded and bleeding, to safety.

It was a moment that changed everything that came after, and Counter, as one of CanLit's most interesting cultural essayists (his horror essay collection Be Scared of Everything was a particular joy to read), discovered over time that writing became part of his processing of the trauma.

How To Restore a Timeline: On Violence and Memory (House of Anansi Press) is the result, a hybrid book that blends Counter's deeply personal experiences with his trademark incisive and joyfully nerdy cultural (and subcultural) criticism.

Dealing with PTSD after the shooting, Counter examines the role violence plays in both the obvious elements of his cultural work (horror movies, videos games) and the less obvious ones (ASMR videos and the beloved British comedy panel game show Taskmaster, for example). After his experience, violence seemed to lurk around every corner, particularly in our media culture, which is so casually saturated with images of horrific deaths. Raw and moving while also showcasing Counter's wit and intelligence, How to Restore a Timeline plays with genre as it asks questions of what comes after the worst has happened.

We're excited to welcome Peter as Open Book's October 2023 writer in residence; this upcoming month we will have the privilege of hosting new writing from Peter on our writer in residence page. You won't want to miss new content from one of the most exciting nonfiction writers working today.

You can get to know Peter in our conversation below, where we talk about How to Restore a Timeline and his writing process, and he tells us about how he hopes others dealing with trauma can find companionship in his book; what happened to his first attempt, some years ago, to write his story in memoir form; and why he believes that no personal nonfiction can work without genuine vulnerability at its core.

Open Book:

How did your memoir project first start? Why was this the right time to tell your story?

Peter Counter:

How to Restore a Timeline is obsessively focused on the events of December 27, 2006 – the day a stranger shot my father in the chest on a Costa Rican pier and I dragged him back to the safety of our cruise ship. In one sense, this project started a few months after that. I was in theatre school at the time and tried to exorcise my budding PTSD through plays and monologues. That expressive behaviour never stopped. For me, trying to communicate how the event affected me manifests as a symptom. I can’t stop talking about it.

This is the right time for me to tell this story, in this specific way, because I have lived in the aftermath of trauma long enough to understand its shape and texture in my life. And that’s really what this book is about: the fine ornamentation of life after trauma, which we rarely talk about in deep detail. Two years from now I will have lived half of my life in a post-traumatic era – with its daily struggles and weirdness – and I’m finally confident in my ability to show readers how that feels.

When I was nineteen and traumatized, I felt alone in my experience of survival. I hope my book can find readers who need a guide, companionship, or relatable entertainment as they confront their own painful memories.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Is there a question that was central to this project? And if so, did you know the question when you started writing or did it emerge from the process?

PC:

For this book the questions was, “How can I tell this story in a way that communicates how it actually feels to have PTSD?” It’s a question that emerged properly when writing my previous book, an essay collection on horror called Be Scared of Everything. There’s an essay in that book called “On Madness” that tries to grapple with the difficulty of framing stories in which the conflict of a traditional plot has already occurred. To tell something post-traumatically is to reflect – a traditional beginning, middle, and end have already happened, and the survivor (in this case, me) is left to obsess over the poisonous memory of an event.

Since I have a background in reviewing TV, film, music, and video games, it seemed like the natural way to deconstruct a single moment in my life that already happened was through criticism. But instead of criticizing culture, I was applying critical analysis to the worst day of my life. This core question led me to the essay collection format, which helped show the fragmented, atemporal state of life after trauma. The central question never changed, and guided me through difficult creative choices, from outline to manuscript.

OB:

Did your memoir change significantly from when you first started working on it to the final version? Was there anything that surprised you about the process?

PC:

After writing the plays and blog posts I mentioned earlier, I took a proper run at a traditional memoir in 2016. I finished that manuscript, publishers passed on it, and I moved on. When I revisited that memoir after my first book was published, I found that it failed to express what I’d hoped. Unlike my experience with PTSD, the memoir I’d written wasn’t fragmentary, or haunted. It didn’t contain the crucial elements of culture I drowned myself in during the aftermath of my dad’s shooting. It was about a traumatic event, not the post-traumatic experience. I started over, prioritizing emotional accuracy over linear plot.

