On Anabiosis and Mosses Helping with Sleep

Submitted by Angélique Lalonde

On Wednesday, on the way to the river, I stopped in my tracks, struck by the moss habitat on a birch tree on the bank. It is a twinned paper birch — with one dead trunk snapped off about two meters above my head, and one live trunk reaching another six or eight meters beyond that. I crouched down, drawn into the variegations of green, soaked wet with rain and lit brightly by sunlight emerging from behind the clouds for the first time in weeks. My eyes were drawn towards the intertwined complexity of the moss habitat I found there. I inhaled deeply, spontaneously, then thought of Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book Gathering Moss, that I currently have on my night table because it helps me sleep to read about mosses when I am trying to settle between wakefulness and dream. Unlike Kimmerer, I do not know how to name the mosses I am looking at, but I thought of her descriptions of variegated moss communities and counted at least five different moss varieties in one small area of the trunks, down low near the ground. And then the closer I looked I could see greater variety of lichens intergrowing with the mosses.

I wished I had a hand lens with me to peer deeper into those worlds, as Kimmerer does. I didn’t, but I spent time looking with the capacity of my own eyes, and when I emerged, the world had readjusted, shifted somehow.

I had been stuck in my head all morning with the news of being longlisted for the Giller Prize. The busy string of texts, emails and phone calls from friends, agent, publicist and publisher, and other writers I know, most of whom had heard the news before I had because I had not yet tuned into the world outside my home when the announcement was made! So my morning was buzzy. Buzzy in an elated sort of way, but buzzy. A readjusted reality I did not know how to relate to. After my partner left for work with the kids, who have blessedly returned to preschool and grade one, I was left alone with my dog and the virtual communications that I felt excited about, but that are so difficult to relate to in an embodied and connected way. I had work I wanted to do, like finishing my post for Open Book, and preparing for my book launch and second ever public reading at my local library that night. I needed to come back to earth and was having trouble not tuning into the internet world and the buzz of those kinds of relations.

So I went to the river. And encountered the mosses. And the mosses brought me back to the kind of being that makes sense to me, filling me with wonder and curiosity, the kind of feelings that are the kind of feelings I feel lifted by when I am able to write from them. There are other kinds of feelings I can work from too, like frustration, and anger and confusion, but those weren’t the kinds of feelings I wanted to work from for my post, or for my reading, so I was grateful to the mosses and to Kimmerer for inviting me into the world of mosses and reorienting my affective pathways to deeper breath and grounded presence.

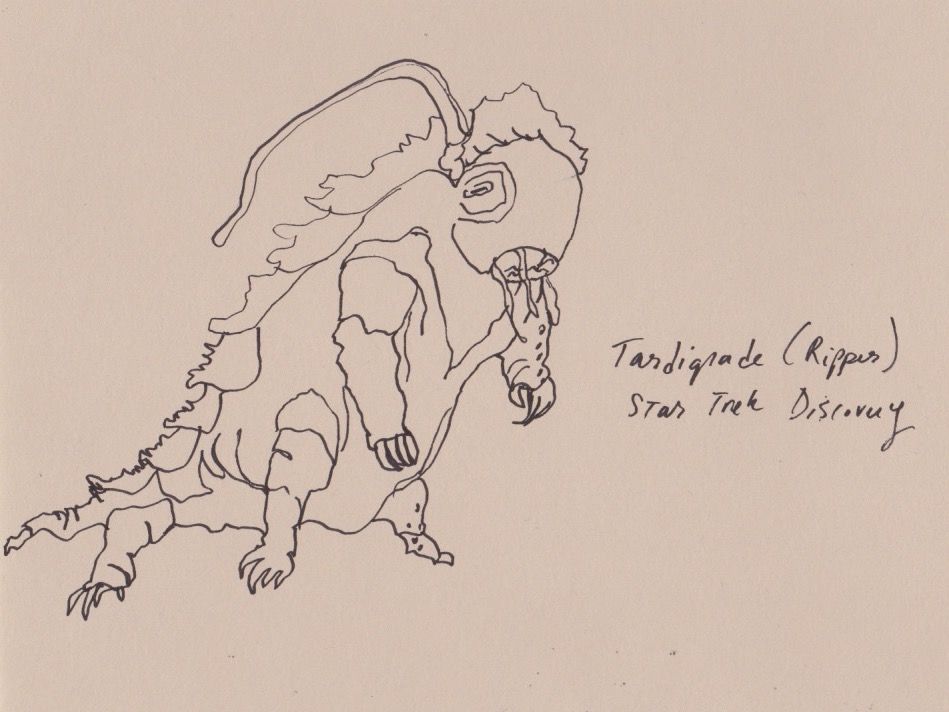

This kind of work is important to me right now because the last year has been a difficult year for me, as it has been for many people. I spent October-May struggling with debilitating insomnia that was unrelated to my children’s sleeping patterns as they are now, thankfully both sleeping through the night. Because of this I have had to reorient many of habits of being to find ways of calming my nervous system down enough to move between states of wakefulness and sleep. Things have improved drastically now, though I still find the transition a tentative one, approaching each night almost ritualistically, with the particular amalgam of reduced stimulation (no more Star Trek before bed!) herbs, and somatic practices that allow my body to calm and my mind to drift out of thinking into dream. I find reading Kimmerer’s writing about mosses deeply soothing.

