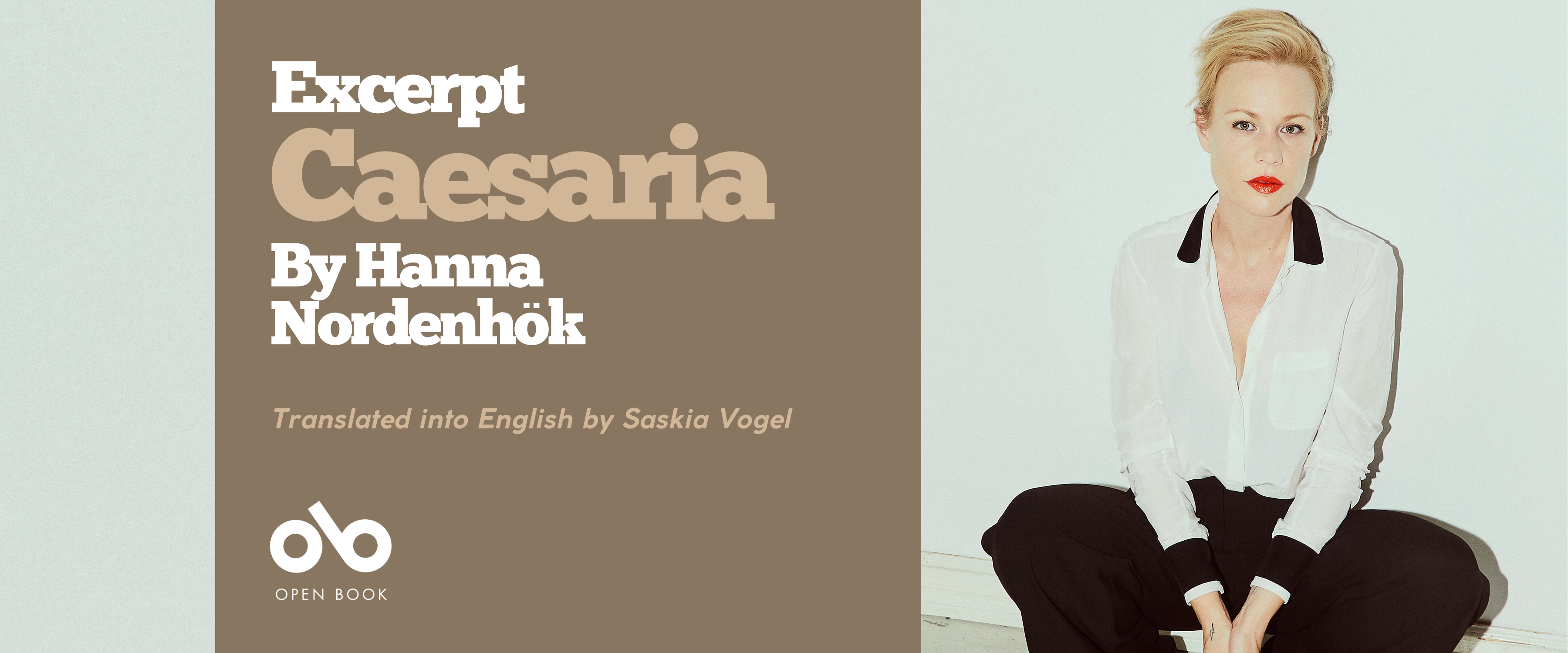

Read an Excerpt From Caesaria by Hanna Nordenhök (translated by Saskia Vogel)

The folks at Book*hug Press are known for publishing works in English translation from exciting and eclectic authors, hailing from all over the world. In Hanna Nordenhök, they've found another brilliant writer who has already been feted in Sweden for her work, and who is also an acclaimed translator in her own right.

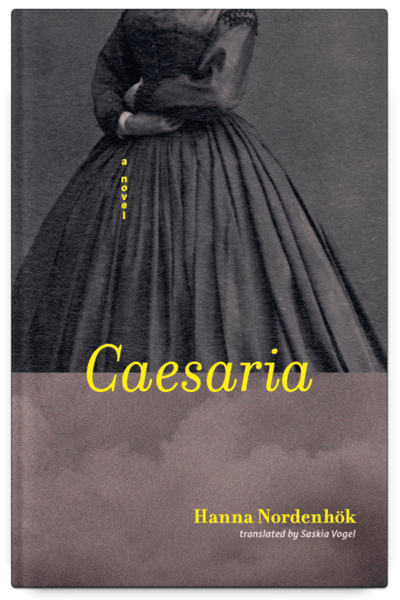

Nordenhök's latest is the novel Caesaria, an atmospheric modern gothic about a girl sequestered in a remote country estate in nineteenth-century Sweden, kept there as a trophy by a twisted obstetrician who delivered the titular character years ago by caesarean section. While full with dread and tension, the novel is told in beautiful, dreamlike prose that catalogues the comings and goings on the estate as Caesaria narrates her story and the encounters that she has with mysterious inhabitants and visitors to her makeshift prison.

The novel takes an unflinching look at issues of gender and class, and the subjugation of women and the poor. It's a frank rumination on the ways that a body can also be a cage, one that speaks to profound and astonishing truths through the story of one unique girl

We're thrilled to share an excerpt from the translated novel today on Open Book, free for all of our loyal readers!

Excerpt From Caesaria by Hanna Nordenhök (translated by Saskia Vogel).

