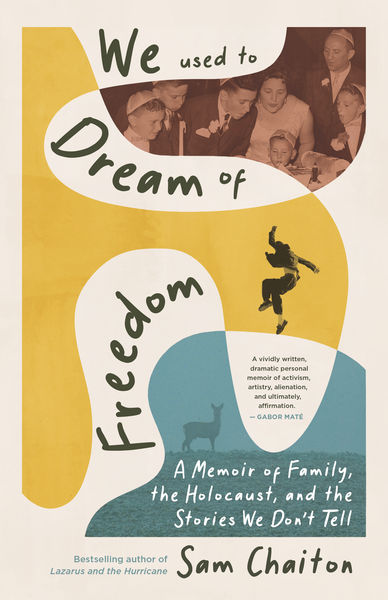

Toronto artist Sam Chaiton Explores How Profound Trauma Shapes a Famiy in his new Memoir, We Used to Dream of Freedom

Our featured author today is no stranger to the trials and tribulations of oppressed peoples, and his actions throughout a long and varied artistic career bear that out clearly. Perhaps most known for being involved in freeing Rubin "Hurricane" Carter from wrongful imprisonment, Toronto author and social justice advocate Sam Chaiton famously penned the bestselling non-fiction title Lazarus and the Hurricane, which chronicled that historic event.

In his new memoir, We Used to Dream of Freedom (Dundurn Press), Chaiton goes back even further to the origins of his family, and their immigration to Canada after suffering at the hands of the Nazi's and surviving Auschwitz, amongst other notorious prison camps. The author and his brothers knew some of the story, but their parents would not talk about much of it, and the legacy of that trauma shaped all of their lives.

Exploring the gravity of this knowledge and history, Chaiton grapples with these truths and ponders what family is and could be, depending on how survivors cope with their trauma. And, he takes the crucial step to show how second-generation survivors can take responsibility for traumatic past events to find ways to help and heal others, and themselves.

Read more about this deeply moving memoir in this special True Story Nonfiction interview with the author.

Open Book:

What was your research process like for this book? Did you encounter anything unexpected while you were researching?

Sam Chaiton:

A good portion of my research for We Used to Dream of Freedom, a memoir, came from plumbing the depths of personal memory. An ample section on my childhood, going back more than sixty years, required fact checking of dates, names, and places to corroborate the detailed images that remained with me despite time’s passage. When my version of events was challenged by one of my brothers, I would check with other relatives, search online, seek out old photographs and press accounts, and make corrections where necessary.

There were questions that called for major research into outside sources. One of them yielded an extraordinary find. How were my parents and two older brothers able to immigrate to Canada after the War? I read the seminal book None is Too Many about Jewish immigration from Europe (and lack thereof) into Canada in the 1933–1948 period. The Mackenzie King government was less than welcoming until a group of clothing manufacturers and union leaders made it known that the Canadian garment industry direly needed skilled workers for their factories. The Displaced Persons (DP) camps in Europe were full of tailors and seamstresses that exactly fit the bill. Approval was given to allow into Canada 2500 garment workers, the majority of whom were Jewish. This became known as the Tailor Project. My father was one of those tailors.

The Ontario Jewish Archives proved to be a treasure trove of information. Among the papers of one of the garment manufacturers sent to Europe on a mission to find tailors, I came across a carton of used airmail envelopes that had been torn open. All the envelopes were empty except for one. I examined it carefully and gasped. It was addressed to my father in the Belsen DP camp, and postmarked Toronto, Ontario, July 17, 1947, 2:30 pm. The return address was N. Kirsh, 337 Brunswick Avenue, Toronto. My hands began to tremble as I pulled out the letter. It was handwritten in cursive Yiddish writing, the ink blue and smudged.

“Dear Luba,” it began. Luba was my mother, and the letter was from her aunt in Toronto, telling her to save themselves by having my father apply to the delegation that was shortly to appear in Europe in search of qualified tailors for Canada. I cried, realizing I was holding this precious correspondence that my father and mother had once held in their hands, a letter that would change their lives and result in my being their first child born in Canada.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

OB:

What does the term creative nonfiction mean to you?

