Read an Excerpt from the Unforgettable NEVER SILENT: A HIROSHIMA SURVIVOR'S STORY by Setsuko Thurlow and Kathy Lowinger

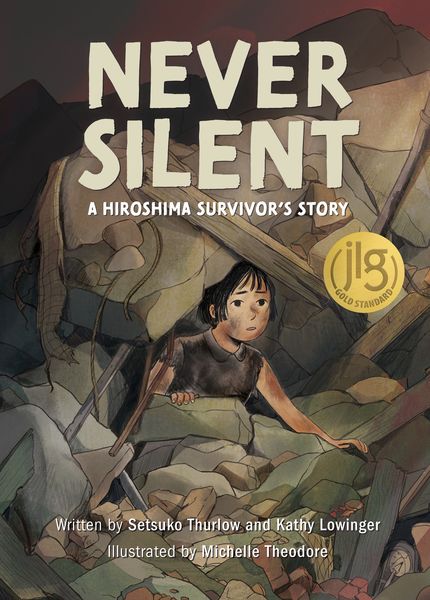

On the heels of the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, we are honoured to share an excerpt from Never Silent: A Hiroshima Survivor’s Story (Annick Press). In this powerful and deeply personal account, Setsuko Thurlow, who was just thirteen when she survived the bombing, recounts the day that changed her life and the world forever. Her story is not only a firsthand testimony of unimaginable destruction but also a moving call to action.

A lifelong peace activist and a leading voice in the global movement to abolish nuclear weapons, Setsuko’s journey, from the ruins of Hiroshima to delivering the Nobel Peace Prize acceptance speech on behalf of ICAN, serves as a testament to resilience, courage, and hope. This important work is co-written by acclaimed author, Kathy Lowinger, and accompanied by extraordinary illustrations by Michelle Theodore.

This excerpt offers a glimpse into her memories and mission, and reminds us why her voice, and others like it, must never be silent. Check it out below, and find the full book at your favourite local independent bookseller!

Everything Changes

My six brothers and sisters were much older than I was.

The gardener who tended our lovely garden became my friend, teaching me about the trees and flowers. My father was the head of the family—the clan—so relatives were always coming and going. They all doted on me, the precocious baby of the family.

Reading was my favorite thing. I read the newspapers and followed current events—there was always someone willing to answer my stream of questions.

School was easy for me. I was the only girl to get honors for each of the first six years of elementary school. From junior high on, I went to a private Christian girls’ school, Hiroshima Jogakuin, noted for teaching English and music. If you kept up your marks, you could learn to play the piano. I longed for that.

The war changed everything.

War Comes to Japan

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I can say that my childhood ended on December 8, 1941. That day, the radio announcer declared that Japan was at war with the United States and the Allied forces.

The radio announcers reminded us of our commitment to the emperor. Every day, year after year, we listened to the radio for news about the war. First would come stirring music. Then we would get reports of the battles we had won.

I was in eighth grade. Along with about thirty girls from my school, I was given special training to help decode messages from the front lines. It was complicated work. You had to add and subtract quickly and check the code books fast without making any mistakes. It shows how desperate Japan was that schoolgirls were put in charge of such important work. What we didn’t know was that the Americans had broken the codes.

As summer wore on, everyone was tense. Other cities had been bombed. Why not Hiroshima?

A Silent Flash

The evening of Sunday, August 5, 1945, my older sister Ayako and her four- year-old son Eiji arrived in Hiroshima. They had come to town so Ayako could see a doctor about a problem with her eye. There was more food in the countryside, and she’d made and brought with her my mother’s favorite dish of red bean paste in sticky rice. We had afternoon tea together in the sunny garden and enjoyed the rare treat. My father was annoyed that Ayako had come and wanted her to go back to the safety of her country home.

The usual air raid sirens blared throughout the night, but next morning the all clear was sounded. I got up at 6:30 a.m. to get ready for my first official day of work as a decoder.

The blue summer sky was cloudless. I walked to the railway station to meet my classmates. I was the leader of the group. We formed ranks. I gave the order—“Quick march”—and we paraded off to the army headquarters, a big wooden building about one and a half kilometers (one mile) from the center of Hiroshima.

At the door, we saluted the sentry. Major Yanai was in charge of the coding operations. We followed him to a large room on the second floor. He told us, “Girls, this is the way we dedicate our work to the emperor. Do your best!” Just as we replied, “Yes, we will do our best,” the entire window filled with a blinding bluish-white flash.

Miles outside the city, people heard a thunderous roar, but I heard no explosion. There was just that silent flash. Together with the building, I was falling. I was knocked unconscious. When I came to, I found myself in darkness, buried under the debris of the collapsed building. I thought a bomb had dropped right on me.

I couldn’t move. Though I knew I was facing death, all I felt was a strange calm. I heard the faint voices of the other girls whimpering, “Help me, Mother. I’m here. Help me, God.”

Suddenly, someone’s strong hand was shaking my shoulder. Then hands were loosening the timbers around me. I heard a man’s voice. “Don’t give up, keep pushing, keep moving.” There was a glimmer of light to my left. The man said, “Don’t give up. I’m trying to free you. You see the sunlight in the opening? Crawl toward it as quick as you can.” I crawled out of the darkness.

_____________________________________________

Setsuko Thurlow was thirteen years old when the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the city she grew up in. Setsuko survived the blast, but that event shaped her life, as she worked tirelessly to make sure that no one would ever again experience that horrific event. Setsuko has devoted her adult life to campaigning for nuclear disarmament, working with the organization ICAN, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, the recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2017. Setsuko lives in Toronto, Canada.

Kathy Lowinger is the author of many award-winning children’s books, including What the Eagle Sees, Sky Wolf’s Call, Turtle Island and Ours to Tell. She lives in Toronto, Canada.

Michelle Theodore is an illustrator born and raised under the prairie skies in Edmonton, Alberta. As a landlocked yonsei, she is often reminiscing about coastal summers with family, inspired by her times on beaches collecting sand dollars and eating homemade salmon jerky.