Read an Excerpt from THE SEASIDE CAFÉ METROPOLIS, the Highly Anticipated New Novel from Antanas Sileika

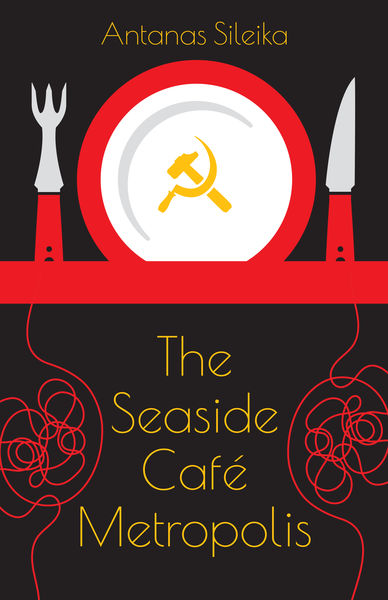

In his brilliantly comic and deeply human new novel The Seaside Café Metropolis (Cormorant Books), widely celebrated author Antanas Sileika invites readers into the absurd, tender, and truth-filled world of Cold War Lithuania. It is the 1950s, and Canadian restaurateur Emmet Argentine finds himself stranded in Soviet Vilnius under the watchful eyes of bureaucrats, spies, and his unrelenting socialist mother. What begins as a tale of political misadventure quickly becomes a celebration of resilience, humour, and the small freedoms that thrive even in the unlikeliest places.

Raised in the kitchens of Toronto’s grand Royal York Hotel, Emmet’s gift for hospitality lands him an improbable post running the dazzling new Seaside Café Metropolis—a restaurant that is neither seaside nor metropolitan. Soon, this culinary haven becomes the beating heart of the city’s underground intelligentsia, attracting artists, writers, and philosophers, as well as the occasional famous visitor, including Sartre and de Beauvoir. Beneath its glowing chandeliers and bread baskets wired with KGB microphones, Emmet and his ragtag staff serve up laughter and defiance with every meal.

With his trademark wit and warmth, Antanas Sileika captures the spirit of life under pressure, where art, food, and friendship become quiet acts of rebellion. The Seaside Café Metropolis is a feast of political satire, love, and survival. It is a story that finds joy even in the shadow of tyranny and proves that community can bloom anywhere, even in a Cold War kitchen.

We've got a delectable excerpt of this brilliant new novel to share with our readers, right here on Open Book!

An Excerpt from THE SEASIDE CAFÉ METROPOLIS by Antanas Sileika

I had never eaten fruit compote in Canada, but one adapts to local tastes. As a former resident of the land of Jell-O, who was I to judge?

Still, I actually did have to judge her performance. Each dish of compote set out on a tray on the cafeteria side of the restaurant would have sticky sides. It would leave a ring beneath it that might dry in so hard the dish could not even be lifted from the tray.

I remembered a local saying: We tried and we tried as hard as we could, yet the result ended up the way it always does.

Hopeless.

The technique, Inga, my life, and the whole damned country.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Poor Inga, broad in the chest and hips, dressed in her whites and a tall paper hat, was looking at me for support, but something in my expression must have given my thoughts away. I saw her face begin to crumple toward one of her regular crying fits. Sometimes she just could not cope when all her best intentions did not match her limitations and the Lenin Prize for Kitchen Workers remained an unattainable dream.

I was the one who should have been weeping. I would need to point out the error of her ways to the others, and then console her as she cried in my office. What she really deserved was demotion to a third-class restaurant or student lunchroom, but I was not permitted to hire or fire my staff. They were assigned to me by the party representative.

Just as I was formulating my response, she set down the ladle and bowl and licked off the back of her hand where the juice had run over it. Then she wiped her fingers on her apron.

I shuddered, and a couple of the more hygienically knowledgeable staff smirked.

My life had come to this. I’d gone from riches to rags in a few short years. I blamed my mother for my present condition. My late father too, for the effect he had had upon her. And if I was apportioning blame, why not add General Francisco Franco of Spain for being instrumental in my father’s death?

The double kitchen doors burst open, and a pair of men in grey suits waddled in as if they were penguins that owned the place. Former KGB types, it seemed, or cut from that primitive cloth. Real KGB types didn’t look like thugs anymore, and the ones that used to work for the KGB and still looked like that had to take menial jobs.

“We’re having a training session here,” I said. “No outsiders allowed

.”

“Is this the Vilnius Soviet Ministry of Agriculture’s First-Class Restaurant?”

“Bravo. You’ve found the place. The second-class cafeteria is right next door. You might like the lower prices over there.”

They looked at one another as if considering it, then turned back to me.

“Are you Emmet Argentine?”

“Brilliant.”

“Why do they call you ‘the Canadian’ if your last name is Argentine?”

“Because I’m a Canadian.”

