The 2021 Atwood Gibson Writers' Trust Fiction Prize Finalists Each Share Their Favourite Part of the Writing Process

It's book prize season in Canada and for fiction lovers, one of the most exciting prizes has just gotten a fresh reboot. The Atwood Gibson Writers' Trust Fiction Prize has gotten a new lease on its venerable life this year with a new name honouring (of course) writers Margaret Atwood and her late partner Graeme Gibson, and an enriched prize purse courtesy of philanthropist Jim Balsillie. With a whopping $60,000 for the winner, it's a lot on the line for an exciting list of finalists.

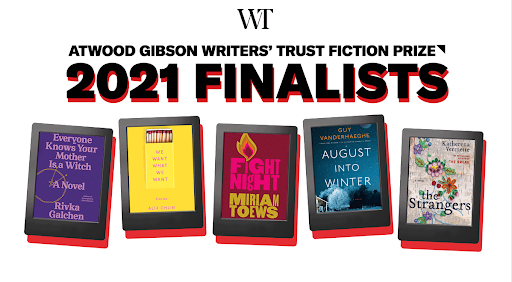

We're thrilled to speaking to four of the 2021 prize finalists today about their exceptional books and the experience of being nominated for one of the country's leading literary awards. Rivka Galchen is nominated for Everyone Knows Your Mother is a Witch (Harper Perennial); Alix Ohlin for We Want What We Want (House of Anansi Press); Guy Vanderhaeghe for August into Winter (McClelland & Stewart);and Katherena Vermette for The Strangers (Hamish Hamilton Canada). The fifth finalist, Miriam Toews, nominated for her novel Fight Night (Knopf Canada), was unavailable for interview at press time.

We hear from the finalists today about where their books first began, their favourite parts of the writing process (including when and how a book becomes like a horse), and the works of fiction they'd love to see readers discover.

The winner of the 2021 Atwood Gibson Prize will be announced on Wednesday, November 3 as part of the livestreamed Writers' Trust Awards.

Open Book:

How did your nominated book begin for you? Do you remember how the book first started or the very first bit of writing you did for it?

Rivka Galchen:

My 'happy place' reading had shifted over from cozy mysteries to historical biographies of scientists. It was comforting to read about difficult moments in history that were, well, over – that something else had followed them. That was how I learned of the true life story of the witch trial of the mother of the astronomer Johannes Kepler. I read a nonfiction book about the trial and I noticed that even from my 21st century perspective, there was a part of me reading the story as if to find out: was she really a witch? That ridiculous emotion frightened and interested me, and I became obsessed with following it out. Also I loved to think of this older woman, so capable, so remarkable in her own way – I began to think of Johannes Kepler as the son of this very wilful and super bright and slightly wild woman.

Alix Ohlin:

We Want What We Want is a collection of short stories that I’ve written over the past few years. The oldest story in the book, "Casino," is about a mother realizing that she may never see her runaway daughter again. Although I didn’t think of it as the start of a book at the time, this story turns out to contain many of the themes that tie the stories together: how our choices can have consequences we didn’t intend; how easy it can be to find ourselves separated from what we love; how the experience of loss can help us understand more about who we are.

Guy Vanderhaeghe:

When I was a very young boy I heard stories about the murder of an RCMP officer that had taken place in my hometown in the early days of the Second World War. The killer was the son of one of the most prominent members of the community and the scandal haunted the family for years. I had always harboured an inclination to write a novel with a similar premise: “respectable” young man commits an atrocity, although in the writing of August Into Winter the novel very soon departed from the actual incident, grew more lurid, bizarre, and baroque.

It took me decades to get around to writing the book. When I finally made a beginning, I opened with a scene in which a huge storm breaks over the town and the protagonist of the novel, Oliver Dill, has a vision of his dead wife. I thought this would be the first chapter of the book, but, in the end, it turned out to be the second.

Katherena Vermette:

It began right where it opens, actually – with the birth. It doesn't always happen that way, so this is more fluke than anything else. And this one really started at a festival (I think it was the FOLD), as I was listening to a writer talk about how their characters just went away after they were done writing the book. I thought "lucky bitch! mine are still bugging the hell out of me!" I always knew a bigger picture than the one in the first novel, but I guess I thought that was normal. That festival moment was when I thought maybe I should get the rest of that stuff down.

Open Book:

Where were you when you received news of your nomination? What was your reaction?

RG:

I was at home, it was early in the morning and I was very, very, very, very, very pleased and joyful.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

AO:

Since I live in Vancouver, by the time I checked my email in the morning I was lucky to have received a number of warm and lovely emails from friends and from the lovely staff at my publisher, House of Anansi. I always feel that it’s so hard to get much attention for short stories, and yet they are my favourite form to write, so I felt particularly thrilled to see WWWWW on this list.

GV:

I was in bed. My partner, who gets up very early, had been surfing the internet and saw the news. She came into the bedroom around five a.m. and said, "Guess who’s nominated for the Atwood Gibson Prize?" Still half-asleep, I said I didn’t have a clue. She said, "You."

What was my reaction? Surprise and delight.

KV:

This is pretty boring – I was on my phone doing the first email check of the day. I don't always keep track of when these things come out but this year everyone kept reminding me, like I wanted to know. I find it all terrifying to think I might not get on a list, even more terrifying that I might get ON one.

