"Prisons, Peacocks, Jarred Garlic" A Conversation with the Editors of Biblioasis' 2024 Best Canadian Series

Every year Biblioasis, the award-winning Windsor-based independent publishing house, releases their Best Canadian series, collecting the year's most powerful and innovative Canadian writing in short fiction, poetry, and nonfiction.

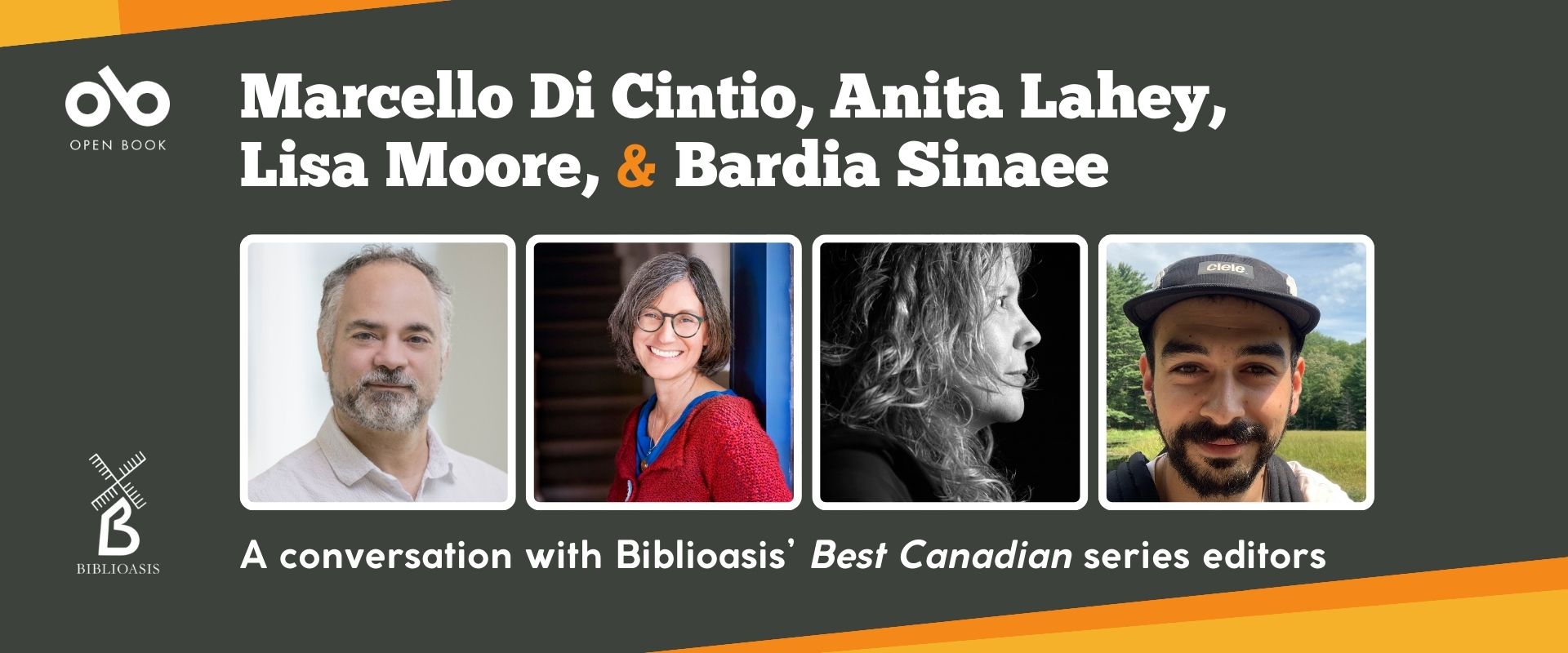

A guest editor is selected each year to curate the respective collections – a writer acclaimed in the category their anthology celebrates. The editors of the 2024 series, which are available now, are three of the most celebrated authors in Canada: Best Canadian Stories 2024 was selected by Lisa Moore; Best Canadian Poetry 2024 was selected by Bardia Sinaee; and Best Canadian Essays 2024 was selected by Marcello Di Cintio.