They shrugged as if they were a pair of marionettes hung on the same string. “You are to come with us.”

My staff began to sidle ever so slightly away from me. I loved many of them and tolerated the rest, and I’m sure they felt the same about me. But solidarity is a fragile thing, and only people who live happily in the West imagine it holds true in the rest of the world. If I were being taken off to the gulag, it would not do to have been too close to me.

“The assistant deputy minister of agriculture himself is having lunch with a delegation from Smolensk this afternoon,” I said. “When do you need me to come?”

“Now.”

It was 1959, and the old days of summary nighttime arrests were past, although arrests still happened, and people tended to be nervous. True dissidents were still in jail. The gulag labour camps still had many, many unwilling residents. We did live under ty

ranny, but most citizens were now harassed in other ways.

I could have protested, but I was being saved from dealing with the tearful Inga. And stuck in Vilnius, in the Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic, I considered myself in jail already. So why should I worry even if they did turn out to be sinister government functionaries?

“I’ll get my coat.”

“We’re just going up the street.”

I insisted on getting the coat. Old-timers had told me to take as much as possible with me if I were being hustled away, just in case the short interruption turned out to be a long one. On the way out, I stuffed a few bread rolls into my coat pockets.

I told the staff to proceed with preparations for lunch and to pay special attention to the assistant deputy minister and his guests from Smolensk.

I walked out the door between the two men and onto Lenin Prospect. It was the main street of Vilnius, with the old cathedral (now a concert hall) down at one end and a miserable department store straight across the way. The store was called the Univermag. In other words, it was supposed to be a universal store, a department store that had everything, and occasionally it did have decent products, but never at the same time and never when you needed a particular item. At the moment, the store was full of baby strollers in the shape of an automobile, the Gaz M-20, a model discontinued the year before.

But real automobiles were rare. For some of the kids, that stroller might be the only chance in their lives to ride in a car that wasn’t a taxi, and those were rare enough anyway.

In the other direction, it was a long walk up the road past crumbling nineteenth-century wedding-cake buildings to a bridge that crossed the river. An old lady in a headscarf was sweeping cigarette butts off the sidewalk into the gutter, and a passing dump truck with poor ignition was blowing diesel smoke into the air. It was a weekday midmorning, so the streets were pretty empty with everyone at work.

The building they took me to was not more than a few hundred metres up the road. I’d barely paid attention to it because it had been covered by hoardings for a very long time. No more. Now I saw the new place was more or less done, a fine five-storey structure with workmen visible through the picture windows facing the sidewalk. We went in.

The front part was a café with strange triangular tables, like nothing I had seen before in the Soviet Union or anywhere else, like something out of the future. Who could imagine that a table could have only three legs? The idea must have been stolen from stools. I was surprised the tables weren’t illegal.

As we went in deeper, we passed a middle section empty of tables and chairs but with a small fountain in the centre and a standing bar off to one side. Very cool. This place was getting better and better. At the back was a very large restaurant with eight tall booths down the left side for those who wanted privacy, a stage at the end, and many more tables set throughout. Light poured in through sheer curtains from a bank of windows on my right. It was a room that could easily seat a hundred and fifty people.

This was much finer than anything I’d ever seen in Vilnius, including some of the best hotels and Communist Party dining rooms, which tended to favour red damask, gilt, and dark wainscoting. But this place had a high ceiling and impressionistic wall mosaics with a nautical theme in bright colours — sailboats and the seaside and a pair of stocky nude women sitting on the sand with their backs to the viewer as they stared out to sea.

I felt like I’d dropped into the modern world for the first time in five years, and not just any modern world. Public rooms in the Soviet Union were of three kinds — dowdy, heavy, or pompous. This place was light and airy and fresh. It felt not exactly like Toronto, but maybe better, more like New York.

My grey-suited escorts led me to an elegant man who was seated in one of the booths. He was youngish, with romantic upswept black hair greying at the temples, and his suit looked better than anything I’d seen in my Soviet time. He was smoking a BT, a Bulgarian cigarette brand, one of the better kind, hard to get. The man motioned to the grey suits, and they disappeared.

“Coffee?”

“Sure,” I said.

He nodded toward the seat across from him, and I slid into the booth.

“What is this place?” I asked.

“Welcome to the Seaside Café Metropolis. Like it?”

_________________________________

Antanas Sileika is a Canadian author of six previous books of fiction, as well as two memoirs. His collection of short stories, Buying on Time, was shortlisted for the Leacock Medal for Humour and the Toronto Book Award, and longlisted for CBC’s Canada Reads in 2016. His books have repeatedly received starred reviews from Quill & Quire and have been listed among the one hundred best books of the year in The Globe and Mail. One of his novels, Provisionally Yours, was adapted into both a feature film and a television serial in Europe. He currently lives in Toronto, Ontario.