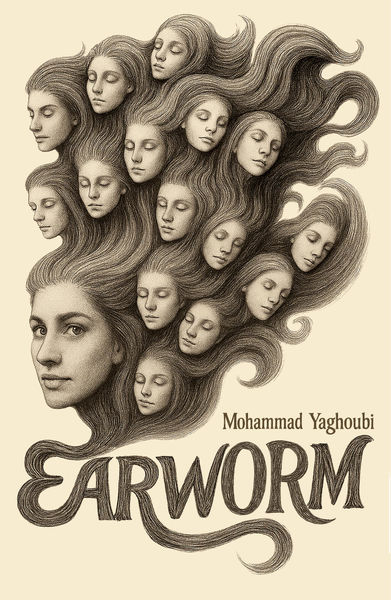

The Captivating Thriller EARWORM Chronicles a Young Woman's Battle Against Oppression

In his spectacular new play, Earworm (Playwrights Canada Press), Mohammad Yaghoubi delivers a haunting and deeply human story about memory, trauma, and the uneasy search for freedom. The novel follows Homa, an Iranian refugee living in Canada with her teenage son, as she tries to rebuild a life far from the violence she fled in her homeland. Yet, even in safety, she cannot escape the past. The voices of those who tortured her still echo in her mind, and the peace she longs for remains just out of reach.

When her son begins dating a young woman whose father is a devout Islamist, Homa’s fragile calm begins to crack. What follows is a gripping and psychologically charged story that examines how oppression and fear can follow us across borders, and how speaking out can become both a lifeline and a danger.

Written in solidarity with the 2022 Woman, Life, Freedom movement, Earworm is as political as it is personal. Yaghoubi brings sharp insight and empathy to a story about exile, identity, and resistance, crafting a powerful reflection on what it means to live freely while carrying the weight of the past.

We're delighted to share this enlightening and inspiring Behind the Curtain interview with the author!

Open Book:

How did this play first come to life for you? Do you remember the first bit of writing you did for it?

Mohammad Yaghoubi:

Earworm started for me, inspired by a few shocking, real-life events. In recent years, a lot of people in the Iranian-Canadian community—immigrants who fled an oppressive Islamic regime—have noticed more and more folks here in Canada who are tied to that regime. I'm one of those immigrants; I left Iran in 2015 to put distance between myself and those years. It was a genuine shock, a few years later, to see individuals in Toronto’s Iranian community who were openly connected to or supportive of that oppressive government. They were and are organizing religious gatherings exactly like the ones back in Iran, right here in Toronto.

For many Iranian immigrants, seeing these figures establish themselves here while still aligning with the Islamic Republic is deeply alarming. The real alarm bell went off in February 2022, when a viral video circulated showing Morteza Talaei, the former chief of police in Tehran, working out at a gym in Richmond Hill. Talaei was known for launching a special unit in 2006 known as the “morality police,” which later transformed into the Guidance Patrol—tasked with arresting women wearing supposedly un-Islamic clothes.

Inspired by these events, I started writing with a question I couldn’t let go of: What if an Iranian refugee woman who’d been imprisoned in Iran suddenly recognized the man who once interrogated her—here, in Toronto? That “what if” got tangled up with another question I’d carried for years: What happens when you realize the father you idolize is also capable of immense cruelty toward others?

The very first bit I wrote was a scene where Homa, the protagonist, and her son are getting dressed to visit his girlfriend’s family. That scene eventually became the third scene in the play.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

Did the script change in any way once you were rehearsing?

MY:

Yes, it changed a lot during the development phase and rehearsals before its premiere. The biggest change was in the ending, which was deeply influenced by the nationwide uprising known as the “Woman, Life, Freedom” movement against the Islamic regime in Iran. This movement was sparked when Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Iranian woman, was murdered in Tehran by the “morality police” on September 16, 2022. The solidarity of Iranians worldwide was a major source of inspiration for me.

The first draft of the play came from a place of despair, but the uprising changed something in me and in the story. The first draft was a one-act piece. Just before development, it became a two-act play, and during rehearsals, the ending changed yet again. Honestly, I have a bit of an obsession with rewriting! I even number my drafts at the bottom of each file just to keep track.

The version we performed at Crow’s Theatre in January and March 2024 was version sixty-five. After that, before Playwrights Canada Press published it, I made a few more edits—trimming some parts and adding a few new lines. The version that’s about to be published is version sixty-eight.

OB:

In your opinion, how does one go about writing great and memorable characters for the stage?

