"Tender and Smart, Sometimes Savage Poetry" A Conversation with the 2023 Griffin Poetry Prize Finalists

This week, on June 7, poetry lovers and publishers will be gathered, waiting to hear one of the biggest announcements of their year: that evening, the winner of the $130,000 Griffin Poetry Prize will be revealed at an event in Toronto.

The prize, which is the world’s largest international prize for a single book of poetry written in, or translated into English, recently merged their two former awards (one for Canadian poetry books and one for books from other countries) into a single entity. 2023 marks the first year the prize will be given as a single and, by literary award standards, massive award.

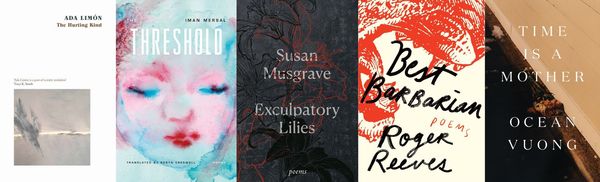

The nominees are a highly decorated bunch already. They are Iman Mersal, nominated for her collection The Threshold, and Robyn Creswell, who translated Mersal's book into English; Ada Limón, author of The Hurting Kind; Susan Musgrave, author of Exculpatory Lilies; Roger Reeves, nominated for Best Barbarian; and Ocean Vuong, nominated for his collection Time Is a Mother. Amongst them they count honours including the Guggenheim Fellowship, the MacArthur "Genius Grant", and the Whiting Award, to name just a few.

We're excited to speak with the 2023 finalists for the prize, with the exception of Vuong, who was unavailable for interview at press time.

From the finalists, we hear about the behind the scenes of life as one of the world's most celebrated poets, from working through as many as 50 drafts for each poem, navigating the author-translator relationship, the effects of parenthood and grief on the writing process, and more. The nominees also share beloved reads from their respective countries, making for a spectacular recommendations list for anyone looking for reading inspiration.

Tickets are available for the June 7 prize announcement event, which will include readings from all the finalists and the Canadian First Book Prize winner, Emily Riddle.

Open Book:

Tell us about your nominated collection and how the project originated for you.

Robyn Creswell:

When I became poetry editor of The Paris Review in 2010, I had a list of poets I hoped to publish in the magazine and Iman was at the top of that list. I was a graduate student at the time, studying modern Arabic literature, and Iman’s work was unlike anything else I’d been reading: she took everyday life as her subject—its tones, intimacies, embarrassments, illuminations—and turned it into poetry. Tender and smart, sometimes savage poetry. Iman sent me a few poems and I translated one of them, called "Celebration". We published a few more during my time at the Review and kept working—very slowly but steadily—on others, until we had no choice but to do a book.

Ada Limón:

The Hurting Kind is my sixth book of poems and, for me, it's the book that is most interested in exploring interconnectedness. I wanted to write a book that was about honouring our earth, the planet, the human ancestors, and the plant ancestors, and the animals. This book is very intimate, but it also reaches outward. The first few poems of the book explored what it was to be in a reciprocal relationship with the land around me, and as the book grew, each poem seemed to be interested in not only a connection, but a sense of wholeness.

Iman Mersal:

In 2010, when Robyn Creswell became poetry editor of The Paris Review, he sent me an email asking if I would share some poems with him. I did. His translation of one of those poems, entitled "A Celebration", appeared in The Paris Review shortly afterward. He continued translating other poems that appeared in The Nation, and The New York Review of Books, among others. The idea of a book came later; I think it was suggested to us by readers and editors who asked for more. The Threshold is a selection from four poetry books, the first of them published in 1995. It includes at least two different sensibilities, two different moments in my life, and in modern Arabic poetry. We worked closely together on the translations for years. However, I preferred not to choose the poems. I believe the choice should come from the translator’s desire to carry particular poems to his own language. Robyn was already quite familiar with my later poetry; he had to work harder to capture the anger, frustration, playfulness, and humour in the earlier poems. How Robyn worked through these poems was inspiring for me.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

We talked a lot about the order of poems in the book. This was the fun part. We discussed how the poems would sound in English, and how we could maintain a continuity of voice. But we also wanted there to be a contrast, or a silence, between successive poems.

Susan Musgrave:

I started writing the poems in Exculpatory Lilies, in 2010. I don’t set out to write books of poems; poems just find their way into my life, if I’m lucky. And receptive. I write slowly; the average poem goes through 30-50 drafts. This collection revolves around the life and death of my husband, Stephen Reid, in 2018, and our daughter, Sophie, in 2021.

