Ryad Assani-Razaki Reaches for Hope in The Hand of Iman

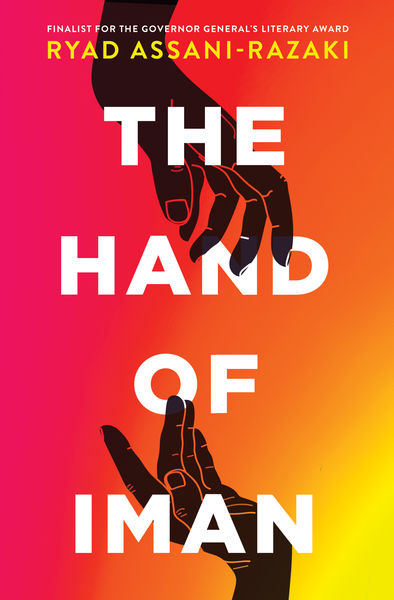

Dreams are a rare commodity in Ryad Assani-Razaki’s debut novel, now available to English-language readers in a striking translation. Set in an unnamed African country where urban sprawl collides with the illusions of Western prosperity, The Hand of Iman (House of Anansi Press) paints a vivid portrait of survival in a place where a child’s life can be bought and sold for a handful of coins. At its centre are two unforgettable figures: Toumani, whose earliest lessons are in the endurance of suffering, and Iman, a biracial boy who dares to believe in escape even as his yearning threatens to consume him.

When Iman reaches out to rescue Toumani, he sets in motion a friendship that offers both solace and danger. Their bond is tested by the harsh realities of exploitation and by the tangled desires that shape their futures, including their love for the same young woman. Assani-Razaki writes with clarity and compassion about resilience in the face of injustice, weaving a story that is both intimate and unflinching.

An award-winning author whose voice has already left its mxark in French-language literature, Assani-Razaki poses a searing question through his work: what is survival without the possibility of hope?

Check out our Storytellers interview with the author, where he shares the origins of this remarkable novel, the choices behind its haunting characters, and why stories of dreaming, however risky, remain vital.

Open Book:

Which authors have inspired you and/or influenced your work?

Ryad Assani-Razaki:

I’ve always used reading as a form of escape. I read what doesn’t relate to me or depicts a world I don’t have access to. I believe good art can make you relate to a foreign situation, by identifying what is common and connects us all as humans. The works that have influenced me the most did just that, connected me with their humanity. There are European works like Annie Ernaux’s on her absent relationship with her dead father, or philosopher Christa Wolf’s extremely personal view on life in Communist Germany. Freedom is to ignore that you are in a cage. Anchee Min or Madeleine Thien’s take on Communist China is vastly different. I enjoyed the Bluest Eye and a lot of Tony Morrisson’s books on being black in America. Jhumpa Lahiri and Arundhati Roy talk about the personal sphere and how it’s impacted by the broader political context. I’ve enjoyed authors that have discussed people and how they must deal with the complex world we have built around us.

OB:

Do you see your writing style or philosophy reflected in a specific literary lineage, or branch of literature?

RAA:

This ties back to the previous question. I write stories that are social or political commentaries. There are two ways to achieve this. The first is what I call “the macro approach” that describes geopolitical conflicts, wars, bank heists in a dramatic fashion, Hollywood-like. I write in the “micro approach”, where deals are being made by politicians or leaders somewhere extremely removed from the stage of the story, and yet somehow this affects a lone boy in a small quiet house. Real drama is silent, it needs no explosion, no gunfire and most importantly presents no antagonist or villain to combat. It is our daily lives. When Louise Erdrich writes “Love Medicine” about the state of Anishinaabe people on a North Dakota reservation, there is no longer any white man to blame. The enemy is despair itself, alcoholism and the loss of hope. These are the dangers we face daily, and to me that is real drama.

