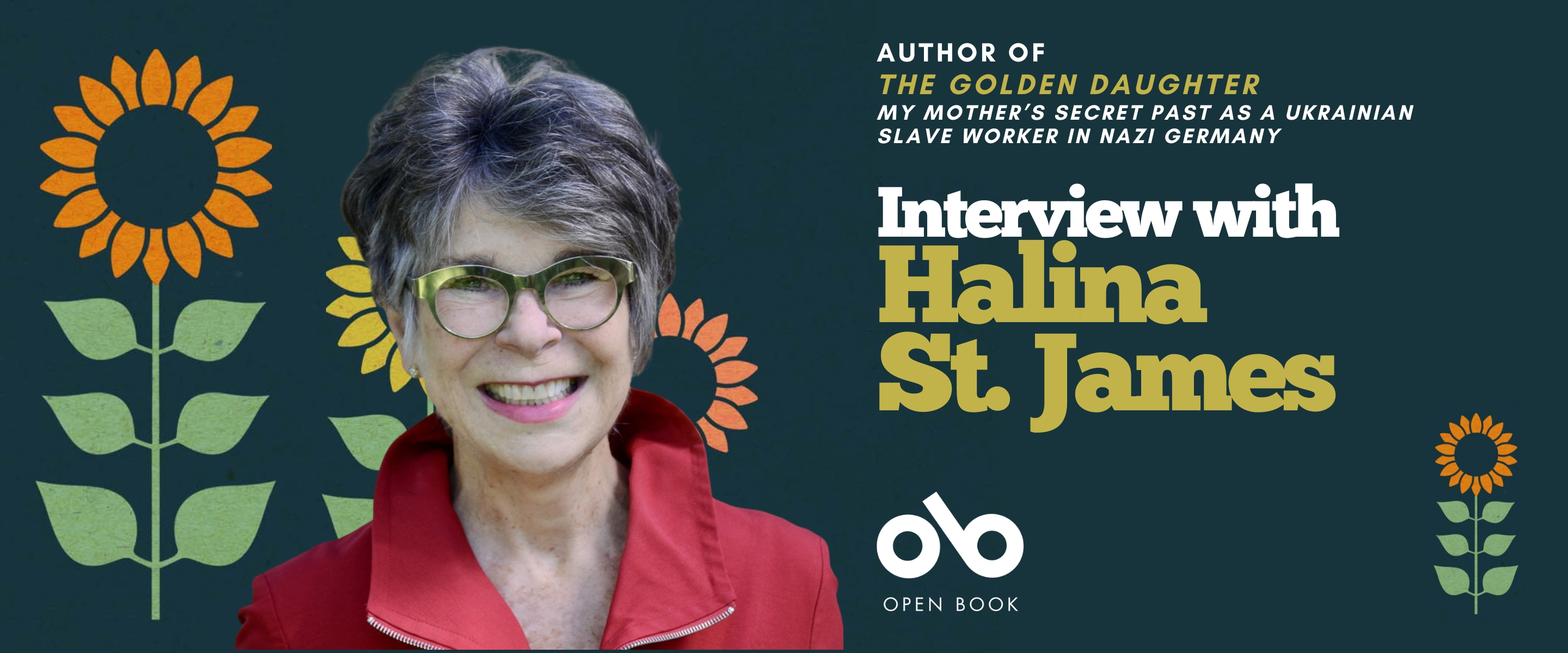

Renowned Journalist Halina St. James Pens a Powerful Memoir in The Golden Daughter

Today, we're featuring a moving and crucial memoir on Open Book, in anticipation of the official release next week. The Golden Daughter is a powerful mother-daughter memoir by Halina St. James that uncovers long-buried family secrets through a trove of wartime letters. When Halina sorts through her late mother Maria’s belongings, she discovers letters revealing a harrowing past: Maria was abducted from Ukraine by Nazis, forced into slave labor in Germany, and later lived in a displaced persons camp where she became pregnant.

Maria’s marriage to a noble Polish man and a later love triangle with his younger friend leads to betrayal and upheaval in postwar Canada. As Halina pieces together this hidden history, she comes to understand the complex legacy of trauma, love, and survival that shaped both her mother’s life and her own. Ultimately, the memoir is a journey of discovery, forgiveness, and reconciliation.

We've got a fascinating My Story Memoir interview with the author to share with our readers, and you can pre-order the book right now from House of Anansi Press!

Open Book:

How did your memoir project first start? Why was this the right time to tell your story?

Halina St. James:

I had no intention of writing a memoir, especially one so heavily dependent on my mother’s story. My relationship with my mother had become more and more strained towards the end of her life.

When she died, I found a bundle of 55 letters, all in Russian or Polish. I didn’t want them. I almost threw them out, but something stopped me. I had them translated. I was stunned at what I discovered.

The letters were mostly from mama’s parents and a few friends. I learned mama had gone to school one day as usual when she at 17 years old in her hometown of Vinnitsa, Ukraine. That fateful day, February 24, 1943, she was snatched from her classroom by the Nazis. She was taken to Germany to work as a slave until the war ended. She never saw her parents, her home, and her country, again. She never told me any of this.

