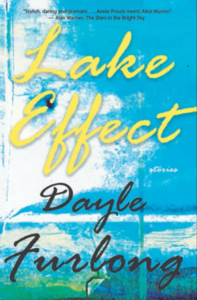

Read an Excerpt From Dayle Furlong's Powerful New Collection, Lake Effect

Set in the Great Lakes region, the stories of Toronto-based author Dayle Furlong's new collection Lake Effect (Cormorant Books) follows those on both sides of the border as they struggle with love, fear, desperation, and change.

An incarcerated Chicago mother raising her child within prison walls. A Thunder Bay policeman scouring the streets for his missing stepson. A Michigan man braving a dangerous storm to sneak his Iranian-Canadian girlfriend across the border. Lake Effect's cast of characters prove to be relatable and painfully human, and Furlong uses them to great effect in bringing her readers' attention to larger social issues. Employing a refreshing balance of imaginative description and well-crafted narrative, the stories in this collection are reminders of the hidden triumphs and tragedies of every day life.

We're very excited to feature an excerpt from Lake Effect on Open Book today.

Excerpt from Lake Effect:

What Follows the Falls

I watch the mist from my kitchen window. Coils hang above the gorge, white as a mountain peak, opalescent, dense. Maternal rotundity deceptive – it has no soul, it won’t save you if you fall. It can’t carry your burdens. But I stare at it now, in the hopes of finding concealment in the mist. I want it to swallow the truth. Hide what I’ve just seen.

I suppose I don’t need what she took. I want it. But I don’t need it. She doesn’t need it either, but she definitely wanted it. So she helped herself, crept into my daughter’s room uninvited and rummaged through her closet. I don’t need what she took, like I said, but it’s a keepsake and mine to decide whether I can part with or not.

I should have listened to my husband. He’d warned me, when I met Amy eight months ago, said he didn’t want her in our house. He must have seen something I didn’t. Something furtive, sly in her thin lips and over-sized eyes, the way she ingratiated herself with me. Perhaps I’d been too harsh with her last night? I only raised my voice a little. I’m not sure what to do now. Should I, as my girls say, ice her? There are more things about her I’ll miss than just using her Target employee discount.

I finished washing the dishes, from last night’s supper, and set up my powder-blue Keurig. Dougal had already walked the dog and the girls were at their Saturday morning ballet class. We’d finally get a moment alone. I’ll tell him what happened. I wiped the machine and discarded the pod. I was on the hunt for this coffee maker when I met her. Our love of coffee brought us together, and I wonder if when she said she’d do just about anything to get a coffee it wasn’t a proceed with caution sign in and of itself.

I couldn’t see the red and white sign for housewares. I was lost in linens, fingering the hand towels, evaluating their thread count when Amy bumped into me with her cart.

“Sorry,” I said.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Amy stared at the children’s clothes draped over the crook of my elbow.

“Watch that Starbucks don’t stain your clothes,” she said.

“It’s empty, but thanks, my girls will kill me if I stained their new shirts.”

She bristled then sighed, asked if she could help with anything. I told her I was looking for a Keurig coffee maker. She left her cart, full of towels to be re-shelved and took me to housewares.

“I like this blue one,” I said.

She told me she had the same one. We bantered a bit, teasing one another about caffeine addiction, discovered we both liked our coffee the same way, milk with two sugars, and we’d both watched Big Little Lies on HBO over the winter religiously. And despite her lack of exposure to the term we considered ourselves irreligious. Give me your purchases, she’d said. And when I’d said, Excuse me? She’d surprised me by offering use of her staff discount. She could ring them through, no problem.

She said it was time for her break and would I like to join her for a coffee at the Starbucks? When Dougal and the girls found us we were deep in conversation about affordable healthcare.

“The next time you cross the border, come and have lunch with me,” said Amy.

Why not? I thought. It couldn’t hurt. I’d enjoyed talking to her. It was so hard to find women to hang out with. My job as a copy editor kept me at home. I proofread city contracts from Dougal’s office mainly, by-laws for daycare licensing, garbage collection and zoning regulations, and when the girls came home from school my evening consisted of driving them here and there, helping them with homework and making their lunches for the next day, I had little time to socialize.

