"She Saved Our Lives, But it Cost Her a Great Deal" March Writer-in-Residence Amanda West Lewis on the Story Behind Her New YA Novel

It's a daunting task to take on capturing New York City in the 60s, but Amanda West Lewis is more than up to the job in her tough, compelling, autobiographically inspired young adult novel These Are Not the Words (Groundwood Books).

Missy's life in New York seems enviably cool from the outside: her loving, talented mother has gone back to school to study art and follow her dream, while her charming father sneaks Missy to jazz clubs in Harlem and the Village to catch history-making acts.

But as Missy's father's struggles with alcohol and drugs slowly begin to eclipse the good times, both Missy and her mother end up with impossible choices to make. A story of hope and love, loss and change, These Are Not the Words is a family story of deep truth set against the background of one of modern history's most vibrant backdrops, expertly rendered by West Lewis.

Today, we're excited to announce that Amanda will be joining Open Book as our March 2022 writer in residence. You can get to know her and her new book today in our interview below, and be sure to stay tuned to the writer in residence page throughout the month to read new, original content from a writer with a searingly keen eye and memorable, vibrant voice.

Today Amanda tells us about the iconic New York setting that was so much fun to research it was tempting to set her whole book there, how one major editorial change unlocked the entire book's true voice, and the tough, essential lesson from her mother than inspired the book's beautiful dedication.

Open Book:

Do you remember how you first started this novel or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Amanda West Lewis:

Yes, vividly. I was in the Picture Book Intensive at Vermont College of Fine Arts. We did a lot of writing prompts from physical memories of early childhood and, inevitably, all sorts of things bubbled up. I had a strong sense memory of the apartment I lived in as a child. I remembered walking through the living room late at night, when I was about five years old, tiptoeing through “adultland.” The sounds and smells were almost overpowering. I drafted a picture book about that moment and some of the moments that followed. Because it was a picture book, I pared down the language to leave room for imagination and illustration. I was writing a lot of poetry at the time, and I wanted the images that I was creating to be evocative, rather than to be telling a story.

I knew that what I wrote in that workshop wouldn’t actually work as a picture book, but there was a core that I thought would resonate with an older reader. The novel has that kernel, that exposed edge of seeing my life through my child-eyes. In fact, in order to answer this question, I re-read the picture book manuscript and was delighted to find same voice. The genesis of the novel was in the act of writing those memory prompts.

OB:

Did the ending of your novel change at all through your drafts? If so, how?

AWL:

I had written an ending that tidied up all the dangling bits. It was very satisfying, but too pat. Too clean. In constructing a tidy ending, the novel felt false. I think the reader would have come away with a sense of hopelessness. Thankfully, my editor Shelley Tanaka wouldn’t let me get away with it. Both she and publisher Karen Li said that life is messy and maybe I didn’t need to supply answers. So, I re-wrote it to allow the ending to be much more open and unresolved. As a result, the feelings at the end of the novel are far truer to the autobiographical essence of the story. You know that Missy’s going to have to keep working at this, but she now has the tools to do so.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Did you do any specific research for this novel? Tell us a bit about that process.

AWL:

My memories of New York City are the memories of a child, and my character is older than I was when I lived there. I needed to do extensive primary research –– talking to people who were there in 1963 –– and then to fact check to make sure their memories were accurate. Admittedly, I love research, so diving into New York City in 1963 was a real treat.

I also had to research the music of the period. I grew up with jazz, but not as a musician. I had great conversations with drummer Jeff Asselin, who helped me to listen with the ears of a drummer and find words to transpose sounds on to the page.

One of my biggest research rabbit holes was The Chelsea Hotel. The detail of the father staying at the Chelsea is based on historical fact, but there was no one personally I knew who was there at that time. I was lucky because Inside the Dream Palace: The Life and Times of New York’s Legendary Chelsea Hotel by Sherill Tippins had just been published. It gave me all the background I needed, and more. It was all I could do not to set the whole book there!

But perhaps the biggest part of my research came from photographs. My father was a photographer and I have many good prints from the 1960s. Along the way, I discovered several photographs that I took of myself at that time. I would have been only five years old, but my father had taught me to use a timer. So, I had photographs of me in the settings that I write about. I analyzed them forensically to put myself in that world.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

AWL:

The novel was originally written in third person. The feedback I received was that it had a detached, slightly nostalgic tone that wouldn’t work for a young person. In a moment of frustration, I decided to re-write one of the chapters in first person, just as a writing exercise more than anything else. I vividly remember getting goosebumps when I made that change. The story suddenly came alive. It felt so very, very right. I realized that even though the novel was autobiographically based, I had been avoiding putting myself inside the story. I had been standing outside and looking in at it. Now, suddenly, the smells, tastes, colours, and sounds vibrated. I breathlessly messaged my writing group and with them cheering me on, I re-wrote the whole novel in first person. Then I cried for about two days solid.

OB:

Who did you dedicate your novel to, and why?

AWL:

The book is dedicated to my mother. I owe her everything. She saved our lives, but it cost her a great deal. She loved a man who was terribly self-destructive and damaging. Loved him fiercely, so fiercely that she could have easily lost herself in his chaos. But she chose me and loved and protected me.

Ultimately, my mother showed me how important it is to choose. She taught me that there is always a choice and by being aware of my choices, I would feel in control of my life. Even if the choosing is painful, even if it might not even be the right choice, I could choose. If I didn’t think there was a choice, I should look at my behaviour. Because when I did that, I could probably see that I’d already made a choice. I could accept that choice or change it.

OB:

Did you include an epigraph in your book? If so, how did you choose it and how does it relate to the narrative?

AWL:

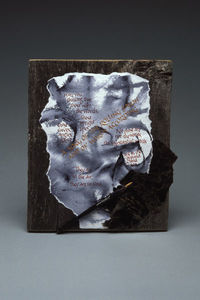

As well as being a writer, I am a professional calligrapher. A couple of years before I wrote this book, I did a series of art pieces using excerpts from Leaves of Grass by Walt Whitman. One of my favourite poems from that collection is "Song of the Rolling Earth". It’s a poem that explores the physical nature of language –– the way that words look on the page and the way that they sound coming out of your body. It’s a poem that reminds me to go beyond the surface of writing and back into the meaning of the words. When you are a calligrapher, you are in love with the shapes of letters on the page. But as beautiful as they are, the shapes are only pale reflections of your desire to connect with a fellow human being. Missy and Pops write poetry to each other to try to share their deepest selves. They use words, but the words in themselves are not enough to carry their love for each other.

Were you thinking that those were the words, those upright lines?

those curves, angles, dots?

No, those are not the words, the substantial words are in the

ground and sea,

They are in the air, they are in you.

_________________________________________

Amanda West Lewis is the author of seven books for young readers, including September 17, which was nominated for the Silver Birch Award, the Red Cedar Award and the Violet Downey IODE Award. Her new novel, These Are Not the Words, is available from Groundwood Books. She is a writer, theatre director, calligrapher, and drama teacher. She is the founder of the Ottawa Children’s Theatre, and she has an MFA from Vermont College of Fine Arts. Born in New York City, she now lives in Brooke Valley, Ontario, with her husband, writer Tim Wynne-Jones.