Open Book:

Is there a particular element of the fiction writing process that you find yourself most enjoying during book projects (whether research, first draft, editing, discussing the finished book after publication, or otherwise)?

RG:

At some point, a long project takes on enough momentum that it's on my mind when I'm walking to the subway, when I'm cutting an onion. That's when the project is a full time companion, living with you with the steady and powerful presence of a horse. That's a great time in the composition process.

AO:

My favourite part of the process is always when I haven’t written anything yet! I’m happiest when I’m daydreaming my way into a story. The work only imagined is always so perfect, flawless. Then inevitably once I start writing, I mess everything up and it’s a long, slow process to close the gap between ambition and execution as best I can.

GV:

What I enjoy most is the sentence tinkering stage. When I feel the big pieces are in place and that the narrative is securely anchored, I like fiddling with the prose, changing a word, recasting and rearranging a phrase, lighting up an image.

KV:

I love research, especially when I am playing around with eras and timelines. I like to listen to music from back when and look up chart lists and fashion trends and such. I really get a good sense of time's passing that way. I also love to do genealogies on everybody, and maps. All the stuff that's only really special to me, that you don't really need to know the story, I love that stuff.

Open Book:

Tell us about a favourite book or piece of fiction you've read that you feel may not have received as much attention as it deserved. What do you love about it, and why you would love to see others discover it?

RG:

I picked up Poison for Breakfast by Lemony Snicket (aka Daniel Handler) recently, because I had this feeling that maybe it would explain to me something of the feeling of what it is to read the news alongside a cup of coffee in the morning. It wasn't about that – but also it sort of was – and it described better than anything else I've ever come across the mysterious process by which a story or work of art comes together. I love kids' books, but was struck in how this particular Snicket book is more like literature as we generally conceive of it for adults. It kind of cured me of some melancholies, so I really recommend it, even as I wouldn't normally recommend a book by an author who maybe needs no help finding an audience!

Another book I loved recently – which had a related 'cure' quality, and a related essayistic style – was the magnificent Benjamin LaBattut book, When We Cease to Understand the World. It's difficult to describe, and it has a lot of mathematical and scientific biography in it, while being motivated by encounters with both evil and also profound light.

AO:

I think this is true of almost all books, if I’m honest, that I wish they got more attention. But the book I’ve most recently been pushing on every reader I know is Shirley Hazzard’s The Transit of Venus, originally published in 1980 and recently reissued. It follows two orphaned Australian sisters after they move to England in the 1950s. Hazzard’s work, both broadly political and sharply individual, is about what happens when the fates (like the stars) do and do not align for us. It’s not a novel you can read quickly because the prose is so finely wrought, but it’s wickedly funny. As soon as I finished it I flipped back to the first page and started it over so that I could experience it again, knowing what was coming.

GV:

I’ll mention a book that was published in the early 1970’s, Clark Blaise’s collection of short stories, A North American Education. Although highly regarded at the time, it appears to have dropped out of sight. Blaise is a beautiful stylist and a fantastic short story writer. If you care about good prose and short fiction, you need to read this book.

KV:

I really loved Ghost Lake by Nathan Niigaan Noodin Adler. It's an excellent collection of interconnected stories set in a beautiful, eerie location. The book itself is pretty gorgeous too. Great publication by Kegedonce Press.

__________________________________________________________

Rivka Galchen received her MD from the Mount Sinai School of Medicine, having spent a year in South America working on public health issues. Galchen completed her MFA at Columbia University, where she was a Robert Bingham Fellow. Her essay on the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics was published in The Believer, and she is the recipient of a 2006 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award. Galchen lives in New York City. She is the author of the novel Atmospheric Disturbances.

Alix Ohlin is the author of six books, including the novels Inside and Dual Citizens, which were both finalists for the Scotiabank Giller Prize and the Rogers Writers’ Trust Fiction Prize. Her work has appeared in The New Yorker, Tin House, Best American Short Stories, and many other publications. Born and raised in Montreal, she lives in Vancouver, where she chairs the creative writing program at the University of British Columbia.

Guy Vanderhaeghe was born in Esterhazy, Saskatchewan, in 1951. His previous fiction includes A Good Man, The Last Crossing, The Englishman's Boy, Things as They Are (stories), Homesick, My Present Age, Man Descending (stories), and Daddy Lenin and Other Stories. Among the many awards he has received are the Governor General's Awards (three times); and, for his body of work, the Pierre Elliott Trudeau Fellowship, the Writers' Trust Timothy Findley Award, and the Harbourfront Literary Prize. He has received many honours including the Order of Canada.

Katherena Vermette (she/her) is a Red River Métis (Michif) writer from Treaty 1 territory, the heart of the Métis nation—Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. Her first book, North End Love Songs, won the 2013 Governor General’s Literary Award for Poetry. Her first novel, The Break, was a national bestseller and won several 2017 awards, including the Amazon First Novel Award, Margaret Laurence Award for Fiction, Carol Shields Winnipeg Book Prize, and McNally Robinson Book of the Year. She lives with her family in a cranky old house within skipping distance of the temperamental Red River. The Strangers is her second novel.