This year we are speaking with all three guest editors as well as Anita Lahey, who has served as series editor of Best Canadian Poetry since 2018 (and assistant series editor since 2014).

They tell us what it's like to take on the task of selecting pieces worthy of the "best Canadian" moniker, the exciting new voices they discovered while scouring the country for the most interesting new writing, and what they were looking for, from Moore's description of searching for a short story "like the breeze when you put your hand out the window of a speeding car" to Sinaee's explanation of "the bliss point" in poetry.

Open Book:

The “Best Canadian” qualifier is a hefty one. How did you select the pieces for this book, with the title in mind? What were you looking for when assembling it?

Marcello Di Cintio:

The essays that most stood out for me were those that made me think deeply about topics I wouldn’t have considered otherwise – prisons, peacocks, jarred garlic, for example. I also looked for craft. Just like an excellent poem or a short story, a well-written essay is beautiful.

Anita Lahey:

As series editor for Best Canadian Poetry, I annually recruit our guest editor and work closely with them once they have brought together a longlist from their months of reading—they’ll have scoured the pages of magazines and journals from the previous year, setting aside any poems they feel are worth a closer look, eventually bringing that pile down to around 100 poems. We read and discuss each poem on their longlist as they winnow down to the final 50 poems. (BCP’s guest editors are working with far more individual works than the prose editors, and our model, having a series editor work with the guest editor, makes for a more tenable process!) My role is to listen and pose what I hope are productive questions, as guest editors articulate their responses to, and their impressions of, each poem: why they were initially drawn to it, and whether it remains as compelling under repeated readings and closer scrutiny. I share my own take on the poems but I don’t actively push the guest editor toward or away from poems—I aim to help them find their most complete response to each one, to feel confident that they’ve given each poem a full and fair reading.

Every guest editor approaches the question of “best” in their own way, but threads that have run through the selections over the years relate to a poem’s ability to continue to offer something to its readers on subsequent readings; how well a poem has fulfilled its own particular promise and/or its author’s intent; and the element of surprise. Not that a poem should shock us, but you can tell as a reader when something unexpected has taken place in the writing—when the writer’s own direction or perspective has shifted, expanded, rerouted, tipped into a marvellous, momentary clarity—because that same jolt happens for the reader. This is when things get exciting. A poem that has surprised its own writer in the process of its making has achieved something more than competent or even accomplished completion: it has come alive. Often, these living poems are less polished than some of the merely “competent” poems—they may even exhibit blatant flaws. But they vibrate, they move. I’ve been involved with BCP for ten years now, and over that time—though each year’s mix exhibits something of that year’s editor’s sensibilities and concerns—I believe that most of the poems that have found their way between the anthology’s covers are undeniably, indisputably alive. And, whenever a reader arrives to encounter them, they open up anew, releasing some of the energy they contain.

Lisa Moore:

I was looking for short stories that were funny and/or terrifying or evocative and subtle and full of texture and images you don’t forget, emotional fire hydrants or something like the breeze when you put your hand out the window of a speeding car and feel the air lashing around it. Stories that absorbed the reader, particle by particle and reconstituted them. Made them think something they hadn’t thought before. Stories that opened the portal in the chest and made the reader’s heart bounce out like a prank can of nuts filled with snakes coiled tight. I wanted the stories to crack fusty notions of nations, or borders of any kind. Make us wonder: if there were such a thing as Canada, what would it be? How can a story be Canadian? Or anything but what it is? An utterance, an effort to bear witness, a tally, a tremor or quake. I wanted stories from the places we don’t always hear from. And as for ‘Best,’ every story informs all the stories that came before, and every story is informed by those stories, and the ones that I felt could touch a reader in this very hazardous moment, these were the stories I chose.

Bardia Sinaee:

I was looking for poems that I enjoyed. This was my primary criteria when selecting the longlist. Later, as I narrowed the longlist down to the poems that make up the anthology, I was looking for the poems that were rich, that were abundant with meaning, pleasure, and play. These poems offer enough to bear re-reading, but also withhold enough that they feel a little different each time you revisit them. In the poetry business, we call that the bliss point.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Open Book:

Are there any writers you discovered through this project? What, if anything, surprised you about the writers whose work you came to through this book?

