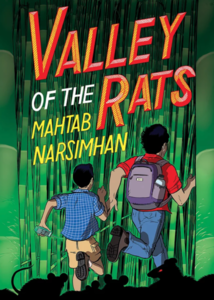

Read an Excerpt from Mahtab Narsimhan's Valley of the Rats, the Story of a Father and Son Lost in a Mysterious Bamboo Forest

Krish has no interest in getting dragged around outside, camping and exploring and muddling in who-knows-what kind of germs. He's much rather stay inside with a good book, but his photographer father Kabir has other ideas. He drags Krish along on an epic camping trip, convinced it will help them bond and forget their differences.

Deep in the bamboo forests of Ladakh, in Kashmir, India, father and son do their best to find common ground. But soon that's not all they're looking for when they realize they're hopelessly lost.

We're excited to present an excerpt from the rollicking adventure that is Valley of the Rats (Dancing Cat Books), the new middle grade novel from award winning author Mahtab Narsimhan.

Valley of the Rats follows Krish and Kabir's journeys, both literal and emotional. Funny, smart, and packed with surprises, it's Narsimhan doing what she does so well, with tight storytelling, compelling and relatable characters, and secrets that become dangerous obstacles.

In this section of the novel, we see Krish and Kabir meet two mysterious strangers when they're lost and hungry. They're allowed to stay and rest in a very odd village that isn't marked on any of their maps, but they have no idea what's to come.

Excerpt from Valley of the Rats by Mahtab Narsimhan:

“Stop!” said a voice from the darkness. “What are you doing here?”

We froze. I looked around but saw no one, though a smell of wet animal hung in the air. Was it the guy who’d told me to run playing games with us again? Despite the exhaustion, I was ready to give him a telling-off if he showed himself. Enough already.

“We’re lost,” Dad said. “Can you please help us?” I was surprised at how calm and confident he sounded.

A lantern wick glowed bright. My gaze travelled up the hairy hand holding the lantern, to a man’s face. It was thin with a long nose and weak chin. His front teeth protruded between gray lips, and his large ears twitched as if listening to something I couldn’t hear. It was the red eyes that bothered me the most. Conjunctivitis? I took a step back.

“Namaste,” said Dad.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

“You should not be here,” said the man, sternly.

“You got that right,” I said. “This was a huge mistake.”

Dad dug his fingers into my shoulder. I got the hint.

“My name is Kabir Roy, and this is my son, Krish. As I mentioned before, we got lost during a camping trip. Our GPS isn’t working, nor are the radio and cellphone. If you could let us spend the night here and allow us to use your telephone, we’ll call for help and be on our way. We would be happy to pay you for boarding and food.”

The weird man continued to stare at us. An icy blast swept into the valley. I shivered and sneezed, spraying the villager full on. “Sorry,” I said, wiping my sleeve across my nose. “I’m freezing.”

Still the man said nothing.

“So, can you provide us shelter for the night?” asked Dad, his voice tinged with impatience.

“Please,” I added. “We’re cold and tired and very hungry.” I hugged myself tight as the wind sliced through me, causing me to sneeze three times in succession. “And something or someone is following us. Don’t send us away.” I was willing to beg if need be.

The villager’s face softened. “We know what it is to be cold and hungry.” He put the lantern on the ground, took off his black fur coat, and draped it over my shoulders. It smelled strange, but was so warm, it felt as if I were slipping into a hot bath. My nose lost the battle against my body as heat spread through me from head to toe.

“Thank you, sir —” I said, pulling the coat tight around me.

“Dorje,” he said. “We do not encourage travelers to stop at our village, but it is not safe in the forest. You may stay if you follow our rules. Do you agree?”

I nodded vigorously and looked at Dad.

“Yes, thank you, Dorje,” Dad replied.

Dorje turned and hurried on a well-trodden path toward the village. Tonight, we would sleep on a bed, eat hot food, and probably have a chance to bathe.

Felicitations.

We walked across the wide clearing I’d seen while we were descending. Firelight flickered inside the huts and seeped through closed shutters. Close to the ground, shadows moved. The village was infested with rats. I’d educate Dorje first thing tomorrow morning, even though it was these very vermin who’d helped us locate the village.

A thick grove of bamboo, higher than the ones we’d seen in the forest, grew in the middle of the clearing, like an odd centerpiece. A dozen or so villagers sat at a blazing bonfire beside the grove, talking and laughing. Lengths of blackened bamboo smoked inside the fire. I didn’t know bamboo was edible. Hopefully that wasn’t what they’d offer us for dinner.

As we hurried along, villagers in fur coats similar to the one Dorje had given me walked by, glancing at us. No one stopped us, and I was glad. It took all my willpower to put one foot in front of the other as we followed our guide. I was exhausted and in danger of passing out before we got to a bed.

Dorje stopped in front of a neat A-frame hut some distance away from the clearing. It had a large window with closed shutters. We stepped onto the wide porch and walked through wooden doors. Dorje put the lantern on the floor, and I looked around.

