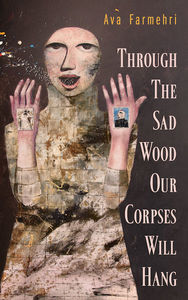

Read an Excerpt from Through the Sad Wood Our Corpses Will Hang by Ava Farmehri

On the same day in 1979 when a new, deeply orthodox government declared the birth of the Islamic Republic in Iran, Sheyda Porrouya, the narrator of Ava Farmehri's Through the Sad Wood Our Corpses Will Hang (Guernica Editions), was born.

In this repressive environment, gentle and dreamy Sheyda struggles. Sometimes erratic and often unable to differentiate between fairy tales and reality, Sheyda is confused and shocked when she is accused of killing her mother and sentenced to death.

The book follows Sheyda as she awaits either her release or her death, swinging between memories of her childhood and her grim current reality in one of Iran's most notorious prisons. Filled with beautiful imagery and intriguing clues from an unforgettable and unreliable narrator, Through the Sad Wood Our Corpses Will Hang will keep readers furiously turning pages both to find out Sheyda's fate and the truth of her conviction, and for Farmehri's lush and vibrant prose.

We're proud to present an excerpt of this remarkable book for our readers, courtesy of Guernica Editions.

An exclusive excerpt from Through the Sad Wood Our Corpses Will Hang by Ava Farmehri

When I was a child, and it wasn’t that long ago that I was, I used to look up into the sky — something I now don’t have the luxury of doing — and think about God. I used to wonder why He had chosen to reveal Himself to some men and not to others. Weren’t we all equal in His eyes? And if it is true that He had endowed His prophets with a pool of virtues inaccessible, unattainable by the rest, then why had He chosen them for such curse or honour? He created them special and then seemed to reward them for it.

We were taught these magical fables in school, and I’d sit in class mesmerized with a hand cupping my chin and with eyes fixed on my teacher’s lips, picturing the lives of these remarkable holy men — men, they were always men, I failed to notice at the time — who each seemed to have survived a childhood that struck me as strange: they were all misfits who were orphaned, unwanted, abandoned or betrayed; they were the misunderstood owners of hearts that seethed with wisdom and time that was consumed alone, in dreams or deep in meditation. They were also, initially, or eventually, dismissed as mad.

God seemed to favour loners; I thought that God surely empathized because Gods too could be lonely. And the minute I heard that story of Hayy, a thousand knots untangled in my stomach and a rope shot from my head toward the sky and connected me to all those great souls. I was one of them. I was certain that my time too would come. I was certain that God had big plans for me. My suffering was for a reason and the agony of my childhood, that exquisite sense of loss that never left me, had a purpose that would appear like a whale and retch me into the yellow arms of a shore. I was Hayy and the gobbledup Jonas; I was Joseph wrapped in the darkened echo of a well.

When on a trip to the North, my father had driven us to the shores of the Caspian, I had tossed myself scarfed and fully-clothed into the sea, and made my way through the waves on slippery weeds and rocks that kept calling my name and pulling me toward them. The water ebbed and flowed between my feet and the plastic of my red slippers until the sea withdrew and sank them like red twin boats as I helplessly watched, and the sandy bottom fled through my toes as I splashed with the frail arms of a nine-year-old the heavy waves that hit me.

My father was busy fishing, and my mother had returned to the car to bring more sandwiches and a second flask of chai. I wanted to prove my theory and conviction, that if in the midst of drowning I prayed to God, then He would rescue me just like He had rescued the kindred souls that preceded my birth. He would send His angels to lift me, or the waves would part and a big smiling whale would open his mouth and bid me enter in his belly. The whale would call me his Sheyda soup, but he’d wink at me and let me know with an

affable but moral tone that it’s all just a story, a little lesson.He’d tell me that he was God’s obedient servant and that I was really special. And then, when everyone gave up, when the search for my body faded and my parents’ tears dried on their cheeks, when dark crescents appeared beneath their hollow eyes, the whale would spit me back to safety and wave a fin as he swam away.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

There was no time for any whales to be divinely summoned, but I did have time to swallow enough water and have a quick little prayer as my legs gave way and as I slipped below the waterline. The sky blurred, the waves turned a page on my existence and I blew a shoal of white bubbles. I drifted into the bottom. It was very quiet inside, peaceful. I was deep in the sodden pockets of the Caspian. But my prayer was hastily answered when a fisherman, who had seen me thrashing in the water then disappearing under it, grabbed the hem of my blouse and dragged me out.

Back with functioning lungs and reacquainted with air, he started panting and shouting. I was both coughing and sucking air in. He carried me on his shoulder and called to my father who, thigh-deep in water and terrified, threw his fishing rod and leapt toward us, pushing against the waves with the rest of his body. I wrapped my little arms around the fisherman’s neck, smelling the saltiness of the sea and tasting the oiliness of his wet hair. I looked at the horizon where two blues merged and kissed, and then gazed up into the sky, and

knowing that God had heard me, I closed my eyes and smiled.

After wrapping me in some of my father’s clothes and leaving my own to dry in the sun, my mother held me for a long time in the car. All four doors were open and we sat in the backseat, with my head resting on my mother’s heart, and her cheek resting on my moist hair. I was shivering and had to beg them not to end our picnic, promising that I wouldn’t go near the sea again. Instead, I was sternly instructed to sit by my father’s bucket and guard the fish he had caught. I sat crying and giving them CPR, carrying each at a time in my hands, mesmerized by their rainbow scales and how, held up to the setting sun they sparkled light blue, yellow and purple.

I urgently breathed carbon dioxide back through their puckered lips, thinking that I was doing them a favour, and feeling invigorated by my act of kindness and tickled at the way they blew up like balloons with my breath, their eyes open wide. Finally I couldn’t take it anymore, and the minute my father walked away, I carried the bucket to the sea with my mother shouting after me, hobbling under the weight of five fish, which one by one I hurled into the broken waves, after kissing each and whispering a very sincere “Thank you” to the last. They slapped the face of the water then twisted back to life. Happily, I kicked the bucket with my foot and returned with a bleeding toe to my father to get spanked for throwing dinner and three-hours’ worth of effort away.

______________________________________

A passionate and dedicated writer, Ava Farmehri presently lives in Canada. But she grew up in the Middle East surrounded by books, cats and war. She loves books. She loves cats. She hates war. She really hates war. Through the Sad Wood Our Corpses Will Hang is her first published novel.