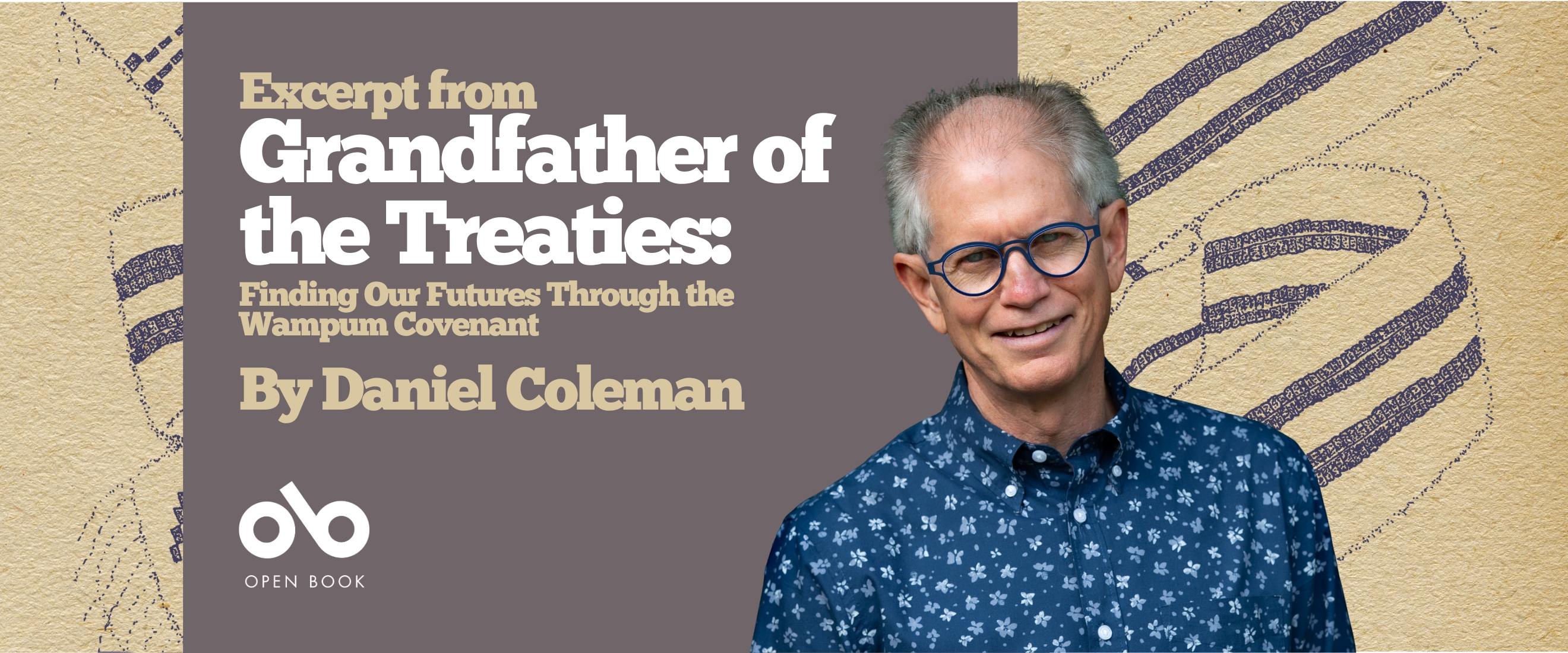

Read an Excerpt from Grandfather of the Treaties by Daniel Coleman

A longstanding academic and scholar, Daniel Coleman arrive at his office at McMaster University one morning to find the place full of police officers. He soon found out that they had been offered lodging there as they raided Indigenous lands near the town of Caledonia, during the dispute between Six Nations of the Grand River and the Government of Canada. Until then, Coleman had not fully understood how pervasive these breaches in treaty rights and the occupation of Indigenous lands were, and that broken relationships such as this were part of everyday life in Canada.

As a result, Coleman doubled-down on his existing empathy for Indigenous rights, and dedicated himself to work with scholars who could more fully illuminate the many problems that have corrupted relationships between Indigenous nations and governments throughout Canada. His aim was to explore ways that these breaks could be repaired, and he found a possible blueprint for such progress in the founding wampum covenants that the earliest European settlers made with the Haudenosaunee nation.

In Grandfather of the Treaties: Finding Our Future Through the Wampum Covenant, the author focuses on these historic agreements, and how they have been irresponsibly ignored in recent centuries. And, he examines the pathways to healing and social progress that these covenants still contain.

We're thrilled to share this fascinating passage from this new nonfiction title, in advance of its release. Free for all of our fine Open Book readers!

An Excerpt from Grandfather of the Treaties: Finding Our Future Through the Wampum Covenant

There’s a church six and a half blocks from my house. It’s called “Canadian Martyrs Catholic Church.” Right beside it is Canadian Martyrs Catholic Elementary School.