SC:

Creative nonfiction is nonfiction that isn’t boring, that doesn’t drown you in dry fact but enlivens a subject with metaphor, unexpected juxtapositions and big ideas. Whether it be a work of biography or memoir, history, psychology, science, or personal essay, it moves and transforms you, intellectually and emotionally. For me, creative nonfiction is literary nonfiction. The prose is elevated, poetic even, the author making judicious use of techniques that are more commonly found in fiction.

OB:

What do you do if you're feeling discouraged during the writing process? Do you have a method of coping with the difficult points in your projects?

SC:

If I feel discouraged during the writing process, which I invariably do, I resort to a playbook of strategies. If something is not working for me, even at the level of the sentence, I read it aloud to myself or a trusted outside ear, hoping for some new insight. Or I come at it from an opposing angle. Or I just get depressed and validate my imposter syndrome by ceasing to pretend that I am a writer.

The most successful strategy, I find, is to surrender: move away from my desk, have a nap, sit in meditation, walk in nature. Let it go. Resume when I’m refreshed and confident that a solution will appear, despite my misgivings.

OB:

Do you remember the first moment you began to consider writing this book? Was there an inciting incident that kicked off the process for you?

SC:

We used to Dream of Freedom had its origins on Easter Sunday, ten years ago, the day that Rubin “Hurricane” Carter died. On hearing the news, I felt an immediate and overwhelming need to write another book. It was going to be something new, something I hadn’t written about in Lazarus and the Hurricane.

I sat down at my desk, pencil in hand, a blank notebook in front of me. Before I knew it, several pages were filled. Of the ideas I noted down, most seemed to apply to my parents, who had also been unjustly imprisoned. My mother and father were concentration camp survivors, both having been prisoners in Bergen-Belsen. Their incarceration, like Rubin’s, was based on racism rather than reason. But unlike Rubin’s story, which had come to be known world-wide, their stories remained hidden, even from my brothers and me. My parents’ internment also included a period in Auschwitz, a fact I only recently learned, years after their passing.

The memoir began to take shape when I asked myself why, despite being eager to delve into Rubin’s history, I had assiduously avoided my own. I realized there was much I needed to probe, including why I disappeared from my family for nearly two decades. Further questions arose. How had my parents’ Holocaust experience — and their silence about it — factored into that rift? And what role did my work to free the Hurricane play in my ability and drive to unearth family history and expose it to the healing light of day?

Writing We Used to Dream of Freedom became a voyage of self-discovery. It began on an emotionally-charged day. Loss was its origin; curiosity, its impetus; distance and time, its opportunity for clarity.

OB:

Did you write this book in the order it appears for readers? If not, how did it come together during the writing process?

SC:

This memoir was not written in the order it appears for readers. For the most part, it is told chronologically. But it was set down according to the bandwidth its component events occupied in my memory. Top of mind was how I came to discover the secret of my parents’ histories, and what that secret was. This was for me the most dramatic and affecting part of the story I wanted to tell. So that’s where I started.

I write sparingly. When I jot down a scene or vignette, I quickly go from A to Z. I let it gestate overnight, then review. That’s when I realize that in-fill is needed. Details soon begin to emerge to fill in the blanks: place, weather, characters, clothes, facial expressions, dialogue, colour. And day after day, I keep building, editing as I progress, until the entire edifice is complete. It’s a process of accretion.

But this edifice, I discover, cannot stand on its own. It needs scaffolding, context for a reader to appreciate its significance, its beauty, precarity, and serendipity. Add some flying buttresses and more in-fill. After what seems like years of construction, there’s a book.

__________________________________

Sam Chaiton, the middle son of Holocaust survivors, is one of the Canadians who helped Rubin Carter gain his freedom. Co-author of the international bestseller Lazarus and the Hurricane, he is portrayed in the film The Hurricane by Liev Schreiber. A founder of Innocence Canada, Sam lives with his partner in Toronto.