"We are What We Read" Jason Camlot and J.A. Weingarten on the Power of Exploring Personal Libraries Throughout History

Our bookshelves say a lot about us. They reveal what fascinates us, what we value, and where we've been. And so the personal libraries of literary, political, and historical figures can function as a unique lens to reveal what made someone tick.

In Unpacking the Personal Library: The Public and Private Life of Books (Wilfrid Laurier University Press), editors Jason Camlot and J.A. Weingarten delve into the libraries of a variety of influential people, from prime ministers to Virginia Woolf. There's also content to delight CanLit lovers, with views into the bookshelves of the likes of Sheila Watson and Al Purdy.

The book contains celebrated anthropologist and writer Alberto Manguel's account of the Library of Alexandria, discussions of how public libraries have co-existed with personal ones throughout history, and how the public and private lives of books influence us in myriad ways as a society.

With the history of books and libraries being deeply caught up in the history of class, race, equity, and access, Unpacking the Personal Library is both a glimpse into our most personal spaces and into the way our collective culture is shaped by the written word.

We're speaking with Jason and J.A. today about their book, as part of our anthology series for editors of essay collections. They tell us about the CanLit icon whose personal library first sparked the idea for the project, how there is "always a mystery surrounding the personal library", and how a hopeful long-shot request to a contributor paid off.

Open Book:

Tell us about the new book and how you became involved with it.

Jason Camlot:

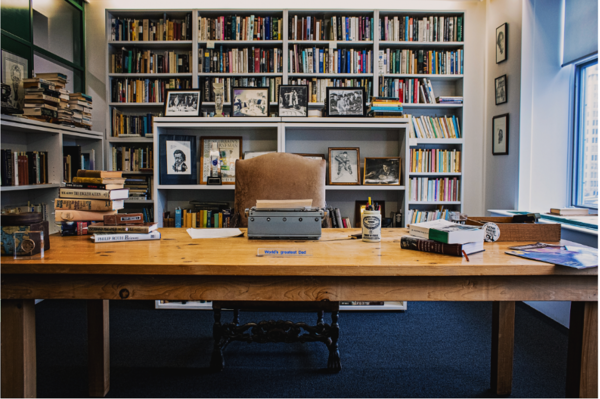

The story behind this book goes back to around 2012 when I was Chair of the Department of English at Concordia University. One day, the Dean of Arts and Science called me and asked if we might be interested in acquiring the personal library of Mordecai Richler. This had been offered to Concordia via the Provost who was friends with the lawyer of the Richler estate, and had been seeking a home for this collection for quite a long time. I was aware of some little-used space adjacent to my department that might hold such a collection (although at this time I had no idea of its size or scope), so I suggested that we would be interested in this acquisition if that space could be properly renovated to accommodate it. From that point, the discussions and negotiations surrounding the acquisition of an author’s personal library to be stored in a departmental space (not in our Special Collections, which would have no room for such a collection) were on. Eventually, I was given funding from the university and Richler estate to do a first cataloguing of the collection, which was boxed and in storage at Vêtements Peerless Clothing Inc., whose owner was an older friend of the Richler family. In June and July of 2013 I led a small team of students and librarians to Peerless and for about a month we punched in at 8am with the hundreds of factory workers who worked there making men’s suits, and we spent our days unpacking each of the 157 2-cubic-foot boxes that held over 5000 books, as well as many feet of paper ephemera, typescript, posters and photographs, objects and realia.

Eventually, that collection was moved into the renovated space at Concordia, catalogued further, and it became the centre of a research program that I called “The Richler Library Project” – a set of projects that were designed to think about the significance of author libraries as messy collections that often get dispersed and lost as coherent assemblages for research. With a grant from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada, I was able to develop this project in a whole bunch of interesting ways, including completion of a thorough item level-cataloguing of the Richler library collection, collecting oral histories with the Richler family and friends around items in the library collection, developing an online database from which the collection could be searched, and, the development of projects that expand beyond this particular collection to thinking about the nature of personal library collections and other forms of collection as objects of research. I co-hosted a series of conferences that explored such questions, and one of them focused specifically on the presentation of research about private and personal libraries as they may relate to other kinds of libraries. I co-hosted one such conference with Jeff [J.A.] (held in June 2016) called “The Promise of Paradise: Reading, Researching, and Using the Private Library.” The research presented at this conference provided much of the material that was then developed over several years into the chapters of Unpacking the Personal Library. Other publication projects have emerged from this work, including a forthcoming co-edited collection called Collection Thinking, a forthcoming special dossier on Richler in Canadian Literature, and a digital publication called Shelf Portraits, in which living Canadian authors provide works in any genre that reflect upon the significance of their own personal libraries, with home-made “shelfies” – photos of their shelves that they have taken themselves.