OB:

How have you bent or broken the rules of these established literary lineages to develop your own style and voice?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

RAA:

Most of my inspiration is not drawn from literature. I’d call my writing an ode to music, cinema, photography, painting. For instance, there is in my mind a strong parallel between the visual world of the Hand of Iman and that of The City of God, in the brown soil, the shirtless boys with dark sweaty skins. My pacing may come from music, for instance, how does Tupac Shakur paint such an emotional picture of ghettoized urban black America? That’s an inspiration. This is to say, my rules for writing are defined by such an amalgamation of styles that at any point, I’m breaking them. Without revealing too much, the main character in the Hand of Iman is also the only absent one. That’s a rule broken. I’ll end with a loose quote from Toni Morrison who said something like “I wanted to write a story I had never read”.

OB:

What impact would you live your novel or short story collection to leave?

RAA:

As I stated earlier, I’ve generally read books that deal with unfamiliar realities to me. Why is that? To answer both questions, I want to try a fun trip to my meager notions of philosophy, and the concept of the Other. Jean-Paul Sartre says that when someone looks at me, I suddenly experience myself as an object in their world, which creates my value, my freedom, my worth. Simone de Beauvoir illustrates this by saying, you are not born, but rather become a woman, a status imposed by how man define woman as the Other to man who is considered the default. Naturally there is a struggle for dominance. Why does this all matter? The key is when Hegel first introduced the concept. The Other is anyone that is not the Self. To simply be alive is not sufficient to be self-conscious, you need another being to reflect this and recognize you as such. Without the other, you are not. So, it takes understanding that Other, its ways and its values for you to comprehend yourself. You are defined by your specificity and your specificity is defined by what the Other is not. In a world where everybody is white or short, no one is white, and no one is short. I believe we need to respect other’s differences if only because they shape who we are. But to do so, we need to ask the question, who is the Other, and what constitutes him. That’s why I read. If my novel were to do only one thing, I’d like it to bring people to ask the question: who is the other, and why is it important that I respect him?

OB:

Do you think about the place of your work in the broader literary world when you write?

RAA:

Not only do I not, but I believe it’s important for me not to. This goes back to the reason why I write. I write when I face a personal question for which I cannot find a straightforward answer. In the case of the Hand of Iman, the question would have been what could drive an individual to commit a horrendous crime, an unforgivable offence and the worst kind of betrayal. It’s easy to judge, but I’ve learned that often principles are shattered when places are switched. 2pac says: “walk a mile in my shoes and you'd be crazy too, with nothing to lose”. I write to shift perspectives, alienate myself from my convictions and relate to people’s differences. I never intended to publish my first collection of short stories. It was completed and shelved for a year before I was suggested to publish it. I’ve also written full novels that simply disappeared. They were forgotten once I had explored the question they posed and had grown as a person. Having such a personal use of literature, I never really see myself as being in a conversation with other writers or in any specific literary current. I guess for me the point is not to cage myself in any particular corner of the literary world but to ask intimate questions and stay open to honest answers. If someone else finds some gems in my explorations, then so be it.

OB:

What is the next story you’re working on, whatever form it may take?

RAA:

As I mentioned earlier, my reason for writing is to figure out the world and our place within it. One of my interrogations is on the state of Black people in the world. I’ve realized I am on a quest to understand this. My journey started with Deux Cercles, a collection of short stories centered on our differences, with a particular focus on the place and poor treatment of immigrants. It is after all, what I am. The immigrant status represents the end of the journey. In the Hand of Iman, I explored the previous step of that journey, the homeland. What causes us to leave it? The answer is in the history of the interaction between Africa and the West, and how it branded us as immigrants, colonies, and before that, as slaves. My next book logically delves in that history and takes us to the very beginnings of that interaction, before immigration, before colonialism, before slavery, before we were defined by that Other who is the West. What did our first interactions look like, what happened and who were we? The next story I am writing is a historical fiction set in African medieval times and attempts to explore these questions.

______________________________

Ryad Assani-Razaki was born in 1981 in Cotonou in the West African state of Benin. In 2009, his short story collection Deux cercles was awarded the Trillium Book Award. His debut novel La main d'Iman won the Prix Robert-Cliche in 2011 and was shortlisted for the Governor General's Award for French-language fiction in 2012.