“Run don’t walk,” said Dougal in the car ride home.

Why does he always see the bad in everything?

“Something not right about her,” he said.

“You’re overreacting.”

“She’s a bit off. Her voice.”

“Too loud for sure, but honey, we’ve got a lot in common.”

So I went. Drove across the border from our house in Niagara Falls, Ontario to her tiny white house in Niagara Falls, New York—a run-down, empty town whose better days had passed, with citizens who personified long-gone glory as they wandered through the city empty-eyed, weary, and determined.

It was a Monday afternoon. I took the day off and she did too. She waited for me at her front window when I pulled up. Once inside she gave me a tour: modest kitchen, cozy backyard, powder room with black and white tiles, airy living room. Her bedroom upstairs smelled like coconut, a plug-in tropical air freshener, she said, to hide the smell of her husband’s cigarettes.

She opened a closed door at the end of the hallway to reveal a child’s nursery. A gorgeous little room, filled with all the cute things Target sold. A white crib and change table, a bureau with a small library of classic children’s picture books. The walls were painted peach.

“I didn’t know you were expecting,” I said.

“More like hoping,” she said.

She told me she’d been trying to get pregnant for over six years. She was sure it would happen soon. She put the nursery together a few years ago when she thought she was pregnant. She saw no reason to dismantle it.

“Every week I change the sheets,” she said as I touched the comforter with baby animals cavorting on a grassy plain, “no sense letting it get dusty.”

I was impressed by her resilience in the face of a continuous cycle of disappointment—every four weeks for six years, dealing with that feeling of failure—yet on the other hand I found the whole thing strange. She chatted away as if there was nothing at all hopeless about her situation, led me downstairs for lunch listing off potential baby names, things she wanted to do for birthdays, how much she longed to make sweet potato purees. She was so full of optimism that despite how odd it seemed I rallied to her cause.

“Of course it’ll happen,” I said.

“Do you think so? My husband—”

“What do men know?”

And we traded stories about signs of pregnancy, which multivitamin had the most folic acid. Foods to avoid.

“Coffee,” she said.

“No!”

“Yes. No more than one cup a day for me.”

I held up my mug and we toasted her final cup of the day.

-

A week later I sent an email suggesting we drive down to Buffalo and spend our next day off at the Albright-Knox Museum.

“What are we seeing?” said Amy as she climbed into the passenger seat of my car.

“There’s a lot to choose from,” I said.

I wanted to see the Operation Sunshine Exhibit by Buffalo-based artist and Professor Joan Linder.

“I don’t want to see anything that’s just splashes of paint,” said Amy.

Jackson Pollack it wouldn’t be then.

“Or anything made with coat hangers or toilets.”

In the gallery I directed her to the exhibit room. It was filled with hand-drawn replicas of documents related to toxic waste sites in Buffalo, Tonawanda and Niagara Falls. A bright orange book cover entitled, Salt & Water, Power & People: A Short History of Hooker Electrochemical Company on 9 ½ by 12 ½ paper hung on the wall.

“My grandfather worked for Hooker,” said Amy.

Hooker dumped 20,000 tons of toxic waste in the Love Canal neighborhood along the Niagara River and in the 1970s families were forced out of their homes as illnesses took root in the residents. We looked at a hand-drawn copy of a radiation study paper.

“This is so sad,” said Amy.

“Let’s go to the café eh?”

In the bright café Amy told me she wanted to go to Lily Dale Assembly in Western New York. A place where mediums channelled the dead, chakras could be cleansed, and if you were lucky, you could hear one of the founders of contemporary Wicca give a lecture.

“They’ll give me crystals to place on my belly,” said Amy.

Did she really believe something external influenced something so, well, internal?

“And a package of cleansing teas to drink before bed.”

Cleansing teas?

“I hope this will help me get pregnant,” said Amy. She wanted it so badly. I knew what it was like to want something and not get it. It’s not as if I hadn’t had doors close in my face while trying to conceive. I’d had two miscarriages before I had my first baby. I had faith in her. She’d managed to cut down on the coffee. I knew she could do this.