Roger Reeves:

My collection is about many things—grief, fatherhood, jazz, ecstasy, the ancientness of subjectivity, of our "I" in poems. The project originated out of a confrontation with the loquaciousness of our times, out of the death of my father, out of the birth of my daughter. The project announced itself with the poem "Children Listen". It was in that poem that I said something via poetic form and lyric meditation that announced a new direction, a new place to go and hunker down in.

Open Book:

Are there images, themes, or questions you notice recurring in your work? If so, what are they?

RC:

As a translator, the images and themes aren’t up to me, but we titled Iman’s collection The Threshold because there are lots of thresholds (‘atabat) in her work—boundaries that get crossed, episodes of transgression and transformation. The German critic Walter Benjamin writes somewhere, “We have grown very poor in threshold experiences,” but in Iman’s poetry the ‘ataba regains its old power of enchantment.

AL:

The threads that run through my book The Hurting Kind are the observation of the natural world, a recognition of our own mortality, and the honouring of ancestors. The question I am almost always asking, "How do we live?" I am interested in how desire works in tandem with grief.

IM:

Revisiting one’s work and rereading it carefully—as I’ve done while Robyn and I worked on The Threshold—can be surprising. I always supposed that my writing was concerned with memory’s neglected or excluded moments. While reading my poems again and again, I realized that geography is my way of navigating personal memory, as if geography and not just history were my vessel of memory. I also realized that although I’ve always thought the individual was at the center of my work, the poems don’t avoid questions of collectivity. The self of my poems is constantly reaching out, sometimes in ways I hadn’t noticed, and in dialogue with the world around it.

SM:

Grief. Yearning. Sorrow. Suffering. Marriage. Sex. Rain. Wind. Tenderness. Humility. Kingfishers (I live on a river where I can watch them, day after day.) Loneliness.

RR:

I return to the elegiac in the form of my father’s death throughout the collection. However, the collection also meditates upon the birth of my daughter and becoming a parent as my father is dying. I felt as if I were a door—somewhere between my daughter and my father. I was something that had to be passed through. I was somewhere between birth and death. I was liminal. That liminality made me feel keenly the unstated and invisible last line of every poem—"but you’re going to die." And so I returned over and over again to the grief of death and the ecstasy of living.

Open Book:

Tell us what a typical writing day (if such a thing exists for you) looks like while you’re working on a collection.

RC:

It looks extremely boring! If I’m translating, the only things I really need are a desk—mine is the kitchen table—a cup of tea, and my dictionaries. I drop the kids off at school, then hunt and peck away.

AL:

I write a little bit every day. There's something about writing myself into the world that allows me to feel alive. To feel connected. At times, I don't get to the page, or it's just a small note, but every time I write something, anything, I am reminded that I am a human being in wonder. I travel a great deal, but even on planes and in hotel rooms I find moments to write.

IM:

I don’t think there is a typical writing day. A writer is at work as long as he is alive, inspired by his surroundings and walking toward something, even if the destination is not clear. In my youth I was a night person; I would read and write while others were asleep. For years after becoming a mother, I used to work whenever I found time, sometimes while feeding or bathing my kids. Now, I am more of an early morning person; I try to find two hours of solitude before talking to anyone. When I get to the editing process, I prefer to be completely devoted to it, undistracted by any other task.

SM:

No two days the same. I wait until a line, an image, comes into my head, and jot it down, wherever I am. The rhythm of walking will sometimes bring lines of poems into my head and I try to remember these lines so I can write them down when I get home. If something is worth writing, I tell myself, it should be memorable.

RR:

A typical writing day begins with plunging into reading and writing immediately, which means it actually began the evening and night before. The evening before I’m reading writers that I’m looking to be in conversation with the next morning in the work. Or writers whose work comes to mind as I’m beginning to imagine the language of the poem. Then, the evening before, I’m doodling of sorts, casting about the language in my head for a potential line to start the next morning. When I wake, I wade in.

Open Book:

This is the first year the Griffin Poetry Prizes have merged into a single prize open to writers from any country. If you could recommend one poem or collection that you feel is a great representation of your country’s poetry culture, what would it be?

RC:

I wouldn’t want to burden any single book with the responsibility of national representation. One recent book of poems I’ve especially liked reading is Srikanth Reddy’s The Underworld. It’s wise and humane and deeply funny. If I’m allowed to recommend an Egyptian book, it would be The Collected Poems of Osama al-Danasouri. Most of al-Danasouri’s poems haven’t been translated into English, but they should be.

AL:

One of my all-time favorite collections is Natalie Diaz's book Postcolonial Love Poem. It's a triumph.

