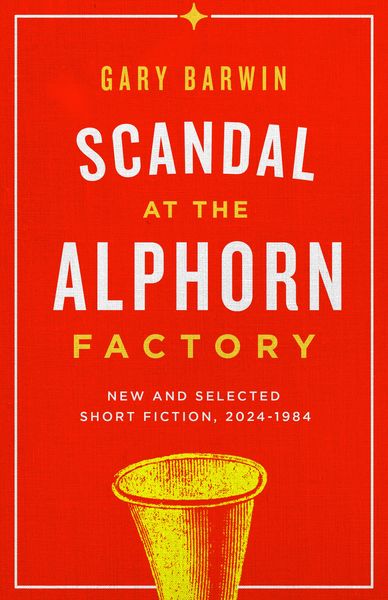

Scandal at the Alphorn Factory Brings 40 Years of Magical Gary Barwin Stories Together in a Definitive Collection

Author to over 30 titles in total, Gary Barwin is a mainstay on the CanLit scene and a renowned short story writer. It will come as no surprise to readers of his work that his catalogue includes a considerable number of fiction collections, released throughout his career.

The new and exciting publishing house, Assembly Press, has brought Barwin into the fold to share Scandal at the Alphorn Factory: New and Selected Short Fiction, 2024–1984, made up of the best of his stories. The author is known as a gifted humourist and teller of magical, fantastical tales that fully immerse readers in dream-like worlds and explorations of the human condition, and those skills are on full display in this tome of magnificent collected works.

We're delighted to share this Keep It Short interview with Gary Barwin right here on Open Book, where he discusses short story writing and his journey to this new collection.

Open Book:

How did you decide what stories to include in the collection? When were they written?

Gary Barwin:

I don’t know what is a story, what is a short story, what is a prose poem, what is a poem, what is prose, what’s a script, what’s an essay, and what is a luminous inscription on the dark platen of the universe, written with cloud, confession, lemur breath, sorrow, hadrons, and a three-act structure with a meet cute. So, I included all of those in the book. The idea of my book is to explore a range of what is possible in short fiction—at least, what I’ve explored. I’m really happy with the range, and really proud of the work of that 40-years-ago whippersnapper young Barwin, at least the work that I included.

Scandal is a new and selected, so the trickiest part was what to include from 40 years of published writing (from when I was 20 to my current wizened hoarybeard carbon-dating of 60.) My friend, the writer and scholar Alessandro Porco made some initial suggestions (he was the editor for my selected poems and had read everything I’d ever written including my laundry lists—how long has it been since people wrote laundry lists?) and then I took it from there. It’s hard to leave some pieces out in the cold, but we couldn’t include everything. I was really happy to find a “forever home” for some stories that never got the attention I wished they had and/or whose presses are now gone—I still grieve your loss, The Mercury Press!—and especially, to mix together an entire goulash across time, style, and approach. Leigh Nash, the editor of Assembly Press, and I decided to order the entire collection backwards which is why the subtitle is “New and Selected 2024-1984.” The new and unpublished work is first, then the sections go from most recent to oldest. It feels thrillingly like time travel, traveling back to the roots, sources and invention of things, or at least, to my origins there.

OB:

What do the stories have in common? Do you see a link between them, either structurally or thematically?

GB:

It’s a really germane question: Do you remain the same person or do you become someone different over 40 years? What’s changed, what’s stayed the same? And as a writer, I’m intrigued by what approaches, concerns or techniques that are shared over the years and how they’ve developed in sophistication and nuance. Or not. I’ve also an affection for the youthful energy of some of the work. I think I’m happy that most of the pieces are recognizable as the work of the same writer. It’s not that I’ve only a handful of ideas, but rather I’ve got perennial concerns and influences. I’m interested in style and tone. How using language is like holding dowsing sticks: if you pay attention, it leads you places, both inside you and in the world of emotion and story. Sometimes it seduces you with its glib assurances, sometimes it wakes you up. I hope all the stories are centred in alert and insightful compassion. For people. For writers, readers, users of language. For language itself.

OB:

How did you decide which story would be the title story of your collection? Why that story in particular?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

GB:

There isn’t a story with the exact title, but there is “A History of the Village” where the narrator is reading a book that refers to an alphorn factory. As I say in the introduction to my book, “I’m attracted to images that, like the alphorn, are both simple real-world objects and yet also uncanny and magical. Alphorns are very basic wooden horns, but at the same time, they’re twelve feet long and used to signal from Swiss mountaintops. To me, the alphorn reveals the wonder and strangeness of the world and the human imagination. Their doleful high-altitude bleating speaks to tenderness and uncertainty, and to the bewildering and marvellous situation of being alive.” That’s what I want the book as a whole to do while also being involved in the trickster nature of language itself.