“Will you come with me to Lily Dale?” asked Amy.

-

“I’m going to ask my dead husband where he left the keys to the liquor cabinet,” said the old woman and laughed, smearing mauve lipstick on her grey overbite. I nudged Amy, asleep, head nestled on my chest, flat, blistered spots along her hairline. She sat up and wiped drool from her mouth. The bus pulled up to the gates of the Lily Dale Assembly. A group of women at the back of the bus finally stopped singing about rainbows and fairies.

“I want coffee,” said Amy.

“Don’t,” I said.

“They can work miracles here,” said the old woman and reached across the aisle to pat Amy’s hand, “they helped me quit smoking last summer.”

“I’ll need a miracle,” said Amy. She stood up, a gargantuan katydid in second-skin jeans, spindly limbs knocking against the backs of seats as she waited in the aisle while the bus turned in the parking lot. The Saturday bus had picked us up at six a.m. down the street from Amy’s. I already felt tired.

“I can’t get pregnant. Been trying for six years,” said Amy to the old woman. She wanted a healing. She hoped it would help conceive a baby. I’d wondered how something as nebulous as a “healing” would help.

“Best way to get over your problem is get under your husband,” said the old woman. The bus came to a final stop outside arched gates proclaiming Lily Dale as the World’s Largest Center for the Religion of Spiritualism. We walked inside, stumbled over potholes on unpaved roads in our thin sandals. American hazelnuts and bitternut hickory trees tangled around the houses. Pastel-coloured bungalows with signs advertising mediums hung out front. On one, a welcome sign with stout sunken letters burned into the wood that said Come sit on my porch.

It was quaint. Welcoming. I might enjoy being here for an afternoon.

The crowd, mostly women, all seniors, except for a young blind man and his sighted guide, a muscular blonde in a Melvins t-shirt who fussed over proper handling of the cane, walked in groups of two toward The Healing Temple, a white building with Greek Revival–style columns. A woman wearing a plastic pink laurel wreath and a white linen dress descended upon us from behind a plump rosebush. “Welcome to Lily Dale,” she said, inserting the sound of the letter h after the w in welcome.

Amy grabbed both her hands. “I’m Amy and this is my friend Candace.”

“I’m Athena, one of the spiritual leaders. I’ll bring you to your session shortly.”

She gave us a strip of cloth and asked us to place it on the tree with the other purple, blue and raspberry coloured bows.

“I’m not going inside,” I said. I spotted a sign for a coffee shop in the distance. I could go and have a drink while she was in the healing session. Amy would never know. I didn’t get the chance within minutes Amy came out of the temple.

“I hope this works,” she said and tied her ribbon to the tree.

“Let’s get something to drink, eh?” I said.

We walked toward the café. Pink and spring green cushions spilled out of wicker loungers crowded on the verandah. Wind chimes tinkled above. A handful of cats and a toddler roamed around the room. A barista held her arms open as if there were a crowd of us she wanted to embrace.

Amy ordered two lavender teas. I coughed when I took a sip.

“The healer told me to grab my fate with both hands,” said Amy.

“You paid how much money to hear someone tell you that?”

“Don’t mock. I’m going to see an astrologer now.”

I accompanied her to the astrologer’s bungalow. It would take an hour so I set out for a walk. Paved residential streets in front of homes painted plum, red and Robin’s egg blue. Personalized license plates read “medium”. It was a community for the highly-skilled, amateur mediums need not set up shop. The place gave off an air of authority. This wasn’t just a circus sideshow. They were believers.

I entered the Leolyn Woods. Purple pansies grew in patches around the Pet Cemetery. I was put off. I thought of that horror novel, who wouldn’t? I walked faster. Didn’t dare look at the headstones. A blue jay fluttered amongst the blackberry thicket. My heart softened, a beast alive.