So, this extensive study of personal libraries as fluid entities quite appropriately arose from a serendipitous request to save the materials that constituted a single author’s library from being broken up, sold off, or thrown out.

OB:

What drew you, personally, to this subject matter, and why was this the right time to gather pieces in book form to discuss it?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

J.A. Weingarten:

When I was a Ph.D. student at McGill, around 2010, I had been studying Canadian Literature, and I found out that the major Canadian poet (and political figure) F.R. Scott’s personal library was stored at the campus’s main library. I thought it would be interesting to see what Scott owned, to touch the same books he touched. My initial thought had been to give a conference paper on the collection, and I was a bit too presumptuous about what I’d find in the library: when I sent off that conference proposal, I had expected to find a wealth of annotations and notes in Scott’s books. I thought, for sure, I’d be able to make some interesting comment on what he read and how he read it. But by the time my conference proposal was accepted, I realized that his poetry and fiction books were actually almost never annotated. Naturally, this caused me quite a lot of panic as the conference date loomed... but I did what all academics often do: instead of presenting a paper on what I found, I presented a paper on why I couldn’t find what I expected to find.

Oddly enough, I think that was a much more interesting paper than the original one I’d hoped to deliver, and it made me aware that personal libraries are not always straightforward in terms of their message or meaning. This led me to keep working on personal libraries, which eventually (five years later, in 2015) led to a FRQSC Postdoctoral Fellowship under the supervision of Jason Camlot at Concordia University. In 2016, we co-organized a conference on personal library collections across the world, which became the basis for this book.

The book, I think, shows a much bigger picture of what I realized back in 2010: a personal library is intensely personal, and so they are wildly enigmatic subjects of study. There is always a mystery surrounding the personal library, where an outsider to the collection might find themselves asking, “What’s here? What’s missing? What meant the most to the collector? Why did the collector keep these unread or unopened books? What do the inscriptions in the books tell us? What does the condition of individual books tell us? How do we use the library to put together pieces of the collector’s own life?”

I found those questions fascinating, because I really do believe (as I say in the book) that we are what we read.

OB:

How do you view the pieces in the book as speaking to each other?

JAW:

I think Unpacking the Personal Library is a very unique perspective on book collecting in so far as it offers a consistent and broad message: personal libraries take on unimaginably diverse forms. Each chapter of the book speaks to that central point by showing that the idea of “value” when it comes to books is very, very subjective. For instance, one chapter in our book shows how some “remaindered” books from libraries sometimes become the foundation of “protest libraries” that have, at particular moments in history, fueled revolution in the USA. In my chapter, I point out that it is impossible to donate annotated books, because even though these books are of great value to me (since they contain my thoughts on the page), they are sullied beyond usefulness to any other reader. There are all kinds of ways in which people conceive of “value” when it comes to the books they collect or that others collect, and I think that’s one of the central issues in this book, and it’s part of a question that every chapter tries to answer in some way: how and why do books become objects of personal, familial, community, or sociocultural importance?

OB:

What do you hope readers will take away from these pieces, after having read them all? Is there a question you set out to address or delve into through these works?

JC:

As I began to explain above, the idea of the library as an ever fluid and circulating entity was one of the exciting concepts that certainly informed my introduction to the collection, and that gave shape to the book as a whole. The long development and collaboration with our contributors allowed us to produce an original study that approaches the library as a living embodiment of material, political and aesthetic forces, and that expands our understanding of what libraries are and can be within an array of historical contexts. I am very proud of the collection that we have been able to assemble because I think it makes a significant contribution to library studies, book history, cultural history, digital humanities, cultural studies, literary studies, of course – so, to a very wide range of disciplines for which the library remains an important kinds of cultural assemblage to think about.

A few key questions we hope our book will get readers thinking about are: what is a library? what is the cultural significance of libraries as they exist and change over time? what are the possible futures of libraries as we move further into digital systems and processes for accessing and using printed information; so, what is the future of libraries?

OB:

Did you get to work with any writers you already knew for this project? Tell us a bit about those pieces and how you worked with the writers you knew prior to this book?

JAW:

Many of these contributors were friends from across the country: Cameron Anstee, Nicholas Bradley, Linda Morra, and Bart Vautour are longtime friends of mine. Nicholas was actually my TA when I was in undergrad, and has since become not just a good friend, but also one of my biggest supports throughout my career thus far. The other contributors were extremely diverse and talented scholars from all over who attended our conference in 2016, and we loved their research and papers so much that we thought it was essential to get us all back together to do a book.

