Quill Christie-Peters Discusses ON WHOLENESS and Writing Toward Collective Liberation

In a dazzling new work of nonfiction, Quill Christie-Peters explores what it means to live fully engaged with our bodies, our ancestors, and the world around us. Through stories of birth, parenting, creativity, and care, the Anishinaabe visual artist invites readers to consider the body as both a site of pain and a source of profound healing.

Christie-Peters writes with clarity and courage, sharing personal experiences of gendered violence and her father’s survival of residential school while tracing the nefarious ways that colonialism works to separate people from themselves and their communities. Her reflections are both intimate and expansive, grounded in the belief that reconnecting to the body is an act of resistance and a step toward liberation.

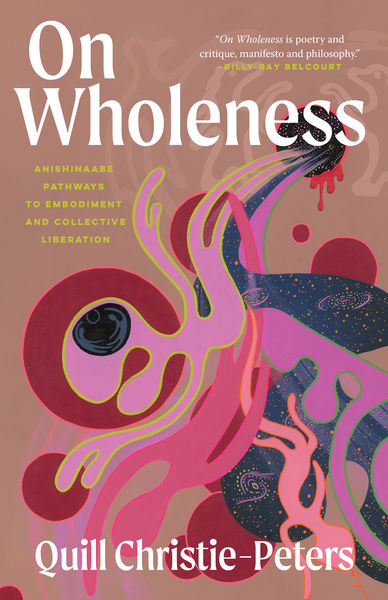

On Wholeness (House of Anansi Press) is a deeply moving and thoughtful work that reimagines how we understand the self. Christie-Peters shows that healing begins not in isolation but in relation with land, kin, and spirit, and that wholeness, however hard-won, is something we can all move toward together.

Check out our fascinating interview with the author, right here on Open Book!

Open Book:

What themes or ideas are you exploring in your book?

Quill Christie-Peters:

My book explores what it means to be whole as an Anishinaabe person contending with the settler colonial world. I situate wholeness as an expansively embodied state that allows me to be in conversation with my ancestors, my homelands, the galaxies who birthed me, and the waterways of Nezaadiikaang who sing to me in the night. The book is really an amalgamation of my life’s work, approached through the overarching framework of becoming whole.

It came to be through a nudge from my editor, Shirarose Wilensky, who asked if I would ever consider writing a book. Writing a book was always something I wanted to do, but it felt so daunting that I never initiated the process myself. Through Shirarose’s question, I became instantly inspired and began to think of a way to weave parts of my work together — Anishinaabe parenting as a responsibility to worldbuild, creative practice as wholeness, pleasure as a liberatory invocation, and our collective responsibility to build practices of joint struggle.

I am passionate about the subject matter because I live it and it deeply impacts myself, my community, my nation, and the world. I take a deeply embodied approach to writing that centres my lived experience while also considering ancestral, land, body, and community-based knowledge. I am passionate because I want a better world for us all, one that is rooted in justice and liberation for all. To write for this better world is a responsibility that I take very seriously.

OB:

Is there a question that is central to your book? And if so, is it the same question you were thinking about when you started writing, or did it change during the writing process?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

QCP:

The central question of my book is: What does it mean to be whole in the settler colonial world? When I started writing, I was oriented toward charting the practices that bring me closer to my own wholeness as an Anishinaabe artist, educator, and mother.

As I wrote, I was heavily influenced by the escalation of genocide in Palestine in October 2023, and the central question evolved. By the end of the book, the question had become: What role does wholeness play in our collective liberation? I love that this guiding question evolved because it mirrors my own growth as an Anishinaabe person who was deeply moved by our world during this time — and who still is.

I began to think more deeply about wholeness as a tool for liberation, and how our radical embodiment resources us to better resist and transcend the violences of settler colonialism and imperialism.

OB:

A lot of nonfiction prizes and anthologies have expanded to welcome more personal nonfiction as well as strictly research-based nonfiction. What do you think of this shift within the genre?

QCP:

I think this shift is great and much-needed. It makes space for Indigenous writers. As an Anishinaabe writer, it is central to my worldview to speak from my lived experience as the foundation of my knowledge systems. My personal experiences, ancestral knowledge, body-based knowledge, and community-based knowledge are all valid components of an Indigenous research methodology.

In addition to being a writer, I am also an educator. When I teach, I do so in a way that honours my Anishinaabe worldview, which includes centring lived experience as a valid form of knowledge production. For Indigenous peoples, personal experience is at the heart of our knowledge systems. This is often at odds with a colonial approach, in which knowledge is something you must obtain outside of yourself.

My book is an articulation of an Anishinaabe research methodology. My own experiences are at the centre, scaffolded with familial, community, and nation-specific knowledges. Importantly, these experiences are expansive — they touch upon my ancestors, my body, and all of the relations who make me who I am.

The shift toward valuing personal nonfiction is necessary and just. It allows Indigenous writers to be recognized within their own worldviews and ways of knowing.

OB:

What do you need in order to write — in terms of space, food, rituals, or writing instruments?

QCP:

Sadly, I largely cannot write in the comfort of my own house — I found that out the hard way! Many failed writing days ended with a very clean house. I write best in busy public places, such as cafes, while listening to melodic doom metal. I frequented so many coffee shops while writing this book in the Thunder Bay, Kitchener, and Toronto regions. Now that the book is finished, it’s so cool to revisit those haunts and have specific memories flood in.

Something that was really helpful for me was learning and honouring my own limits when it comes to writing. Early on, I would set aside entire days for writing, only to feel frustrated when I didn’t accomplish as much as I hoped. I realized that I can write for two to four hours per day, max. Surrendering to those limits was beautiful. It reminded me that writing itself is only one part of the process — the thinking, the immaterial, the relational — all of it happens every day, in every moment.

OB:

What are you working on now?

QCP:

Right now, I’m still recovering from writing this book, haha. But I’ll soon begin my next project: a children’s version of On Wholeness. This picture book will be for babies and their parents — a lullaby that invites the wholeness of child and caregiver to be spoken into existence and celebration.

I’ll be translating some of the main themes of On Wholeness into an invocation that comforts and affirms children and caregivers’ internal knowledge. It will celebrate how they carry the irrevocable love of their ancestors, spirits, and the great beyond within their bodies, while affirming parents’ responsibilities related to worldbuilding.

As a visual artist who specializes in acrylic painting, I’ll also be illustrating the book with starscapes and images of our ancestors caring for us and whispering visions of a better world.

_____________________________________

Quill Christie-Peters is an Anishinaabe educator and self-taught visual artist from Lac des Mille Lacs First Nation located in Treaty 3 territory. She is the creator and director of the Indigenous Youth Residency Program, an artist residency for Indigenous youth that engages land-based creative practices through Anishinaabe artistic methodologies. She holds a master’s degree in Indigenous governance on Anishinaabe art-making as a process of falling in love. She has spoken at Stanford University, the University of Toronto, and California College of the Arts, and her written work can be found in GUTS magazine and Canadian Art. She is also a mother, beadwork artist, and traditional tattoo practitioner following the protocols of her community. All of her work can be found at @raunchykwe.