I walked by Inspiration Stump. A moss speckled stump encircled by a wrought-iron gate with bouquets of withered pink roses on the surface. Rows of pews faced the altar of the stump, it began to fill up with people, women mostly, who came for what they called the One o’clock Stump. A Reverend stood beside the stump and prayed. I slowly backed away as he thanked God for the continuity of the stump. I assumed he gave praise for the life-cycle of the tree, analogous to our own cycles of birth, death and the supposed afterlife. Notions of the afterlife were central to their doctrine. And what went on there? Did pets make audible noise? Trees? What about insects?

I checked my watch. Another thirty minutes until Amy was finished. I wandered a bit more, dying for a coffee, until I found The Fairy Trail. A white, undecorated trellis marked the entranceway. A handwritten note stuck to a tree said “glitter is litter please don’t put it on the trail”. Did people scatter glitter here? In the hopes of what exactly—illuminating the spirits on the trail? Farther along the trail, as the result of some ritual, whose meaning escaped me, were fairy houses made of plastic, seashells, pine needles and twigs. Some fairy houses had tinsel streamers while others had paper. It was flashy and loud and overwhelming.

I stopped at a large recess in the ground. A note posted to a tree explained that this was a crater where the fairies had once landed. I stopped to rest. Despite my lack of comprehension I relaxed. Spears of sun like translucent vines fell from the trees. The Maples, with their delicate leaves caressed the air, stirred breeze and carried moisture from my skin, ushering in a silky cool.

My girls would love it here. I thought of that spring day, not unlike this, when they were toddlers and I’d taken them down to the falls. The mist over the falls seemed like an entity unto itself. We sat on a grassy hill and they played with my hair. They loved to run their pudgy little hands, rubbery and soft like plasticine, through my hair and put it in piggy-tails, as they called it, or pony-buns. My eldest said my hair had a lot of laughter, rainbows and fairies in it. I thought her innocent comments charming. I wonder now, surrounded by a world created by adults, reflecting their hopes and dreams, if there was an innocence that the women who came here still possessed?

Amy had a childlike ability to believe. Would it help her become a mother? I stretched, stood up and made my way to the exit. I found Amy waiting outside.

“She pulled the Four of Cups and the Two of Swords,” said Amy.

“What does that mean?”

“One of us in the relationship wants a baby the other one doesn’t.”

My brow crinkled in disbelief.

“Better I don’t have a child with a man who doesn’t really want one.”

“What are you going to do?”

“At forty I’m certainly not going to start looking for a new man.”

I suggested we have lunch down by the beach. Small crests of water luminescent from the sun, like soft butter curling under the pull of a knife, veered toward the shore and frothed at the shoreline. We took off our shoes and rolled up our jeans. We stood side by side on a rock and Amy hung her head. She was quiet for a minute or two. I saw a dead pan fish, hook hanging out of its mouth, rolling on the shoreline. Its guts were loose. It had broken free from a fishing line.

Amy’s lip quivered and she cried. I grabbed her hand and pulled her gently back to shore. We sat on the grass and I handed her a tissue. She tore into a turkey sandwich, mayonnaise gathering on her lips. Earlier that morning I’d made sandwiches for my husband, two for my daughters and two for us—all the people I felt a sense of responsibility toward, the people I instinctively mothered.

-

“I just don’t want her here,” said Dougal.

Dougal’s emotional aloofness coupled with a flagrant sense of superiority—both traits honed from his days as the bullied nerd in a blue-collar family—kept most people away. All of his various facades, however, melted when he was with me. With me he was soft, tender, kind, loyal and vulnerable, traits I forget about when he was in this mood. We’d met at the Brock University Library. He saw past my stringy hair and out-of-style glasses, or so he said later, and saw gentleness in my eyes. I was hiding in the library, like I did almost every day before a lecture, because I’d never quite hardened myself against the bullying I’d endured in a similar family and felt safer alone. I felt a connection with Dougal I’d never experienced. We married shortly after. Travelled to Cuba for our honeymoon. Sat on a tour bus and answered the guide’s questions about organic farming, the “special period” in Cuba’s history, Castro’s policies and the fall of communist Russia while the others on the bus only wanted to talk about the quickest way to get more Rum. Like I said we were complete nerds. But with Amy I didn’t feel that way. I felt like I had something she coveted and not the other way around. I could expose her to art and she was receptive. I could talk about being a mother and she didn’t make me feel stodgy. It wasn’t often I gravitated toward others but with her I glided straight into her open offer of friendship.