The big thrill for me, understandably, was to rope Alberto Manguel into writing the first chapter of the book. My wife, Aislinn, was visiting me in Montreal when, totally unexpectedly, Manguel kindly replied to my long-shot invitation to participate. I still remember Aislinn exclaiming, “YOU HAVE AN EMAIL FROM ALBERTO MANGUEL?” She’d read his work since she was a little girl; I think she was even more excited than I was. One of the incredible things about working with Manguel is the encyclopedic and yet completely reader-friendly way he unpacks his mind (and, of course, his library). Here is a true intellectual whose cavernous mind holds more than I can imagine, and yet he’s able to entice any reader, any audience. I’ve always wanted to do a book that would reach a larger audience in terms of its readability, and I think Manguel’s presence in the book is a symbol of that goal; his beautiful prose is a wonderful opening note for the book, and it meant a lot to me to work with him.

And it would be in poor taste to neglect to mention what it was like to co-edit and write with Jason. I was very lucky to work with him on this book, and he has written a stellar and extremely engaging introduction to the book that sets up all of the questions we’ve talked about over pints and coffees for years. It’s rare to have such synergy with a colleague, and I’ve always felt gratitude for having had the chance to work so closely with Jason over so many years.

JC:

Thanks, Jeff. It was a pleasure, throughout, to work with you and all of our great contributors, too!

OB:

Are there any writers you discovered through this project? What, if anything, surprised you about the writers whose work you came to through this book?

JC:

I’m not sure we discovered new writers rather than new avenues of research in writers we may already have been following. When we first heard presentations and received draft chapters from Emily Kopely on Virginia Woolf’s library, Andrew Stauffer on his book traces project, Sherrin Frances on radical protest libraries, and Cameron Anstee on a bookstore/library collection like jwcurry’s Room 302 Books, to name just a few, we were extremely excited by the new directions our contributors were taking in their research surrounding the nature and uses of libraries. We were surprised by how many directions of inquiry resulted from the prompt of our call for papers. In short, all of the ideas we read in the chapters as they first came in were delightfully surprising and inspiring.

OB:

How do you view the role of an editor in relation to an anthology?

JAW:

An editor’s job is a balancing act: they need to help contributors achieve their intended voice while also ensuring that every contribution to the book is of the same calibre. In this particular case, I didn’t find that that was a difficult balancing act. When I worked as a the co-Managing Editor for The Bull Calf: Reviews of Fiction, Poetry, and Literary Criticism (2011-2019), the quality of submissions ranged dramatically; I remember sending one review back seven times for revisions. But when it came to Unpacking the Personal Library, I honestly felt that, from the beginning, our contributors were professional, scholarly, and readable. That made my and Jason’s job much, much easier than it might have been.

JC:

Agreed! Our role as editors was, throughout, to work help guide the work of our contributors through conceptual prompts that would give synthetic shape to our collaborative inquiry as a collection. Even with the diverse range of periods, materials and methods explored in this book, I think it reads as a very coherent collection and argument about the importance of libraries as objects of study, and as ever-slippery and fluid entities that individuals and institutions have consistently tried to fix and hold in place. It was a privilege to have exchanges with our contributors about their chapters in relation to this broader vision of the collection.

OB:

How did you approach incorporating your own work in the overall project?

JAW:

Jason and I had agreed to split our contributions to the book rather than co-author anything together. I took the conclusion, which was originally intended to be a readable, but still scholarly, reflection on the book’s key ideas: archives, the individual and cultural meaning of book collecting, and so on. But by the time I sat down to write that chapter, it was March 2020, and I had no access to any public libraries, which I needed in order to write what I’d intended to write. Naturally, this changed the tone and focus of the conclusion: it became a very personal reflection on book collecting and on Unpacking the Personal Library, which gave me space to think about my own books and what it means to collect, especially in the era of COVID-19 when libraries are closed. That aspect of the conclusion did, I think, (entirely unintentionally) make the book much more topical, because it gave me something concrete and very present to address; I think readers will really like that aspect of the conclusion and how it connects to the other chapters, which were written long before COVID.

JC:

The opportunity to write the introduction to this collection allowed me to explore a broad range of questions about libraries in history (I focused mainly in their recent history, from the eighteenth-century to the present). As I read through the rich historical literature and case studies about specific libraries of authors or institutions, I came to feel a tangible desire in these scholars of libraries to hold their often piebald and cryptic objects of study in a coherently discernible space and time, and I came to understand just how beautifully messy and fluid the library as a cultural assemblage has always been.

____________________________________________________

Jason Camlot is Professor of English and Research Chair in Literature and Sound Studies at Concordia University. Recent books include Phonopoetics (Stanford, 2019), CanLit Across Media (MQUP, 2019) and Vlarf (MQUP 2021). He is director of the SSHRC-funded SpokenWeb research partnership that focuses on literary audio collections.

J.A. Weingarten is a Professor in the School of Language and Liberal Studies at Fanshawe College. He is also the author of Sharing the Past (UTP, 2019), as well as more than three dozen articles, book reviews, and papers on Canadian arts and culture.