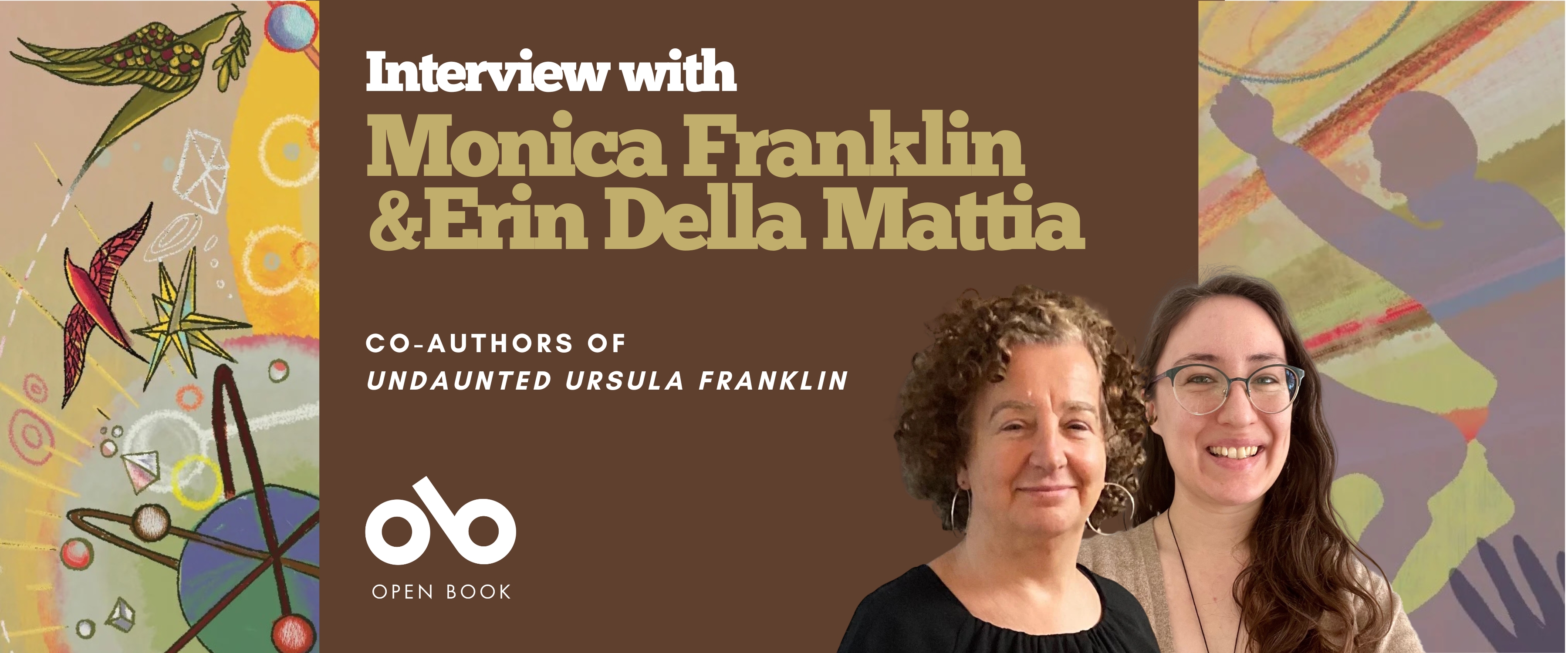

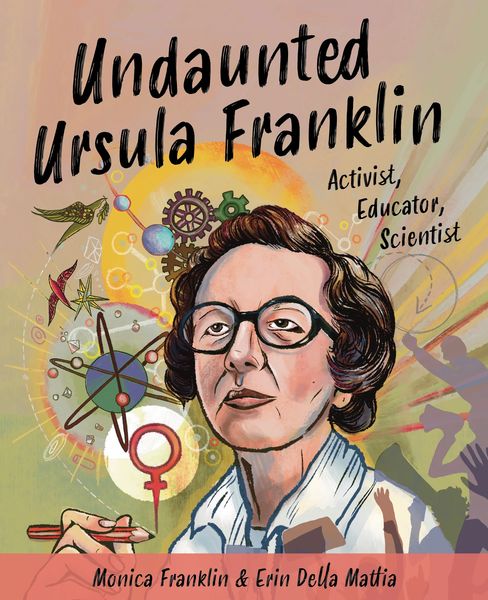

Undaunted Ursula Franklin Honours and Celebrates a Truly Remarkable Scholar, Scientist, and Activist

“Peace is not the absence of war, peace is the absence of fear.”

The above quote comes from Ursula Franklin, the titular character in a new book for young people that explores the life of this fascinating, resilient, and brilliant woman. Born in Germany with Jewish ancestry, Franklin survived the Holocaust and became a physicist and engineer in a time when women simply weren't allowed into the academic world. The events of Franklin's past shaped her into a fierce advocate for equality, peace, and the protection of the environment, a legacy that carries on today.

It's no surprise then that such a powerful figure should receive their due, and some of that recognition comes in Undaunted Ursula Franklin (Second Story Press), a new book for young people from Monica Franklin (Ursula's daughter) and Erin Della Mattia. This title chronicles Ursula Franklin's vast achievements as a scholar, scientist, and social justice advocate, along with the care that she gave as a mother.

This new book is an exploration and celebration of a women who received both the Order of Canada and the Pearson Peace Medal, and who has a Toronto street and school that carry her namesake, and that serve as places where children can remain undaunted and sheltered during the challenges of their daily lives.

We're delighted to share this Kid's Club BFYP interview with both of the authors of Undaunted Ursula Franklin, right here on Open Book!

Open Book:

Tell us about your new book and how it came to be.

Erin Della Mattia:

Undaunted Ursula Franklin tells the life story of a trailblazing feminist scientist from the perspective of one of the people who knew her best—her daughter, Monica. In the face of Nazi soldiers, chauvinistic colleagues, and RCMP spies, Ursula persevered in doing what she thought was right and standing up for those harmed by war and discrimination. Ursula defied the odds as a Holocaust survivor and refugee in Canada, becoming a role model and mentor for girls and young women in STEM.