“I’m going to invite them,” I said.

And I did. They showed up on a Friday evening after work. Dougal agreed, not without protest, to attend my dinner party.

“Dang good coleslaw,” said Amy’s husband Mike.

Dougal looked at me with wide eyes. Our golden lab sauntered in, thick tail buoyant, and begged for a scrap. Dougal took her gently by the collar and put her in the doghouse.

“I hate dogs,” Mike said when Dougal returned.

Dougal stiffened.

“We get all kinds of strays begging outside Target,” said Mike.

“Call animal services, they’ll take them in,” said Dougal.

“I says to my staff, ‘I’m the Manager here and we gotta do something about the strays coming to the dumpsters behind the store,’ and staff says they already called animal services, and I says, ‘That’s not enough. We gotta get tough on those bastards—’”

“The girls Mike” said Amy and put her hand on the collar of his plaid shirt. My daughters weren’t paying attention. They had tablets on their laps then soon drifted off with a plate of cookies to the basement.

“Those animals are vulnerable,” said Dougal.

“I put baking powder on bread. When I was young we fed seagulls baking powder on bread and watched them explode—”

“You did what?” growled Dougal.

“More water?” I shouted and jumped up to pour.

“And the dumb beasts didn’t even smell it, ate it up lickety-split,” said Mike.

Amy dropped her utensils and cleared her throat. Dougal put his hand over his mouth. Muzzled for now, I thought gratefully. What could anyone of us say? This was beyond anything I’d ever expected from him. I got up to remove the tray of chicken wings on the counter and placed it between Mike and Dougal. Throw them a bone.

Dougal snapped the cartilage off the end of a wing. Mike tore his in half and sucked meat off the ulna.

“The next time they come to the dumpster I’ll—”

“What? Tell us what you’ll do,” barked Dougal.

Amy threw her napkin at him. I felt helpless in the face of this square off.

“Excuse us,” I said. In the kitchen, scraping plates Amy apologized and said she didn’t know he did these things. I wondered, really, what she saw in him. Amy asked where the washroom was.

“Upstairs, end of the hall,” I said and took the forks from her. I couldn’t wait for the evening to end. I regretted inviting them—him. I peeped out from the kitchen. Dougal and Mike were in the living room. Mike had turned on the hockey game. Dougal sat on the edge of the sofa staring at Mike in bewilderment. Soon Mike would shout out for beer and chips and there’d be no getting rid of him. I loaded the dishwasher and heard the girls in the basement playing with the dog; she let out a series of lazy barks that signified her contentment. I put the kettle on and set a tray with pickles, cheese, pretzels and a party mix of chips.

Where was Amy? Gone for almost twenty minutes. I ascended the carpeted stairs. The bathroom door was ajar and the light still on. I had an awful feeling of disgust rise. Was she snooping in my bedroom? Was she looking at the things I kept on my nightstand? My journal? Our wedding photo? The dried rose petals I kept between the pages of my poetry book, the Pablo Neruda that Dougal gave me for Valentine’s Day last year? Was she in the en-suite? Looking through our creams and ointments, our condoms and contraceptive foam? Would she be shocked to see that I did not welcome pregnancy? Actively tried to prevent it?

I burst in my room, expecting to see her bent over a drawer picking through my underthings but the light was off and nothing was disturbed. I glanced toward the washroom. Again, no lights were on. And no sign of Amy.

I stood on top of the stair landing, convinced I’d simply missed her, she might be out in the backyard, or had run out to her car, or joined the girls in the basement. Halfway down the stairs I noticed the girls’ bedroom lights were on. How many times had I told them to turn out the lights? I poked my head in and turned off the light. I opened the door and turned on the mini-fan to circulate air. I went to my youngest daughter’s smaller bedroom to do the same. And there she was: curled up on my daughter’s bed, a pink floral shaped pillow clutched in her arms. Her eyes were closed and she was stroking the pillow and smiling. She looked odd in the semi-darkness, bluish winter light long gone; navy blue sky casting a gloom over the room, made more eerie by her body, a stony grey figure lying in a rumpled heap.

