Saad T. Farooqi Grasps a Sliver of Hope in the Unique Dystopian Landscape of White World

Inspired by lived experiences, and the geopolitical issues that have gripped the countries that he's lived in, Saad T. Farooqi has always had a desire to write dystopian stories that speak to the heart of the human condition, and the world around us.

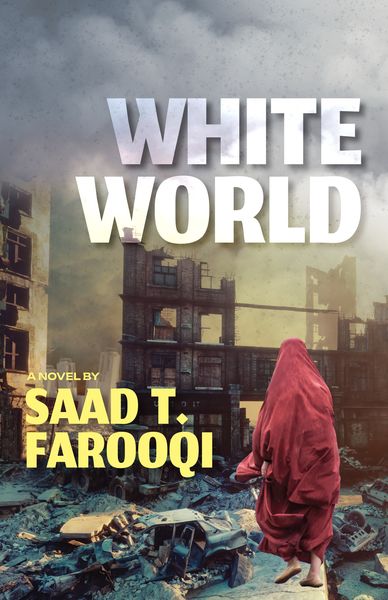

In his new novel, White World (Cormorant Books), the author transports readers to late 21st century Pakistan, reaching beyond established narratives to create a unique speculative work that truly explores the most fraught and damaging aspects of the political climate in the country, eschewing more romantic ideas that have unpinned much of previous literature about this specific place.

His pathway into this world is Avaan, a gunslinging apostate pariah living under the weight of martial law and religious bigotry. He has lost everything to this place, and finds himself torn between political, military, and criminal forces that either want him dead or to join their cause. But, in the middle of all of this chaos, he grasps a sliver of hope that his beloved Doua is still alive. What follows is Avaan's last stand against these warring entities, in one final effort to find the woman he loves.

Check out this riveting Long Story Novelist interview with the author, where he speaks about the origins of this novel and the experiences that made him a writer.

Open Book:

Do you remember how your first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Saad T. Farooqi:

One of my earliest short stories was about a man wandering a barren city in a state of delirium. There is no color. Not in the sky, not in the ground, not anywhere. He keeps ambling through this colorless wasteland until he reaches the horizon where he finds a woman levitating in the sky, draped in a red garment that extends to the clouds. I was sixteen when I wrote that, and it’s probably still somewhere in a forgotten cardboard box along with other stories I wrote as a teenager. Those who’ve read White World will recognize this since a similar scene appears in the novel. Likewise, lost love, internal and external religious turmoil, and isolation in a muted dystopian city were always there in anything I wrote. If anything, White World is the distillation of some of the stories I’ve written since I was fifteen, given a more coherent narrative structure.

OB:

How did you choose the setting of your novel? What connection, if any, did you have to the setting when you began writing?

STF:

For as long as I can remember, I’ve written dystopian stories of a man’s quest to reunite with a loved one. Dystopian because I’ve never felt like I truly belonged to any country or creed. Maybe it’s to do with the fact that I moved around a lot since I was a child or often went through periods of intense isolation (bullying, ostracization, etc.). For better or worse, the only story I could then tell was one where everyone was as deracinated from a collective identity as I was. The earliest short stories I wrote involved phantom-like cities with no distinct cultural or geographical markers. These cities were oppressive and alienating, in some ways more sinister than any villain. I’ve gravitated towards the film noir aesthetic for this very reason because once again, you’d have the protagonist battling rain, hail, or snow as an external metaphor for their inner strife. The first thing I wrote down when jotting down notes for White World was describing the snow as ephemeral and toxic, something beautiful at a glance but deadly up close.

Originally, White World was supposed to take place in a fictional Asian country with various ethnicities and religions. Avaan, however, was always Pakistani and over time, I decided to set the whole story in Pakistan. For one, there has never been post-apocalyptic fiction set in Pakistan. More importantly, it allowed me to explore my disillusionment and dismay over what my country has become. There’s a reason I’ve scarcely visited Pakistan in thirty years.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

STF:

The earlier drafts were much more pessimistic, philosophically and thematically. In the original ending, all major characters were dead by the final chapter. While the narrative is still dark, I’ve since moved away from such a somber ending simply because I don’t think despair is the final solution to the human condition. It’s merely the first step in finding a personally satisfying reason to keep living. That said, I believe all happy endings must be earned by the characters.

OB:

Did you find yourself having a "favourite" amongst your characters? If so, who was it and why?

STF:

Writing from Avaan’s point of view was a real pleasure. I find him to be sensitive, selfish, and sardonic but also a true romantic at heart because he will go through a meatgrinder for those he loves. That said, discovering Red’s voice and then writing in it was the hardest thing I’ve ever done as a writer. Seeing people resonate with her and say she’s their favorite character in the book has been a great source of pride for me.

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

STF:

There is a part in the novel where a character loses their eye. To fully immerse in the POV, I spent a few hours every day with a bandage over my eye to get a feel of light and depth perception. Everyday tasks proved to be quite the challenge. That said, cooking was the real surprise—I did not expect it to be that hard with just one eye!

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

STF:

Paul Auster.

The Book of Illusions is one of my all-time favorite novels. My philosophy professor first recommended it to help hone my writing. Some twenty years later, it’s still a novel I read whenever I need inspiration. In the fifteen years it took to write White World, there were brief moments when I wondered why I was still writing. In moments like this, I would turn to The Book of Illusions because of the richness of its narrative, the harmony of its prose, and the complexity of its themes. Especially that of the storyteller and their often destructive relationship to their story. I owe so much of my creativity and imagination to Paul’s writing and when we lost him earlier this year, it was a foregone conclusion that I would dedicate White World to him.

OB:

What if, anything, did you learn from writing this novel?

STF:

In the fifteen years I’ve spent writing and re-writing White World, so much of what I describe in the novel politically and socially has come to pass in Pakistan. The infamous blasphemy law continues to be used as a cudgel against non-Muslims, often as vigilante “justice” with tacit consent from a sizable portion of the public. In 2021, a bill was passed that made anyone critical of the army face up to two years in prison or be fined C$2400. Or both. And while I was delighted to see Pakistan recognize transgender individuals as rightful citizens under Transgender Persons Act 2018, these rights are tenuous at best. True to it, less than five years later, this act was labeled incompatible with Islamic principles by the Federal Shariat Court. Pakistan still ranks as one of thirteen countries where atheism and apostasy are legally punishable by death.

So, what did I learn while writing this novel? I’ve learned, again and again, that reality can be more stiflingly ugly than anything I can conjure in my mind.

____________________________________________

Born in Saudi Arabia, Saad T. Farooqi moved to Pakistan before his first birthday. There, he survived three separate kidnapping attempts before he was eight. His family eventually settled in the United Arab Emirates. After initially enrolling in electrical engineering to please his parents, Saad graduated with a BA in English Literature from the American University of Sharjah. He then earned an MFA in Creative Writing from Kingston University, London. Saad immigrated to Canada in 2015 and resides in London, Ontario. At Kingston University, he studied under several notable authors, including Rachel Cusk and Elif Safak. His short stories and poems have appeared in various magazines in the US, UK, and UAE.