Poet & Wolsak and Wynn Founder Heather Cadsby on the Best & Worst Part of Being a Poet

Heather Cadsby has one impressive poetic c.v. With four full length collections under her belt, she also helped build Ontario's poetry scene, running series including the Art Bar Poetry Series, Phoenix: a Poet's Workshop, and events at the Axle-Tree Coffee House. She ran Poetry Toronto and even made time to found acclaimed publisher Wolsak & Wynn.

Cadsby is far from resting on her laurels though; her newest collection, Standing in the Flock of Connections (Brick Books) has been praised for its "wit and levity" (Prairie Fire Review of Books). Its energy and insight, candour and braininess jump off the page, welcoming readers to poems that are fierce, funny, and truthful.

We're pleased to welcome Heather to Open Book today as she takes on our poetry-obsessed interview, the Poets in Profile series. She tells us about the best twelve lines she's ever read, shares her favourite thing about being a poet, and teaches us something new (all about the triolet form!).

Open Book:

Can you describe an experience that you believe contributed to your becoming a poet?

Heather Cadsby:

Both my parents were detail oriented. I was bought up to see below the surface. My mother was a talker and loved to tell me stories about her life, including a detailed account of the death of her only sister. I was her eager audience. My father was quieter. He taught me to observe by looking. When he took me to art shows the only instruction was to walk around and find what I liked. In summers up north, he taught me how to sift sand to find small things.

OB:

What is the first poem you remember being affected by?

HC:

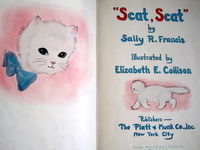

'Scat, scat/Go 'way little cat' from the book, Scat, Scat by Sally R. Francis. The pages had to be split open and on the blank insides my father made drawings of me (my hand age 2) and my things (my crib). This poem, about a cat that was abused, affected me profoundly. Now I am touched by these crude drawings hidden on the inner pages.

OB:

What one poem – from any time period – do you wish you had been the one to write?

HC:

I wish I had written W.B.Yeats’ poem The Lake Isle of Innisfree. It contains yearning, lilting rhythm, liturgical undercurrents, homesickness, natural surroundings and surprising metaphors. When asked, in later life, Yeats said that 'noon of purple glow' was heather reflected in water. Also, in the context (London in 1890), an acknowledgement of racism. To be Irish there was to be mocked. So, to have all these elements in a poem of twelve lines seems near perfection to me.

OB:

What was the last book of poetry you read that really knocked your socks off?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

HD:

Heavenly Questions (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010) by Gjertrud Schnackenberg. I have been a fan of her work since I heard her read in the 1980s. In this book she poses unanswerable cosmological, philosophical and mythological questions in her time of grief following the death of her husband. Her work is full of doors which open and dissolve and take her in and out of the hospital where he is dying. Her blank verse is rich with rhyme and dense images. Ultimately she presents courage, vulnerable dignity and a refusal to accept easy consolations and familiar adages. All of this is woven into a wild source of references, including Archimedes, Buddhist parables, the Arabian Nights, Lord Krishna, pencil graphite.

OB:

What is the best thing about being a poet – and what is the worst?

HC:

The best thing about being a poet is knowing it. Whatever else is going on in my life, I am always poet. It is knowing I can do this. And I do. This might seem like arrogance but I think it is more a survival tactic like reaching out. The worst thing about being a poet is having the poetry labelled or quickly read.

OB:

Do you write poems individually and begin assembling collections from stand-alone pieces, or do you write with a view to putting together a collection from the beginning?

HC:

I tend to write poems individually except when I want to pursue something beyond a single poem. For example I’m interested in triolets. They are a deceptively easy old French form. Only eight lines with some repeated, two rhymes, easy beat: iambic tetrameter. But if it’s going to work it really has to pack a punch which can be sad, funny, edgy, crude or sweet.

Also, there is a section in my new book titled Text Steps. These poems came from an interest in taking familiar adages such as "a stitch in time saves nine" and run around with them in the form of riffs.

___________________________

Heather Cadsby was born in Belleville, Ontario and moved to Toronto at a young age. In the 1980s, along with Maria Jacobs, she produced the monthly periodical Poetry Toronto and founded the poetry press Wolsak and Wynn. Also at this time, she organized poetry events at the Axle-Tree Coffee House in Toronto and Phoenix: A Poet’s Workshop. In recent years, she has served as a director of the Art Bar Poetry Series. Standing in the Flock of Connections is her fifth poetry collection.