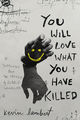

Read an Excerpt from Kevin Lambert's You Will Love What You Have Killed

In You Will Love What You Have Killed (Biblioasis), the debut novel from Quebec author Kevin Lambert, past wrongs are not forgotten, and life-long debts are paid with blood.

In Lambert's fictional rendering of Chicoutimi, Quebec, there are no shortage of strange characters: the old man who is convinced he's already died, the witch who gathers storm clouds against her enemies, the grandfather who fashions slippers out of the recently-departed family dog. When children in the town begin dying violent deaths, however, one man (coincidentally also named Kevin Lambert) always seems to be close to the tragedy. Unbeknownst to the adults of Chicoutimi, their small victims don't feel much like resting in the ground. Rising from their graves to attend school, grow, and mature, they keep a watchful eye on the adults that live among them, biding their time until they can unleash an earth-razing campaign of revenge.

Translated from the French by Donald Winkler, You Will Love What You Have Killed is a deliciously twisted and blackly humorous tale of vengeance that cements Lambert as a powerful and wholly unique new voice in Canadian literature.

We're very excited to present an excerpt from the novel on Open Book today.

Excerpt from You Will Love What You Have Killed by Kevin Lambert:

MACHINES MURDER CHILDHOOD

Kevin is on his way back to the Rue des Tourterelles aboard his deafening monster, speeding through Des Oiseaux: the machine’s metal squeals loudly when the snowplow passes over a hole in the frozen asphalt. He’s well into his twenties but looks sixteen, he reminds you of those teenagers on television sitcoms played by actors who are much too old, you tell them to drop their pants below their bums, put their hats on backwards, you give them skateboards so they seem to have come “right out of high school.” You can sense Kevin’s hairless chest under the jacket he’s wearing in the truck’s heated cab, it feels like a furnace in there, but he’s kept his toque on to free his face from his long blond hair. Before starting work he lights a cigarette, looks at the big pile of snow he has to clear, an iceberg in the middle of the street, it’s dangerous, it will block the road when people are leaving for work or coming through the traffic circle. Kevin doesn’t know that in a few minutes little Sylvie, buried there, will be torn to pieces by the blower’s sharp-edged screw, turning over mechanically on itself, gobbling everything in its path. Sylvie is buried in the snow and it’s a real shame: children do not always have the wisdom to respect even simple instructions. Even if she knows she lives at 2008 Rue des Tourterelles, that her right hand is on the right, her left on the left, that she’s lefthanded and that in her grandmother’s time left-handed people were shut up in cages beside the road and left there to be eaten by horrible black crows, that you mustn’t take candies from strangers, not say “Marie noire” three times in front of the mirror, that you have to listen to Viviane when she tells you to go to bed, that you must never tell the truth on the internet, even on the game sites where you’ve made a friend, because this friend is certainly an old man who wants to do all sorts of things to you that you can’t talk about at school, even if Sylvie knows all that, excited as she is by the snowfall, she may have forgotten that you must never tunnel into a snowbank.

Sylvie’s tunnel is exquisite. She’s dug it right at the bottom of the pile, and it goes in deep. Her idea was to cross through it from one side to the other. But her architectural skills are limited, and it collapses as soon as she enters it. Sylvie is trapped, stunned by the weight of the snow dropping so heavily onto her little body that’s cocooned in a thick snowsuit. She tries to move, but she can’t, she cries with her little voice, snow is weighing on her mouth, her nose, her eyes, her entire body, it’s cold, she turns on one side then the other, she tries to dig herself a path, push away a bit of snow, she manages to find a little hole for her face where she can breathe without swallowing ice. She is able to cry a little bit louder, but around the traffic circle nothing can be heard but the low-pitched growling of the snow blower. The packed snow smothers the little high-pitched sound Sylvie is making. Her hands are trapped under her body, her thumb is twisted inside her mitten, she tries to turn her head, she tries with all her strength to move her feet, but the snow is too heavy.