IM:

I would recommend so many poems in Arabic, classical, and contemporary. But my recommendations are not a representation of my country or culture but of my sensibility. Here is “Butterfly Dream”, a short poem by the Iraqi poet Sargon Boulus (1944-2007). It is not his best poem, but it came to my mind recently for no particular reason. I think this is what a good poem does. It comes to mind for no reason.

Butterfly Dream

The butterfly

that fluttered as if tied

with an invisible threat

to paradise, almost

brushed my chin

as I sat on my favorite

bench in the garden,

shaking last night’s

nightmares

from my head.

Tr. by Sargon Boulus

Knife Sharpener, 2010

SM:

An anthology is a good place to start. A sampler. You get a bite, a taste, of many different poets, styles of poetry. I’d recommend 70 Canadian Poets, edited by Gary Geddes, published by Oxford University Press.

RR:

There’s not one poem or collection that could represent a country. Singularity is the antithesis of nation—or, at least, should be. Here are a few collections and poets that I believe illustrate the abundance of America’s poetry culture—Dien Cau Dau by Yusef Komunyakaa, The Black Unicorn by Audre Lorde, LOOK by Solmaz Sharif, Elegy by Larry Levis, Song by Brigit Pegeen Kelly, Bewilderment by David Ferry, Of Being Numerous, George Oppen, Trilogy by H.D., BLACKS by Gwendolyn Brooks, Wind in a Box by Terrance Hayes, Duende by Tracy K. Smith, Thrall by Natasha Trethewey, The Rest of Love by Carl Phillips, Postcolonial Love Poems by Natalie Diaz, The Tradition by Jericho Brown, Imperial Liquor by Ahmaud Johnson, Eye Level by Jenny Xie.

___________________________________________________

Robyn Creswell teaches comparative literature at Yale University and is a consulting editor for poetry at Farrar, Straus and Giroux. He is the author of City of Beginnings: Poetic Modernism in Beirut and contributes regularly to The New York Review of Books.

Ada Limón is the author of six books of poetry, including The Carrying, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award and was named a finalist for the PEN/Jean Stein Book Award. Her book Bright Dead Things was nominated for the National Book Award, the National Book Critics Circle Award, and the Kingsley Tufts Poetry Award. Her work has been supported most recently by a Guggenheim Fellowship. She is the new host of American Public Media’s weekday poetry podcast, The Slowdown. She grew up in Sonoma, California and now lives in Lexington, Kentucky where she writes and teaches remotely. She is the 24th Poet Laureate of the United States.

Iman Mersal is the author of five books of poems and a collection of essays, How to Mend: Motherhood and Its Ghosts. In English translation, her poems have appeared in The Paris Review, The New York Review of Books, The Nation, and other publications. Her most recent prose work, Traces of Enayat, received the Sheikh Zayed Book Award for Literature in 2021. She is a professor of Arabic language and literature at the University of Alberta, Canada.

Susan Musgrave lives off Canada’s West Coast, on Haida Gwaii, where she owns and manages Copper Beech House. She teaches in University of British Columbia’s Optional Residency School of Creative Writing. She has published more than thirty books and been nominated or received awards in six categories⎯poetry, novels, nonfiction, food writing, editing, and books for children. The high point of her literary career was finding her name in the index of Montreal’s Irish Mafia.

Roger Reeves is the author of King Me and the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, a Ruth Lilly and Dorothy Sargent Rosenberg Fellowship from the Poetry Foundation, and a 2015 Whiting Award, among other honours. His work has appeared in Poetry, The New Yorker, The Paris Review, and elsewhere. He lives in Austin, Texas.

Ocean Vuong is the author of the critically acclaimed poetry collection Night Sky with Exit Wounds and The New York Times bestselling novel On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous. A recipient of the 2019 MacArthur “Genius Grant,” he is also the winner of the Whiting Award and the T. S. Eliot Prize. His writings have been featured in The Atlantic, Harper’s Magazine, The Nation, The New Republic, The New Yorker, and The New York Times. Born in Saigon, Vietnam, he currently lives in Northampton, Massachusetts.

![black banner image with the griffin poetry prize logo at the top and open book logo at the bottom. Text in between reads "[there is an] understated and invisible last line of every poem" and "a conversation with the Griffin Poetry Prize finalists" black banner image with the griffin poetry prize logo at the top and open book logo at the bottom. Text in between reads "[there is an] understated and invisible last line of every poem" and "a conversation with the Griffin Poetry Prize finalists"](/var/site/storage/images/media/images/open_book_griffin_interview_banner/117175-1-eng-CA/Open_Book_Griffin_interview_banner.jpg)