Because of her letters, everything changed. I discovered I really didn’t know my mother at all. I wanted to find more because, ultimately, knowing her secrets, would help me understand who I was.

I went to Germany. I went to the river in Schweinfurt, which “ran with blood’ when mama worked there in the factories producing ball bearing. The factories were bombed constantly. There were no bomb shelters for the workers.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I went to the the grassy field near a suburb in Weiden where the DP (Displaced Persons) camp once stood. Mama was married in Weiden. I was born there. And it was in that camp where mama fell in love with the man who would be my step-father.

When I returned to Canada, I had a very different picture of my mother. She was a survivor. She had to live by her wits and lie to survive. She changed her identity to get out of Germany. The problem was, she couldn’t stop her deceptions after she came to Canada. She never told me the truth. Through her letters, I only discovered a slice of it.

Mama was part of over 5 million slave workers the Nazis stole from their countries, and forced to work in Germany. If they survived the war (and many didn't, because they were worked to death), most, like mama, never spoke about their time in Germany. They were ashamed they were forced to work for the enemy, or they simply wanted to forget.

Now is the time to tell their stories because history is repeating itself. Conflicts, wars, lives lost or destroyed, families ripped apart and democracy itself in jeopardy; today has frightening echoes of World War 2.

OB:

Is there a question that was central to this project? And if so, did you know the question when you started writing or did it emerge from the process?

HSJ:

When I began writing, there was no question central to the story. It was simply the story of my mother’s stolen life, her time as a slave workers in Nazi Germany, how she wound up in a love triangle in Canada, and how she survived being a DP first, in Germany, and then Canada.

But as I wrote, the question emerged. Who was I? I had based my image of myself on someone who deceived me, my mother. She never told me what had happened to her. She never told me about the lies and deception she wove into her life first to survive and to get what she wanted.

As I discovered more about my mother, more about my birth father, whom she never told me about, and more about his family in Poland, the question of my own identity became central to the book.

OB:

If you have written in other genres, what was different for you in writing a memoir?

HSJ:

My other books were ‘how to’ books - how to do something and why. I also wrote a whimsical children’s story for my grandkids called Saving Christmas.

Writing my memoir was an altogether different challenge because I had to delve deep into those secretive places of myself, the places I never talked about. I had to bring up old hurts. Why did my birth father never come looking for me? Why did mama never tell me how much she loved me? Why was I alway the mother, the go-between, the peacemaker to my mother and step father?

I had done therapy for all of this for most of my life. Writing the book was the most challenging therapy of all.

OB:

Did you use any materials, documents, interviews, or other research that became part of the writing process?

HSJ:

My mother’s letters were central to the book but I also filled up four large boxes of research material.

In Germany, I found records of mama as a slave worker, her marriage documents, my baptismal certificate and information about the camps and factories. I found dates and documents in the Arolsen Archives at the International Centre on Nazi Persecution.

Mama kept all her wartime documents. From these, I found my birth certificate, the name of my real father and his camp documents. That led to his unmarked grave in Northern Ontario and meeting the woman who was his care worker in his nursing home in Kirkland Lake. She told me about his last days at the nursing home.

After finding my father, I emailed the municipal offices in Poland where he was born. That email led the discovery of a family I never knew I had. I went to Poland to meet them. There, family members gave me more letters and a Christmas card my father wrote while he was in Canada. And for the first time, a photograph of the father I never really knew.

The man who translated my mother’s letters came from the same area of Ukraine as my mother. He could translate the idiomatic phrases used in her letters and the historical significance of many events. He was able to provide valuable context for that area of Ukraine.

Finally, I read everything I could on the slave workers in Germany.

OB:

Did you experience any anxiety about making a part of yourself public in this way? If so, how did you or do you cope with the vulnerability of publishing a memoir?

HSJ:

I knew before I began writing that this book had to be absolutely truthful and straight from my heart. I knew I would be vulnerable but I felt the story need to to told. I coped with it by crying a lot. I also felt terribly guilty because I really didn’t make my mother’s last years happy.

With every discovery I made, there were more questions. But mama was dead so I had no answers. I blamed myself for not questioning her and for not taking more of an interest in her life when she was alive.

Today, I’m doing therapy for PTSD and Intergenerational Trauma. Often, I still cry about what could have been and then I remind myself, it was not my fault that she did not tell me. And I remind myself, they were her secrets to keep.

OB:

Personal essays, memoirs, and creative nonfiction in general have becoming particularly in demand and loved by readers in recent years. Why do you think creative nonfiction is more popular than ever?

HSJ:

We live in a age where we are drowning in information, much of it meaningless and false. There is no time to fact check everything, even if we wanted to. Everyone wants to sell you something or have you align your opinion with theirs. There seems to be fewer and fewer incentives to live our lives with compassion and kindness.

Memoirs, and creative non-fiction, are everyday stories where real heroes live and wrestle with their lives. They invite us to visit a different world, to see it through different eyes, and to wonder how we would cope in similar circumstances. Memoirs put humanity into history.

_________________________________________

Halina St. James was a journalist for the CBC and CTV, covering revolutions, a war, election campaigns, and three Olympics. Later, she became a performance coach for business and government leaders. Halina lives in Tantallon, Nova Scotia.