MDC:

Most of the essayists in this selection were new to me, though I was pleased when I came across writers who I’d met years ago at some writerly function or another, and whose work dazzled me. I will keep an eye open for the future work of all these writers. My ‘to read’ list has expanded.

AL:

Every year I encounter new writers through BCP, poets whose work I’ve never read before, and every year I’m surprised afresh by what language, used deftly alongside the tools of the craft, can do. How every good poem, if met with willing openness, can let loose a tremor beneath the surface of our existence, introduce a crack in the casing, emit (or admit) an altered light. This year, those writers include (among others!): Sarah Lachmansingh, whose poem throbs with contained violence, fury and fear without raising its voice the slightest notch (she doesn’t even use a capital letter); Matthew King, who has forever recalibrated my relationship with ducks; and Misha Solomon, who has resolutely, without mercy, turned word, sound and meaning inside out, simultaneously opening up the “hole” at humanity’s core while offering his reader a solid “pole” to grasp as they take in the horror between the lines.

But this isn’t just about what’s new. Poets seldom stop writing poems, and many of them hit their real stride later in life, when they are far beyond such adjectives as “emerging.” Apprenticeship, for an author of any genre, can last a long time. One of the beautiful things about this anthology is how it brings together familiar, established, long-accomplished voices (often having found rich new veins to tap) with voices utterly new, entirely different, completely other. How those poems and their narrators talk to one another, often in unexpected ways, throughout the pages of the anthology, is one of the wonderful things about it. (So, too, are the poets’ commentaries on their work, which often tell the stories behind the poems’ making—and sometimes their un-making, and re-making.)

LM:

I was surprised by the variety of voices in the book as a whole. I am always surprised by that when I read an anthology of stories, so I don’t know why I was surprised. But I was; I am still. The unique quality of each voice; the intimacy on offer. How different parts of the country came alive across the sixteen stories. How every writer has such intricate and unique preoccupations. I knew the work of some of these writers very well, some I had never read before. But each story was absolutely new and surprising to me, and in rereading, they still surprise me.

BS:

Yes, absolutely. In fact, I had never heard of the majority of these 50 poets. Sarah Lachmansingh, Meghan Kemp-Gee, Michael Ondaatje — who are these people? Where did they come from? Poets are like barnacles: They attach themselves to a variety of surfaces and lead a sedentary lifestyle. They are highly adaptable and virtually impossible to eradicate. Despite concerted efforts from all levels of government, new ones are popping up everywhere.

Open Book:

How do you view the role of an editor in relation to an anthology or collection?

MDC:

The gig is difficult. I considered my role to curate a selection of work that was diverse in terms of voice, topic, and structure. I felt, too, that I had an opportunity to introduce readers to writers they might not have heard of before.

AL:

This is what I tell our guest editors: their job is to cast their discerning eye on a year’s worth of poems already carefully selected by journal editors, and bring forward those that they feel deserve a second, and possibly more lasting, audience. Their job is to follow their instincts as readers and lovers of poetry, to find the poems they most wish to celebrate, the ones that make them want to rush over to a friend and say, “You have to read this!” Their other job, as they set these poems aside, is to take note of the threads, nuances, effects, techniques, and moods that connect these poems, the resonances between them, and to come away with some sense of what Canadian poets (and the periodical editors who publish their work) were most propelled by, consumed by, or compelled by this year. Ideally they then articulate something of what they’ve gleaned, regarding where we’re at as a poetic literature, in their introductory essay to the anthology.

LM:

Behind every anthology is an infinite number of ghost anthologies of all the stories that could have been included, like the figure that multiplies in the crease of a hinged and angled set of mirrors. The things that make a story land are magical and inexplicable. There is something about how the stories react to each other, each story setting us up for the next, and also pulling the rug out from what to expect. I love how a short story takes up our attention, holds us, captivates – and then is over. But the trace of it follows us through the day and into the twilight and evening, perhaps not even words or phrases anymore, as the day wears on, as life floods in, as children come home from school, or we stop in traffic, just the vapour trail of an emotion lingers. That is the way I experience an anthology of stories, the whole of it on my shelf, one from years ago, or another from just a few years back, the feelings they evoked caught up in the colour of the spine, perhaps, or the memory of the year when it was released, a receipt from a café holding the page. I am not sure how they work, anthologies, but I am so profoundly grateful I had an opportunity to bring these stories together. And I am also grateful to read the next one and the next.