I’m not Catholic, but in my Grade 10 public school class in Canadian history, I was taught about the Canadian martyrs. The first people declared saints in North America were the five Jesuits killed by the alliance of Peoples the French referred to as the “Iroquois” in the 1640s.

The story of the Canadian martyrs is one of Canada’s more sensational stories of origin. It’s a story that tells of saintly priests and peaceful newcomers braving brutal savagery on their way to building homes, churches and civilization. It wasn’t until I moved to Hamilton, Ontario, six and a half blocks from Canadian Martyrs Catholic Church, that I heard a different side of that same story. The people the Jesuits called “Iroquois” have a reserve just half an hour’s drive south of here on the Grand River territory. Long before their ancestors met the Jesuits, they had formed an alliance of nations around a message of peace. They called themselves “Haudenosaunee,” meaning “they are building the longhouse,” and their social-political longhouse was made up of the Kanyen’keháka (Mohawk), On^yote?a:ka (Oneida), Onoñda’gega’ (Onondaga), Gayogohó:no (Cayuga) and Onödowa’ga:’ (Seneca) nations. They lived in the region of the Finger Lakes in what is today upstate New York. The rivalry between the Huron-Wendat-Algonquin alliance, who traded furs with the French generally north of the Great Lakes, and the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, who traded with the Dutch and the English mostly south of the Lakes, escalated in the 1600s from occasional raids to open warfare as the rivalling European traders supplied arms to their Indigenous allies.

The story of the Canadian martyrs emerges out of that trade in arms and souls and furs. Like many action-adventure stories, it centres on violence, a story of innocent people attacked by savages, a story that troubles the heart and excites the mind. It’s one of many such stories that energize colonial history.

There are, however, other stories. Since moving to live near Six Nations, I’ve heard the stories of how people in this exact region and time period made peace and lived in highly organized societies guided by sophisticated civil institutions. These stories do not get told as often in colonial history. They’re rarely told in high school classes. Most Canadians have not heard them. Nonetheless, there is a stream of stories about Indigenous envoys stepping courageously toward unknown newcomers, carrying the articles of peace. This is a stream of stories about cross-cultural, inter-national peacemaking that have never truly ceased. They are stories that feed what Haudenosaunee People call “the Good Mind.”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

This book aims to retell these widely neglected stories of the Good Mind.

Let me begin with one recorded by the Jesuits themselves:

Kiotsaeton’s Peace Mission

On July 5, 1645, several vessels shimmered through the heat haze toward the shoreline at Trois-Rivières. There, the Jesuits had a mission frequented by French settlers and soldiers, as well as their Huron-Wendat, Montagnais (Innu) and Algonquin allies. When they saw the vessels approaching, the inhabitants rushed to the landing place to throw their arms around the neck of a long-lost villager, Guillaume Couture, who had been taken prisoner by the Kanyen’keháka along with Jesuit Father Isaac Jogues almost three years earlier. While Jogues had escaped with the help of the Dutch commissioner of trade, Arent van Curler, down on the Mohawk River, Couture had remained with the Mohawks and was only now being returned in exchange for a couple of Haudenosaunee prisoners.

This event constitutes a fragile moment when enemies took a breath and tried to create peace, a space for dialogue, in the spiral of violence. An Algonquin party of warriors had killed eleven Haudenosaunee warriors the year before. But they had spared one of the Haudenosaunee from their hatchets. They turned him over to their French allies, who had loaded him with gifts and letters anxiously proposing peace and sent him back to his home, hoping these gestures might avoid reprisals of war clubs and fire. In response to these gestures, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy had delegated a tall, gifted orator named Kiotsaeton to lead a peace embassy up the freshwater river from Mohawk country, past the lake the French named after Champlain, overland into the big river they named St. Laurent, then down the increasingly salty water to the enemy mission where the three rivers met.

As the boats neared the shore, the tall Kanyen’keháka leader stood in the bow of his canoe.

__________________________________

Daniel Coleman is a recently retired English professor who is grateful to live in the traditional territories of the Haudenosaunee and Anishinaabe in Hamilton, Ontario. He taught in the Department of English and Cultural Studies at McMaster University. He has studied and written about Canadian Literature, whiteness, the literatures of Indigeneity and diaspora, the cultural politics of reading, and wampum, the form of literacy-ceremony-communication-law that was invented by the people who inhabited the Great Lakes–St. Lawrence–Hudson River Watershed before Europeans arrived on Turtle Island.

Daniel has long been fascinated by the poetic power of narrative arts to generate a sense of place and community, critical social engagement and mindfulness, and especially wonder. Although he has committed considerable effort to learning in and from the natural world, he is still a bookish person who loves the learning that is essential to writing. He has published numerous academic and creative non-fiction books as an author and as an editor. His books include Masculine Migrations (1998), The Scent of Eucalyptus (2003), White Civility (2006; winner of the Raymond Klibansky Prize), In Bed with the Word (2009) and Yardwork: A Biography of an Urban Place (2017, shortlisted for the RBC Taylor Prize).