MY:

When it comes to creating characters, I like to share a piece of advice from Nadine Gordimer, the Nobel Prize–winning author, because I think it’s the best advice about character. She once said that when she was a very young and inexperienced writer, her characters were “ideas with legs,” and that’s why they didn’t feel real. She later understood she had to write “legs that think.”

Of course, novelists have more space to explore a character’s inner world, but on stage, we get to know characters through conflict and interaction. To write memorable and believable characters for the stage, you need to put them in confrontation—with another person, with an unexpected event, in a situation outside their comfort zone, or up against a belief that challenges their own.

OB:

Do you feel your work has changed in any way through your writing life and career?

MY:

Definitely! The biggest change is simply that I no longer have to censor myself. In Iran, every play needed approval from a government censorship committee. What audiences saw on stage was always a wounded version, first cut by the official censors, and then by the writer’s own self-censorship.

For one of my plays, Writing in the Dark, we had to present the script to the censorship office six different times because they refused to approve it and kept demanding more cuts. Here in Canada, I don’t have to deal with that at all. For example, Earworm is full of moments that would still be impossible to stage in Iran. Basic things are banned there: female performers must wear the hijab, men and women aren’t allowed to hug or kiss, and certain words can’t be spoken on stage.

I spent so much of my time in Iran negotiating with censors or trying to outsmart them by inventing coded language. For example, in my play Drought and Lies, whenever a performer needed to say a forbidden line, I asked them to replace it with “twenty-five.” So a line like “kiss me,” which couldn’t be said on stage, became “twenty-five me.” When the committee asked what “twenty-five” meant, I told them, “It’s just a number.” They accepted it! After the run, I explained in an interview that “twenty-five” referred to Article 25 of the constitution, which prohibits censorship. After that, I was banned from using that trick again.

Eventually, I was openly targeted as a dissident playwright and director, and I wasn’t allowed to negotiate anymore—I just had to cut whatever they demanded. That’s why I value the freedom of working in Canada so deeply. Writing here, for me, is a process of getting all that censorship out of my system. It’s like unlearning self-censorship and relearning how to write freely.

Formally, my writing has also evolved. I’ve become more interested in interactive structures and creating a direct relationship with the audience. And since moving to Canada, I’ve started writing bilingual plays in both English and Farsi, because I want to speak to two communities: English-speaking audiences I’m still getting to know, and Persian-speaking audiences I want to stay connected with.

OB:

How would you define the role of theatre in society?

MY:

If we think about the fact that theatre, as we know it today, rooted in the scripted traditions of ancient Greece, has existed for over two and a half thousand years, that alone proves its essential role in human life.

For me, theatre is both a refuge and a form of activism. I deeply believe it’s born out of necessity and social responsibility. It’s where we come together to see reflections of ourselves and others, to ask essential questions, to face the things we usually hide or are afraid to express in everyday life. It’s a civilized way to challenge power, to expose injustice, and to promote beauty and kindness. It’s a place for empathy—for becoming “the other,” for living through someone else’s experience and truly understanding them.

In a world ruled by capital, theatre reminds us that all you need to create is living human presence. Theatre is also an act of resistance against isolation. As the digital world expands, keeping us entertained but isolated in our rooms, theatre invites us to gather again—to witness real artists creating magic with nothing but their bodies, their voices, and their courage.

Even in the worst-case scenario, if one day the digital world takes over completely and no one comes to see theatre anymore, as long as there are a few people who still want to gather and create something together, theatre will survive.

That’s the essential difference between theatre and, say, film. A film is made to be seen. Theatre is born from the need to gather, to coexist, to share space. Being seen by an audience is secondary. Theatre can survive with just a few living people in a room, creating something from a written text or inventing something entirely new.

Maybe it’s a small group rehearsing Antigone, trying to understand the script, discovering those characters within themselves, embodying them, and understanding “the other” through words written more than two thousand five hundred years ago.

It is in this small, sacred act of gathering that theatre finds its eternal life. Isn’t that wonderful?

_____________________________________________

Born and raised in Iran, Mohammad Yaghoubi is an award-winning playwright, director, and screenwriter. He moved to Canada in 2015 and co-founded the Toronto-based NOWADAYS THEATRE company in 2016. His plays have been translated into seven languages and have been produced worldwide. His other notable works produced in Canada include Heart of a Dog (Next Stage Theatre Festival, 2022), Winter of 88 (Next Stage Theatre Festival, 2020), The Only Possible Way (Canadian Stage Company, 2019), Dance of Torn Papers (Dancemakers, 2018), and A Moment of Silence (SummerWorks Festival, 2016).