“What are you doing in here?” I asked. Sharpness that I hadn’t quite intended, but couldn’t deny, pierced my tone.

“Nothing,” said Amy and sat up and stretched, “only enjoying the—“

The what? Smell? Pink polka-dot bedspread? It was unacceptable that she was in here. I hadn’t showed her any of these rooms yet. And when you enter someone else’s house surely the tour comes before the lay-down? Was it just me? Had she crossed the line? Now I was wondering if she might be just a little disturbed. This seemed beyond the parameters of rudeness.

“—quiet. I needed some alone time,” said Amy.

I softened. That seemed plausible. After all we’d just endured dinner with her husband. I don’t know how she did it every night.

“Why didn’t you say so? I could have let you use my bed.”

“This one was closest to the bathroom. I got a sudden pulsing headache in there. What kind of lighting you got in there anyway, so strong,” said Amy.

When she sat up pink fabric poked out the front pocket of her hooded sweater. I saw the silver clasps and the gingham trim. It was my daughter’s pink polka-dot onesie, the one she wore the day we adopted our golden lab from the shelter. She was eighteen-months old. I kept those in a box in the closet. On the top shelf.

Disbelief contorted my brow.

“Relax. You don’t need it do you?” said Amy and stuffed it deeper in her pocket.

She walked past, strode down the stairs, head raised haughtily, looking back—and one look was enough—unapologetic with a small smile of triumph and unabashed entitlement brandished across that skinny, spotty, smug face. I remained in the kitchen for the rest of the night. Summoned to the living room only to refill the platter of food or dispense cold beer. She didn’t look at me. Not once. She cracked nuts and jokes with my slightly drunk husband whose social remoteness softened while under the influence, when even the worst cretin in the room was invited into his sphere of comradery. I’d deal with him later.

I coaxed the girls to bed. Put the dog on her cushion in our room and crawled under the sheets myself. In the distance their voices folded in on one another. Bursts of laughter kept me awake just as I was on the cusp of sleep, until all was silent and I slept.

-

After wiping down the Keurig I brought Dougal his coffee. I found him in the alcove on the computer searching for dog leashes. The phone rang. I saw that it was her. I ignored it.

“I feel for her,” I said to Dougal who was distracted by a selection of retractable leashes.

“Why?”

“Because she’s having so much trouble conceiving, I can’t imagine life without our girls.”

“Some people don’t make good parents,” Dougal said.

I was about to say, How would you know? You don’t really know her. She might be excellent with children, but the girls had just come home, I could hear them arguing in the vestibule over the last coat hanger.

She sent me a text later that day and several more for weeks after that. I’d stopped answering her. Hadn’t answered an email until she sent one, after many—too many?— that had implored me to contact her, filled with questions like Where are you? Are you ok? And the final one, If you don’t answer me I’ll call the police to which I responded with, I’m fine. But I don’t think we can be friends.

And that was it. The last I heard from her.

On a snowy Sunday morning in November I bundled up and left, nowhere-bound, in need of solitude after a long night of battling a flu that had infiltrated the household. Numbness in my gums as clumps of snow driven by a sharp wind pummelled my face. I must have walked for an hour, slush washing over my boots, dampening old salt stains in the shape of a wave, when I found myself circling back to town. I walked along the edge of the Falls.

At the bottom of the Bridal Veil Falls, on the American side, frozen sections of ice lay around the chunky bedrock. Sheets of it inched down the side, frozen in cascading layers. In the distance teenagers climbed cliffs close to the pedestrian bridge. Mist lolled over Horseshoe Falls—as thunderous as ever—and piped up the crest. I breathed in deeply, refreshed by its presence.

I trudged back up the hill, lonely without my family, a stiff cold settling in my bones. I’d have a coffee and then I’d head home. I walked along Clifton Hill Road, a crowded street with the ghoul, adventure and gaming shops, and went in the Tim Hortons near the fudge shop. I drank my coffee and watched the Niagara SkyWheel, a modern attraction, larger than a Ferris wheel with enclosed gondolas, standing one hundred and seventy five feet—the highest observational point in the area—out the window. Despite how many, if any, people were inside it was always moving, oblivious to the presence of occupants. It was cold, so of course no one was in line. This was tourist territory.