BS:

I viewed my role here rather straightforwardly: to pick the best poems that appeared in the magazines submitted for consideration, according to my taste. Best-of anthologies do not serve a transcendent moral or historical purpose; they are yearbooks, not canon. Canada’s literary and academic presses regularly publish anthologies organized around important political themes that are worthy of solemn contemplation. Best Canadian Poetry is not one of those books. Open it up at random and enjoy.

Open Book:

How did you approach assembling this year’s anthology as part of the legacy of this series? How is this year’s instalment different from or connected to the past Best Canadian editions?

MDC:

The pandemic features large in some of the essays. And the pandemic also influenced my curation, in a strange way. As I mention in the introduction, I found that the pandemic-borne anxiety hobbled my attention span and my capacity to consume art of any depth. I was stuck watching the same garbage television as everyone else. Through their depth and artistry, these essays served to pull me out of my COVID doldrums.

AL:

My job, as series editor, aside from what I’ve described above, is to, judiciously and when appropriate, bring the long view to the table—to bring in the broader context of the shifts in the series over time, and to help ensure that, while each guest editor is able to bring their own particular eye to the year in poetry, the series as a whole reflects the place contemporary Canadian poetry finds itself in each given year, and how that may have changed, or be inching toward change. My job is also to welcome readers to the anthology each year, those who have come to rely on BCP as a touchstone and a kind of yearbook, an annual reckoning, and those who are new to poetry as readers, writers, scholars—and all those who are curious about or drawn to the craft.

LM:

I could not think that way! I had to just be in it. Read every day, experience each story. Put them aside, shuffle them. Wish for the ones I loved but couldn’t fit. I think each anthology is a time capsule and I look forward to rereading this one, and others in the Best Canadian series to see what was captured about the time we live in. In order to create this collection, I dipped into the past, and read anthologies from the eighties, from the nineties and so on. How instantly those voices, even after a sentence or two, are utterly present.

BS:

I remember the excitement of being selected for the Best Canadian anthology and of finding new writers in its pages. To me, that is its legacy: it’s a place of celebration and discovery, like a party. In that sense, I hope this year’s instalment is no different from previous editions.

________________________________________________________

Marcello Di Cintio is the author of four books, including Walls: Travels Along the Barricades which won the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing and the W. O. Mitchell City of Calgary Book Prize, and Pay No Heed to the Rockets: Palestine in the Present Tense—also a W. O. Mitchell Prize winner. Di Cintio’s magazine writing has appeared in publications such as The International New York Times, The Walrus, Canadian Geographic and Afar. Di Cintio has served as a writer-in-residence at the Calgary Public Library, the University of Calgary, and the Palestine Writing Workshop, and he teaches nonfiction writing at the annual WordsWorth youth writing residency.

Anita Lahey’s third poetry collection, While Supplies Last, was published by Véhicule Press in 2023. She’s also co-author of the graphic-novel-in-verse, Fire Monster, a collaboration with artist Pauline Conley (Palimpsest, 2023). Her memoir The Last Goldfish: a True Tale of Friendship was a finalist for the 2021 Ottawa Book Award. Anita first joined Best Canadian Poetry as assistant series editor in 2014, and has served as series editor since 2018. She lives with her family in Ottawa.

Lisa Moore‘s books have won the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize and CBC’s Canada Reads, been finalists for the Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize and the Scotiabank Giller Prize, and been longlisted for the Booker Prize. She lives in St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Bardia Sinaee’s poetry, essays, and book reviews have appeared in magazines throughout Canada. His first book, Intruder (House of Anansi, 2021), received the Trillium Book Award for Poetry and was shortlisted for the Gerald Lampert Memorial Award. He is the guest editor of Best Canadian Poetry 2024 (Biblioasis). He was born in Tehran, Iran, and currently lives in Ottawa.