Monica had already written a full draft before Second Story Press invited me to come on board this project. After some preliminary discussions, we worked together to substantially rewrite the manuscript, drawing out the narrative of Ursula’s life and creating some pieces of socio-historical context so that readers could better understand the world that Ursula lived in. (We nearly doubled the original word count!) Monica and I focused on doing justice not just to Ursula’s life but to the ideas that fueled her feminist activism and scientific work. Sharing her ideas with young people was one of the main things that motivated me through the writing and revising processes.

Monica Franklin:

As my mother got older and especially after her death in 2016, I thought more and more about what an interesting life she had led. She had been “the first woman” in many of the things she had done. She had been a student, a scientist, a Holocaust survivor, a teacher, an anti-war and pro-peace activist, a feminist and a mentor to many women and young people. She had even been a school and a street! Ursula Franklin Academy is a public high school in Toronto and Ursula Franklin Street is in downtown Toronto, near the University of Toronto where Ursula spent most of her career, in the Faculty of Engineering. She received a lot of awards and honours, like the Order of Canada, the Governor Generals Award and the Pearson Peace prize as well as many honorary degrees from Canadian universities.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Throughout Ursula’s life, she made decisions and lived according to her very strong principles and beliefs. She was recognized and awarded but people don’t know that much about her. Considering that she was a public figure, she was a very private person. This book was my opportunity to tell readers her story: who she was, what she did and why, the challenges she faced and how she overcame them. I also did not want the things she fought for to be forgotten.

OB:

Is there a message you hope kids might take away from reading your book?