The hut had a packed mud floor that gave off a comforting earthy smell. A single cot, made of bamboo, sat beside the window. A table and two chairs, also of bamboo, were beside the door. A black pot-bellied stove sat in the middle of the room. It was evident that this was the source of heat, and the most important feature, so everything else was arranged around it. There was only one other door leading to the back. There was no indoor bathroom.

“This is the guest house,” said Dorje. “Stay. I will bring food and an extra cot.”

Before I could ask him about the bathroom, he was already out the door.

As soon as he left, I collapsed on the cot. Though it was chilly, this was so much better than being out in the wind. I shrugged off my backpack. Something poked my side. I remembered the crunch when I’d slipped. Did I dare look down? Would it be a broken body part that hadn’t started hurting yet?

It was the radio. Its antenna hung at an odd angle.

Fiddlesticks!

I was glad I had no broken bones, but the radio might have been our only way to call for help if the village didn’t have a land line or cellphones! Why hadn’t I given it back to Dad instead of keeping it with me?

My stomach cramped with panic, and I had to take deep breaths to calm down.

“We’ll fix the radio tomorrow,” Dad said, watching me. “I’m sure they’ll have spare parts. Don’t worry, Krish.”

Dad slid his backpack off his shoulders and put it on the floor. “At least we’ll be comfortable tonight.”

“Tomorrow we get our bearings and head back to camp, even if the radio isn’t working,” I said. “Right?”

“I wanted to talk to you about that, Krish. I’d like some pictures of this village. It’s remote and might be interesting. What say we hang around here for a day or two?”

I stared at my trembling hands, breathing deeply. Why couldn’t he see that I was miserable? Or was it that he didn’t want to see?

“What is the name of this village?” I asked. “I don’t remember seeing one marked on the map.”

Dad pulled out the map from his pocket and spread it on the floor. I knelt beside him and smoothed the corners as buttery light from the lantern spilled over it. Dad traced a finger over the route we had taken north from Leh through the Ladakh Range.

“The Adventure Camp is here,” he said. “At 34.15 degrees north and 77.57 degrees east. We walked an average of six kilometers an hour, so we should be here: approximately 36 north and 78 east. This is where the village is.” His finger stabbed a spot on the map.

“There’s nothing marked here but forest,” I said, frowning.

Dad looked up at me, his eyes sparkling. “Exactly! Do you realize the opportunity we have? This is a photographer’s dream!”

And his son’s nightmare.

The door creaked open, and Dorje appeared with a girl who looked to be about my age. The girl carried a tray, and Dorje brought a burning log in a pail. She nodded at us and set the tray down on the table while Dorje headed for the stove.

“This is Tashi,” said Dorje, starting to light a fire. He added logs from a pile by the door. “Our shaman’s daughter.”

“Hello,” I said, unable to stop staring. A large red birthmark covered a side of Tashi’s face, vivid against her white skin and silver hair. Her eyes, a light gray, looked cold. She made me uneasy.

Tashi arranged two pieces of charred bamboo, about ten inches in length, and two cups of steaming liquid on the table, and glanced at me. “Obviously you haven’t met too many albinos,” she said.

I blushed, looking away immediately. She was right: I’d never met an albino. But I should have known better than to stare at her. “Sorry,” I mumbled.

“I forgive you,” she said, lifting her chin slightly. “We’re rare and quite special.”

In that very instant, I liked her. She was different, and she owned it.

“I guess you don’t like travelers in your village, right?” I said.

“Only if they —” Tashi started to say.

A volley of sharp clicks spilled from Dorje’s mouth. Tashi shut up instantly. He’d said something in that click tongue so we wouldn’t understand. Dad and I stared at him, hoping he would explain or translate. He didn’t. An awkward minute crawled by. Tashi held my gaze silently. I got the feeling she wanted to say something, but not in front of Dorje. I was terrible at physical activities but great at reading silences and looks. This one spoke volumes.

“What is this village, Dorje?” asked Dad, peering at the map spread out on the floor.

Good job changing the subject, Dad.

“Imdur,” Dorje replied, shutting the stove door with a clang. Sparks leaped through the grate as the logs caught fire and blazed. The smell of woodsmoke filled the room.

“Why can’t I find it?” said Dad, his grimy finger still on the map.

Dorje’s eyes bored into us; they were like black mirrors reflecting twin flames. “Because we don’t want to be found.”

__________________________________________________________________

Excerpt from Valley of the Rats by Mahtab Narsimhan, a middle-grade novel published by DCB, an imprint of Cormorant Books. Copyright 2021, Mahtab Narsimhan. Reprinted with permission.

Mahtab Narsimhan is the author of a young adult trilogy, four middle-grade novels, and two picture books. Her first novel, The Third Eye, won the Silver Birch Award. Its sequels, The Silver Anklet and The Deadly Conch, have received critical acclaim, and Narsimhan’s standalone novel The Tiffin, was nominated for the Red Maple Fiction Award, the Manitoba Young Readers’ Choice Award and the SYRCA Snow Willow Award. A native of Mumbai (Bombay), Narsimhan now lives in British Columbia.