There were surprises during the actual writing process, too. I like to start a project with a thorough outline but remain open to change. That state of openness allowed me to see brand new media, like Jordan Peele’s Nope or The Batman, and incorporate it into the book. I am always consuming culture and art as a critic first, so when something aligns with what I’m writing I let it into my process and see how it interacts with an essay. That attitude helps me keep a sense of discovery alive throughout the creative process, which is always important in art, but can be particularly tricky to manage when you’re writing about a past event.

OB:

What do you do if you're feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

PC:

At the risk of sounding reductive, when I’m feeling discouraged while writing, I write. But there’s a trick: I have a broad definition of “writing.” Re-writing, editing, researching, active discovery of media, memory work, daydreaming next to a notebook – it’s essential to remember the process of writing a book is more than just sitting down at a computer and typing. If the typing isn’t working out, and I’m getting frustrated, I’ll look at my outline and consider some other tasks that will be a better use of my precious creative time.

For How to Restore a Timeline I had to consume and revisit a ton of media, including the television show Dragon Ball Z, Coldplay’s Viva la Vida album, the third season of Twin Peaks, Chuck Klosterman’s Raised in Captivity, and revenge films like Oldboy and Kill Bill. Writing criticism requires very active viewing, reading, and listening. When writing about Dragon Ball Z, you need to open yourself to being affected by a decades-old cartoon while also keeping your mind aware and critical of the artistic mechanics that are at work creating those effects. That’s important work. Which, I guess, is all a long way of saying, “When I’m discouraged, I watch anime and listen to Coldplay.”

OB:

Did you use any materials, documents, interviews, or other research that became part of the writing process?

PC:

I kept a journal during the cruise that brought my dad and I to the site of his shooting. In very early drafts of How to Restore a Timeline I quoted directly from it. I even considered just including the entries verbatim as a sort of found essay. None of that made it into the final manuscript, but it helped me understand who I was seventeen years ago, which was essential for being honest and vulnerable when trying to write about the past.

Other objects were so integral to the book that they form the basis of an entire chapter. “Inventory” is an essay structured through collected items: a DVD of karate lessons, a Final Fantasy VIII playing card, the cabin keys from the cruise ship, a carbon copy of the Costa Rican police report, a letter from a mentor—things like that.

My research was also active. I interviewed my family about their memories of the formal dinner we had in the ship’s dining hall several hours after the shooting. And, because I needed to write about guns for this book, I went on a field trip to a firing range and shot a few handfuls of bullets into some paper targets.

OB:

When you're reading memoirs, what stands out to you and makes a really great book? Were there any published memoirs you found inspiring structurally or otherwise while working on yours?

PC:

Vulnerability is what really makes personal writing stand out for me. My creative background is in experimental theatre, so I get very excited when that vulnerability is accessed through unconventional frameworks. The best example is Carmen Maria Machado’s In the Dream House, which was a major inspiration for How to Restore a Timeline. In my office, Dream House is always within reach, just so I can remind myself why it’s worth taking creative risks.

I also listened to the audiobook of John Jeremiah Sullivan’s Pulphead a few times over the course of writing my memoir. The essay “Peyton’s Place” was on heavy rotation. I am obsessed with writing that can express how it feels to live at the strange intersection of reality and pop culture, and Sullivan’s account of buying Peyton’s house from the teen drama One Tree Hill is the perfect example of how stories from TV can intrude on our physical reality.

OB:

What are you working on now?

PC:

Currently I am finishing up the outline phase for a third book. This one looks like it will be about technology and the occult. But first: I’m going to be the Open Book Writer in Residence for October!

______________________________________________________

Peter Counter is a culture critic writing about television, video games, film, music, mental illness, horror, and technology. He is the author of Be Scared of Everything: Horror Essays and his non-fiction has appeared in the Walrus, All Lit Up, Motherboard, Art of the Title, Electric Literature, and the anthology Empty the Pews: Stories of Leaving the Church. He lives in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia. Find more of his writing at peterbcounter.com and everythingisscary.com.