It was the night little Beda and I took to the forest that I realized I’d never be able to leave Lilltuna and the room with the East Indian wall clock. Its steely eye would stare back at me forever. And I’d never learn anything other than what I had learned there.

Snow now.

I sleep with my body pressed to the stove; I’ve laid out all the objects so I can see them. The cold crackles in the tiles. At dusk the animals draw nearer to the house; they’re seeking heat and food. At first they stand at the edge of the forest, trampling, then they grow bolder. Come daybreak, a hazy sun.

Snow.

The pond in the forest was also like an eye when Beda and I drew near it at dawn, the morning after we’d taken to the woods. It was like in my dream, but without the flames. Late summer. The eye was grey and still, framed by cattails and reeds, a liquid pupil: perhaps it had always been watching us. The edge of trees on the far bank steamed in the gritty light. A distant fox. I was wearing my wadmal trousers, I was wielding the Sceptre, my body was Bandaged and Bound. A streak of autumn through the August air. Beda complained. We’re almost there, I said, coaxing her now. I offered her my hand. A bird screeched. Then the sky broke open and the sun’s flaming orb lit up the pines, its light corroding the tangle of branches. We had arrived. And yet we’d got nowhere. And it was clear to me: we had got nowhere.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Then morning arrived, and we were retrieved.

It was my twelfth birthday.

The first thing I learned was Lilltuna, and Lilltuna belonged to Doctor Eldh.

Wattle fences criss-crossing the wetlands. Magpies above the trees. The smell of young turnips and the cat shit in the cellar.

I learned the nails in the barn walls, I learned my knuckles, I learned the moonlight pooling on the floor tiles in my nursery on clear wintry nights. I learned every inch of the square piano, too: I sat on the screw stool with its embroidered carnations, I wore the yellow dress with the puffed sleeves, I played the polka and “Für Elise.” The keys were already cracked and veined like an old person’s fingers.

I learned the keys, I learned the screw stool.

During my Saturday baths, down in the kitchen, after my body had been lowered into the steaming tub, I always sat stiff and upright while my still-damp hair was set in tight braids: outside, the infinite evenings. Night birds volleyed messages until I drifted off.

The first and last thing I learned was Lilltuna. I slept, I woke, I played with my dolls: outside was the forest. Now and then that particular light fell across the barn and the pasture, a yellow-streaked, savage blush, as if to remind me that Lilltuna was chosen and blessed. When the toys in my nursery broke, I simply added them to the wish list I kept in the lockable drawer in the little nightstand, making sure to cross out the old entries each time before handing it to Doctor Eldh. New toys would always arrive to replace the discarded ones.

After Beda and I were retrieved from the pond in the forest that morning, I was tucked back in with the old horse blanket in the nursery. My knees chafed against the wool through the linen. I smelled of forest and rotten apples; I watched the late-summer flies slowly die between the double set of windows. On my sixteenth day of bedrest, Doctor Eldh arrived.

He came from the city in a hired cabriolet; he sat in the rattan armchair at the foot of the bed; he steepled his fingers. The armrests groaned under his great elbows. Slender pulsing veins at his temples, his jaw tense beneath those billowing whisker-clouds. I leaned on him, half-squinting, my eyelids reluctant and heavy, as if the forest’s enchanting air was still trembling against my face, just as it had against Beda’s and mine that morning in the glowing light, at the edge of the universe. He was disappointed, that much was clear. His feet were restless. A red-tinged evening light lay upon his high, untroubled brow. I listened to the silences before his words, to the rowan’s windblown branches whipping the nursery window. The smell of old Mam’selle Fanny’s coffee rose from the ground floor. I turned to face the wall, I let him begin. He spoke the same words he always had, tasting them, enticing himself with them so they sounded unexpected and new, though the story he told was the same: the story of my Creation. His forehead in the light, the armchair’s gentle groan. The words like a crystal of rock sugar about to burst on his tongue. Then: How the woman who would soon become my mother had come to him in distress. How the cabriolets had skidded across the cobblestones in the golden summer rain, outside the city’s lying-in hospital. How in the light of the oil lamp, that scrawny, shabbily dressed woman’s swollen abdomen, its web of veins close to the surface of her stretched skin, had taken on a deep blue sheen: later, too, when she was already dead, how her belly had appeared to ferment and turn blue, how her body had lain there on the bed in a stream of daylight, by then opened and emptied and sewn back up with sturdy catgut sutures.

The rainlight, the clang of instruments in the enamel bowls. Later: how he cut me out and into life, as one lifts a shimmering pearl from an oyster.

Sometime after that, he took me to Lilltuna.

___________________________

Hanna Nordenhök has been awarded several major literary honours for her work. Her novel Caesaria (2020)won Swedish Radio’s Literary Prize and was shortlisted for Vi’s Literature Prize. Nordenhök also works as a translator from Spanish and has been praised for her translations of Fernanda Melchor, Andrea Abreu and Gloria Gervitz. She lives in Stockholm.

Saskia Vogel is the author of the novel Permission and a translator of more than 20 Swedish-language books. Her writing has been awarded the Berlin Senate Endowment for Non-German Literature. Her translations have won the CLMP Firecracker Award for Fiction (Johannes Anyuru’s They Will Drown in Their Mothers’ Tears), have been shortlisted for the PEN Translation Prize (Jessica Schiefauer’s Girls Lost), and supported by grants from the Swedish Arts Council, the Swedish Authors’ Fund, and English PEN. She was Princeton’s Translator in Residence in fall 2022 and lives in Berlin.