EDM:

There’s an anecdote about how Ursula once met with a student who was torn between pursuing feminism and pursuing science in her studies. Ursula asked her, “Why not do both?” It can be hard to envision how you can blend STEM with feminism or other kinds of activism, but this is something Ursula did her whole life. She believed that we could build a better world by combining our strengths. I hope Undaunted Ursula Franklin shows young readers that they, too, can use STEM within their activism, and vice versa.

MF:

I would like kids to take away from the book that it’s really important to get involved in the world around them, especially via their every-day lives- in their school or with their family or friends or in the community. It’s a way of learning, contributing and making a difference. Ursula thought that any decision that affects people needs to have the input from those who are affected- whether it’s a big thing like a government position or policy, or something smaller like how high the building on the corner should be or even smaller than that, like your school’s dress code or how kids behave in the lunchroom or on the playground. If it affects you, you should have an opinion and should feel like your opinion is valued and respected.

I would like kids to use Ursula’s example to speak up and take positions based on their beliefs- what they know is right and wrong. It might not be popular or what all their friends are doing. What Ursula did and said was often not popular at the time. Many people disagreed with her, including her co-workers and bosses, but she persisted. Some of them even came to understand and agree with things she was saying.

I would also like kids to realize that some of the things they may take for granted- like women studying sciences, math and technology or even women having jobs, much less being the mayor of a big city like Toronto- weren’t always that way. Many women and men struggled to make the changes we now see in our society. Ursula was one of them.

OB:

Did the book look the same in the end as you originally envisioned it when you started working or did it change through the writing process?

MF:

I had the “big picture” of the book and what I wanted to say in my mind when I started. I had a lot to say though and a lot of material. I had to do research about things I did not know, like my mother’s early life and what happened to her in Germany before she came to Canada. She spoke very little about that: her focus was on the “here and now”: her life in Canada. For many other things I was lucky because my mother wrote and spoke out quite a lot, especially about things that were important to her. There were books and articles I could refer to. There were also things that I knew myself or remembered. It was a challenge though to figure out what to say (and how much), how to say it, what to include and what to leave out. I wrote a lot of drafts. I was told I was trying to do too much and say too much. I was not sure how readers today would relate to my mother who was born more than 100 years ago, her experiences in Germany during the Holocaust and afterwards and then her life in Toronto and at the University in the early 50s and 60s. I wasn’t sure they could relate to me as her daughter and what I experienced alongside of my mother-- because this is my story life too. In the end, the input of my co-author Erin in the process was really important and helped make the book better and stronger.

OB:

What was the strangest or most memorable moment or experience during the writing process for you?

EDM:

I’m the type of writer who likes to throw things at the wall and see what sticks. This means I sometimes come up with outlandish ideas. My co-author Monica is much more grounded and logical, so she often had to rein me in whenever I went too far. She would say to me very calmly, “No, Erin, that’s too melodramatic.” I could only laugh and agree. And then come up with another idea. I wasn’t sure what it would be like working with another author, but I think our skill sets were very complementary, which helped the writing and revising processes go pretty smoothly.

OB:

How do you cope with setbacks or tough points during the writing process? Do you have any strategies that are your go-to responses to difficult points in the process?

EDM:

Positive thinking, or even just silencing the negative thoughts, is a useful strategy for me. I do this by taking something that feels negative and flipping it on its head. For example, I believe that, in writing, every seeming problem is actually just an opportunity waiting to be explored. (I’m an editor too, and this is something I say to authors all the time.) In fiction, when you’ve hit a wall in the plot and can’t seem to move forward, go back a bit and find a spot where your character makes a critical decision. Have them choose the opposite choice. Write from there. In nonfiction, move sentences or paragraphs around to change up the flow. New thematic connections may emerge that help you clarify your ideas for that chapter. In other words, every setback is a chance to try something new. Or take a break. Breaks are good, too. Refresh your mind and refill your creative well.