OB:

What do you enjoy most about writing short fiction? What is the toughest part?

GB:

When I begin at the top left of the screen, I don’t know what is going unfold. I don’t know if I’m in for a long complicated trip or a short anecdote. Sometimes, I have a sense of scale, a kind of understanding of the texture of the unfolding, but I’m often surprised. I try to remain open and let the work suggest things to me. I love this sense of the unknown and unexpected. It’s deep spelunking into the imagination. I love how I feel centred, charged up by the process of exploration and discovery. How it feels like learning and possibility. I’m one of those writers who loves to write.

Part of trusting this process, is also understanding that it doesn’t always yield anything interesting. So, this is the tough part. Self-doubt and worry. Even if I wrote something I think is good yesterday, I feel badly if I can’t today. Or if I look back at that thing that I wrote yesterday that I thought was amazing, and it turns out, it wasn’t, but rather it was more about the thrill of making it, or that I was just trying too hard. And then sometimes—and this is common with lots of writers, I think—if others don’t like the work, I’m disappointed. Ultimately, the mature writer part of me is fine with that, the deep source of my interest in writing isn’t about that, but there’s always the petulant adolescent writer-person lurking in the shadows feeling unloved. Of course, this isn’t about short fiction per se, it applies to all my writing, and well, everything.

Something I love about short fiction but that is also challenging is knowing if it’s over. I suppose that applies to relationships, too. The brilliantly oblique ending line or scene. Whether to end with a cymbal crash or to suddenly cut away right at a key moment. With a bang or whimper, image or generalization. How much is too little, how little is not enough? And then the owl sat on sad three-legged stool and remembered what was difficult about calculus and losing its mother.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

GB:

There’s a story (“Cares of a Family Man”) where (spoiler alert!) a husband and wife discover Hitler’s moustache hiding in the attic like a mouse. I wrote about them finding it, putting it in a box like a little lost nestling, then learning what it was. They nurture it as you would a fallen bird. I mean, it’s just the moustache, it’s not the man. I didn’t know where the story was going: what was going to happen? What’s the implication of finding this little thing? But then as I got to what turned out to be the end of the story, something happened. I won’t say what it is (non-spoiler alert!) but I literally shuddered as I wrote it. And also laughed. This, to me, is the best kind of writing experience. You’re so immersed in the world of the story, your writer antennae receiving transmissions from all over your brain—your memory, thoughts, sense of history and the culture—and, if you’re lucky enough not to get in the way of the process, something emerges from the words in front of you that you didn’t expect, didn’t exercise choice about exactly, at least not initially. I think it’s about channelling a larger sense of story—sense of the world—than the rational mind. You’re able to synthesize more than you are consciously aware of. And then this comes out in the writing.

OB:

Do you have a favourite short story collection that you've read? Tell us why it is special to you.

GB:

Franz Kafka’s short fiction has always been my earnest ironic uncanny lodestar illuminating the absurd and anxious marvel that it is to be alive. I’ve been reading Kafka since middle school. Oh, the troubled weltschmerz of those existential trudges to the school bus stop, carrying that lunch of baloney and Dunkaroos in my backpack as if it were the paradox of mortality and suffering itself.

This just in: In terms of more recent fiction, I’m in the middle of reading Spencer Gordon’s new book, A Horse at the Window which I just bought yesterday. Is it short fiction? Prose poetry? I think so. So far, it's brilliant.

___________________________________________

Gary Barwin is a writer, composer, and multidisciplinary artist. He is the author of 31 books including Imagining Imagining: Essays on Language, Identity and Infinity and Nothing the Same, Everything Haunted: The Ballad of Motl the Cowboy which won the Canadian Jewish Literary Award, was shortlisted for the Vine Award, and was chosen for Hamilton Reads 2023. His national bestselling novel Yiddish for Pirates won the Leacock Medal for Humour and the Canadian Jewish Literary Award, was a finalist for the Governor General’s Award for Fiction and the Scotiabank Giller Prize and was long listed for Canada Reads. His 2022 poetry collection, The Most Charming Creatures won the Canadian Jewish Literary Award. A PhD in music composition, he has been writer-in-residence and taught at many universities, colleges and libraries. He lives in Hamilton and at garybarwin.com.