I want to share a longer passage from Kimmerer’s book, one that I have stitched together into a shorter excerpt for brevity here because of the way she writes about the boundary between life and death played out in the world of mosses:

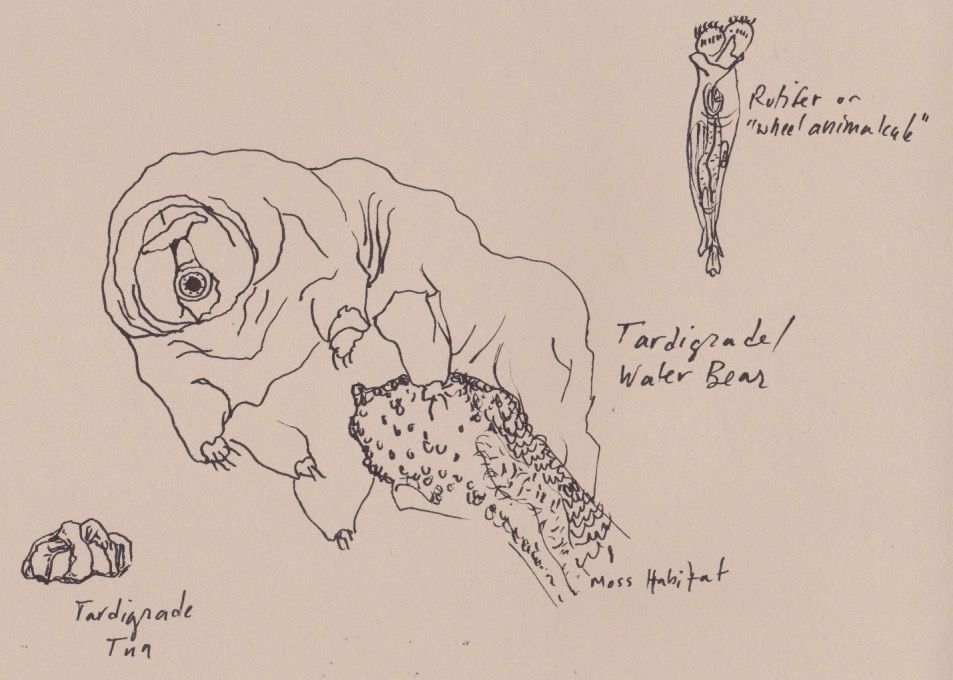

If I had to choose one animal whose life is most closely tied to the life of mosses, it would be the waterbear, or tardigrade…

As their name suggests, waterbears are reliant on the abundant moisture held in the interstitial spaces of a moss clump. They cross between plants on fragile bridges of water, spanning the capillary spaces in the moss… The moisture in a moss mat is as vital to the moss as it is to the waterbear. But, since mosses are nonvascular, their water content fluctuates with the amount of water in the environment. The moss leaves shrivel and contort as water evaporates, leaving them crisp and dry. The waterbears, too, simply shrink when desiccated to as little as one-eight of their size, forming barrel-shaped miniatures of themselves called tuns. Metabolism is reduced to near zero and the tun can survive in this state for years…

Rotifers, or “wheel animalcules” as they were first called, share this same remarkable ability to withstand drying. When moist, rotifers inhabit the water-filled spaces of a moss, like guppies in a multitude of tiny aquaria…

All three—mosses, waterbears, and rotifers—figured prominently in a nineteenth-century debate about revivification and the very nature of life. The behavior of these three blurs the distinction at the edge between life and death. All signs of life are extinguished when they are dry: no movement, no gas exchange, no metabolism. All enter a state known as anabiosis, or lack of life. And yet, as soon as water is returned, life suddenly is renewed…

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The process that allows these beings to hover at the boundary between life and death is still a profound mystery that is continually played out in the mosses beneath our feet.

— (from Robin Wall Kimmerer “In the Forest of the Waterbear,” in Gathering Mosses (Oregon State University Press, Corvallis OR, 2003), 59-60.)

I don’t know what it is like to hover at the boundary of life and death, but I do know what it is like to hover at the boundary between wakefulness and sleep, not being able to transition to a resting place when it is so sorely needed. I think a lot of us know what this is like. Whether it is hovering at the boundary between wakefulness and sleep or anxiety and groundedness, places where we feel ourself writing/creating/being/working/relating well, and places where we struggle with the anxiety of doing good work, wondering at the mystical interstitial space between.

I offer you these reflections on Kimmerer’s writing about mosses and the manifold creatures that inhabit them, as well as my own humble rapprochement to mosses on the way to the river because these are gifts that have brought me healing in these times of schism, modes of finding rest in transitional spaces, even under difficult conditions (and for those of you who are Star Trek fans, you may recognize the amazing tardigrade as the being who made possible to navigate the spore drive in Discovery, but that would take us to another place entirely!).

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Angélique Lalonde was the recipient of the 2019 Journey Prize, has been nominated for a National Magazine Award, and was awarded an Emerging Writer’s residency at the Banff Centre. Her work has been published in numerous journals and magazines. She holds a Ph.D. in Anthropology from the University of Victoria. Lalonde is the second-eldest of four daughters. She dwells on Gitxsan Territory in Northern British Columbia with her partner, two small children, and many non-human beings.