On impulse I swallowed the last of my coffee, went out the back door and bought myself a ticket for the ride. Inside the heated cabin a muffled, high-pitched instrumental version of the Beatles song “In My Life” played. I turned on my iPod to drown out the sound. A husky-voiced reporter on NPR announced an Amber Alert for Niagara Falls. It involved a Target clerk who’d taken another woman’s baby. Witnesses say she offered to watch the baby while the mother tried on a dress. Identity of the suspect has not yet been confirmed.

Had she taken someone else’s baby? If so, would the baby be in a car-seat or in the trunk? A precious pearl hidden in layers of cloth, choking on exhaust fumes in the dark, alone, fretting for her mother’s breast milk? Was Amy capable of going that far to get something she wanted?

I didn’t know. I googled everything I could about the Amber Alert. I didn’t find out anything new. There was a woman on the loose with a stolen baby. That was clear.

In the last go-round the wheel stopped to unload passengers. I was still high enough to see the entire expanse of the falls and everything else—parks, the lights of Clifton Hill and brash casino towers. Rainbow coloured lights over Horseshoe Falls, blazing, flashy and loud, inadvertently cheapened the natural landscape; silence and drudgery and grey machinery on the American side. I watched the row of cars, exhaust and fumes shrouding the fleet of foot traffic along the Rainbow Bridge. Was Amy there in the scrum, her car one in a line of nondescript vehicles crossing the border on a Saturday night?

When the wheel brought me down I walked home. Drained, empty of will and strength, frightened too, about what she might have done to my girls if she’d had the chance. I’d find out soon enough if it was her. Part of me didn’t want to know.

Walking along the edge of Niagara River all the way to the hydroelectric plant and stopped near the mess of wires and cables and grey buildings and thought back to the afternoon we’d spent at Lilydale. The bus had dropped us off and we walked the few blocks back to her house.

What if he really doesn’t want to have a child?

He says he does, doesn’t he?

Yes, but what if he’s just saying that to please me?

There are ways around a man’s reluctance, I said slyly.

Yes, but I don’t know if I can be so deceitful.

She was an honest woman at heart. She couldn’t even manipulate that slum-dog husband of hers into giving her what she wanted most. (Apparently it wasn’t a case of low sperm-count on his part or an inhospitable womb on hers – or any other assorted afflictions or malfunctions; all was in order in that respect). Desperate times and all that, call for actions that seem like the best solution when you’re fed up, pushed to the wall, and have exhausted all other, sane, peaceable options.

Suddenly she’d blurted out, That woman’s art, the water, its contamination, do you think it has affected generations of us women? Made it impossible to conceive? I thought of the toxins, entities unto themselves, with purposes I couldn’t fathom, surging through the water, falling over the falls, particles clotting in the mist above. I had no idea if they were related. There are things I’ll never know.

I was amazed that she’d taken it to heart. I wasn’t sure if what the artist had created for sociological posterity, turning scientific reports into art, was to blame. It fed Amy’s conflict. Her struggle between spirit and matter, her pleas, prayers and supplications, attempts at overcoming knowledge from local legends that disturbed her mind and body, leading her to look towards the unseen for answers.

Amy, you’re overreacting, was all I’d said.

Her misty tear-swollen eyes, not a drop escaping out of the bloated sac of her eyelid, looked forward as that American resolve, like an eel swimming, stirring itself in a current of static, ready to snipe at anyone who got in her way, made her bark out in a flush of anger, Candace, don’t tell me how I should feel. You don’t know me at all.

___________________________________________________

Dayle Furlong is a poet, novelist, and short story writer from Newfoundland. She studied Creative Writing at Humber College and Literature and Fine Arts at York University. Her novel, Saltwater Cowboys, was a Toronto Public Library Dewey Diva Pick and her poetry has been described as “reminiscent of seventies feminist-Atwood” by George Elliot Clarke. Furlong currently lives in Toronto.