The snow blower is coming, Sylvie, you’d better move. Do you hear the machine? Maybe you think it will take away the snow and you’ll be able to escape. You hear the blower turning, sucking up the snow to spit it out farther on, into the centre of the traffic circle, near the street lamp: you’re afraid. You cry, you cry some more, you yell, and your little tears run down your cheeks. It’s dark. You swallow snow when you open your mouth to cry out your distress, but all your sounds are smothered, they don’t reach past the hard lumps that are holding you down in the depths of Chicoutimi. You don’t know what to do, you’re suffocating, you push with all your body, but nothing moves, you’re angry, desperate, deafened by the growling motor, the mechanical shovel. Its pistons are making the whole street shake, are pounding the ice-hardened ground. Exhausted by your efforts, you grow calm for a moment. It’s there, Chicoutimi, everywhere around you, it has swallowed you up in its snow. Think, you have to get out of this fix, otherwise you’ll never have the two dollars for the tooth you lost this morning that’s sleeping on your pillow. Cry, Sylvie, cry that you want to see your papa and mama again, your little cat and the Mickey Mouse posters in your bedroom, howl that you want to be babysat again by Viviane. Hammer this black snow with your feet as hard as you can, fend off the cruel mechanics of the snow blower, insist that it’s not its decision to make. The pitiless snow is obliterating you, Sylvie. You give a few feeble kicks, then you stop, frozen stiff by winter. Out of strength, of breath, of courage, your voice is lost beneath the grumbling of the snow blower, beneath the heavy layer of snow. In despair, you murmur, “Marie noire” three times. You hope to call up a spirit, an avenging ghost, a soul in pain, you want to sell yourself to the devil for the rest of your life, if only to carry on a little bit longer. Even the evil spirits have abandoned you. The blower spits out a brief jet of scarlet snow, with Sylvie pulverized inside it, onto the snowbank.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Soon the whole city will learn of your death. Your mother will weep for a long time, will break her favourite knick-knacks and her prettiest framed photos of you. Your coffin will be buried in the Chicoutimi cemetery. On your grave will be carved a little Mickey to remind you of the posters in your bedroom. And the vile toads will come, every night, to sing in your memory.

THE DEATH OF THE NOTEBOOK

On Monday morning, in the residential neighbourhood, Sylvie is at every family’s breakfast table. You see her mirrored in cups of cold coffee, on the front page of Le Quotidien, in the children’s cereal scattered about, you hear her crying through the hairdryer’s din. You go to school, to the office, and at a street corner or a traffic circle, seeing a snow blower in action, you wonder if it’s there that the accident happened. Her blood is leaking out still. It stains my notebook with its perfectly round, perfectly red drops, falling onto blank pages in our grade two classroom, where I miss her, my friend by default. She and the cat, I draw them with a felt pen or in watercolour, a big red blot bursting onto the body of a little girl, a cat all blue and stiff, frozen into shiny powder glued onto the page. It’s “my project,” pinned up for a few weeks in the administration hallways along with all the other class drawings and the banner WE WON’T FORGET YOU SYLVIE FORCIER, in honour of our dead friend. I wonder if Sylvie still exists. I’m troubled by the question of her body. I want to know if the status of a dead person is changed when the body is utterly pulverized. Her blood is still mixed in with the watercolour on absorbent paper, pinned up in the administration’s corridor. It’s the first time I have gone to the end of that hallway. I didn’t know what was behind the closed door at the very end, with no window to see inside: a room where you closet Sylvie’s parents, my mother, Viviane—who seems to be the most shaken by the tragedy—and me, to do psychology on our brains and make sure that we won’t go right out and hang ourselves. It seems like this will be hardest of all for my mother.

Sylvie has already been back to school for several weeks. It’s very strange for us, in the midst of mourning our friend, to see her again one morning sitting alone in the empty classroom, there before everyone else. Sylvie carries on as if nothing has happened. The yellow cardboard with her name on it has been thrown away, she makes another one during our math lesson. She also, like all the students, makes a drawing in her own memory so it can be put up in the corridor. Sylvie draws herself dead beside the big snowplow, even if, despite her tragic demise, she’s still among us.

____________________________________

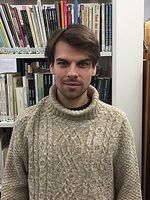

Kevin Lambert is a Quebec writer born in 1992. He grew up in Chicoutimi in the Saguenay – Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec. He graduated from the University of Montreal with a master's degree in creative writing and is currently pursuing his doctorate in creative writing