OB:

Do you feel like there are any misconceptions about writing for young people? What do you wish people knew about what you do?

EDM:

I think there are certain misconceptions about who these young people are. Sometimes I see writers (and readers) who have a sort of “normative,” middle-class perception of young people, but real kids are much more complicated than that. They experience difficult things in life. War, displacement, abuse, discrimination, mental health struggles…. A lot of kids have experienced these things themselves, or they know someone who has. (Yes, even “sheltered” middle-class kids.) So, when we write about these topics, we have to assume that kids already have some knowledge about or experience with them. Never talk down—or write down—to kids. Meet them where they’re at—they might surprise you.

MF:

I think there is a misconception that we shouldn’t write about “difficult” things- like the Holocaust, prejudice or discrimination, racism or sexism- and especially in a non-fiction format, because kids shouldn’t be exposed to those things or can’t relate to them.

I don’t agree. Increasingly kids are coming to Canada from all parts of the world. Many have experienced injustices and seen things kids born in Canada can’t even imagine. Also, kids today are exposed to difficult and challenging topics via the internet. As well, they may have experienced prejudice or discrimination in their own lives: in their classrooms, within their families and with their friends. It’s important to talk and write about these topics. I think it’s helpful to see how others experienced these issues and how they responded. Holocaust survivors, like Ursula, often had very strong moral principles and attitudes that shaped what they did in the rest of their lives. I don’t think you can talk about Ursula and all the things she did without knowing about what she experienced in her life- like the Holocaust, prejudice, discrimination and sexism. Ursula didn’t want to be defined by the Holocaust, but it was part of who she was and how she responded to the challenges she faced.

OB:

What's your favourite part of the life cycle of a book? The inspiration, writing the first draft, revision, the editorial relationship, promotion and discussing the book, or something else altogether? What's the toughest part?

EDM:

Oh, the inspiration stage for sure! I love ideas! I love daydreaming and imagining all the possibilities without being committed to any of them. The tough part is actually harnessing those ideas and making something of them. The commitment. Doing the work of transferring things from my brain to the page in a coherent way. My way of dealing with this is to remind myself that other people are relying on me to do this work. Once I understand that, there is no choice but to get it done.

MF:

I think I like the beginning part best, when you are planning the story and thinking about how to put it together. I had a lot of things I wanted to say, a lot of ideas and a lot of material. Trying to figure out what to say, how to say it and where in the book to talk about it was a little like putting together puzzle pieces. Would this idea or story work better here? Should I make this section bigger or smaller? Would this part fit better in this section or in that one? Should I include this story or idea or is it too much? Does this add to the story or is it a distraction? How can I make this part more personal and less like a history lesson? And then everything gets changed and adjusted by the input of others- in my case my co-author, publisher and editor. There are many drafts and revisions and revisions, but I do have a soft spot for the first and early versions of the book! They show what I was trying to do and what I was thinking in the beginning.

OB:

What are you working on now?

EDM:

My mind is always scattered among several projects, but one of my current projects is a YA novel about an Italian-Canadian family living in Toronto during World War II, as told through the perspective of the teenage daughter. It deals with how discrimination and internment impact the family. I’m in the research stage for that novel. I’m also trying to develop a coherent story outline for an upper-middle grade speculative-historical novel about witches. My ideas keep running away from me though, haha.

__________________________________________

Monica Franklin is a retired lawyer living in Toronto with her family. She is very pleased that her children were able to know and learn from their inspiring maternal grandmother, Ursula Franklin. It was only later in life that Monica came to learn the extent of her mother's achievements and the obstacles she overcame.

Erin Della Mattia is a writer and editor from Brampton, Ontario. Her fiction has appeared in The Puritan and in the fairy tale anthology Sharper Than Thorns. Although her collection of book ideas grows ever larger, she can usually be found elbow-deep in the brilliant mire of someone else's manuscript.