Cormac Mccarthy: "the Ugly Fact Is Books Are Made out of Books"

By Brian Panhuyzen

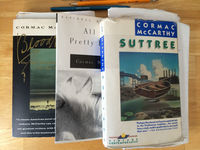

Before the publication and Oprahfication of The Road, and the Oscar success of No Country For Old Men, Cormac McCarthy was a critically-loved but relatively obscure novelist, unknown outside hardcore literary circles. He was also a recluse, having granted only one public interview, for the New York Times, in 1992. His first novel, The Orchard Keeper, he sent to Random House in 1965 (he says it was the only press he'd heard of), where it was read by editor Albert Erskine, William Faulkner's last editor. In a move that's unheard of in 21st century publishing, Erskine acquired the book on its quality alone, and though it barely sold, it began a 20-year relationship between author and editor that would lead to eventual success.

Like most of the writers who discovered McCarthy before The Road, the first novel I read (recommended by a friend, a recommendation I initially resisted because the Toronto Public Library catalogue labelled it a "western") was the 1985 novel Blood Meridian. This bloodiest of books, full of language of biblical verve, astonished and excited me in a way no book ever had before. The audacities of this novel are many: the heartstopping violence, the evisceration of punctuation, the cunning humour, the ringing absence of sentimentality, the opaque diction. To exemplify the latter, I have just drawn a copy from my bookshelves and discovered several sheets of scrap paper dense with jotted words and page references from probably my third or fourth reading of the book, words which for me were unknown, or used in a context with which I was unfamiliar. Here's a sampling:

- surbated

- parfleche

- gastine

- lobation

- ignis fatuus

- ristra

- tiswin

- pugmill

- shacto

- dunnage

- thaumaturge

- replevined

Typing this on my Mac, over half of these words are underlined as potential misspellings, meaning they do not exist in the stock dictionary. Note too that many of McCarthy's works are set in the southwest, and that Spanish and other languages may be incorporated into the text without textual clues, such as italicization. "Tiswin," for example, is a fermented beverage made by Apaches. I'm not sure it will fly on a Scrabble board.

One reviewer remarked on McCarthy's "stubborn refusal to bend his writing to the literary and intellectual demands of our era."

(I can't help but inert a personal thought here, that much to my own disservice, I've done the same with my own work. I've been counselled by some of the best in Canadian publishing, agents and editors, and am fairly confident I know precisely the kind of book I should write that would lead to something more than the aesthetic success I've enjoyed, but I have been unable to bring that kind of effort to something as grand as a novel.)

If anything, success of The Road is yet another testament to Oprah's power to popularize. Many McCarthy fans were astonished by the acclaim, and were also struck dumb with fear. Surely Cormac on Oprah was a sign of the apocalypse? Cormac at the Oscars meant the End of Days? (With McCarthy, thoughts of doomsday are never far.)

Many who might find The Road or No Country for Old Men too bleak should begin a tour of McCarthy with All the Pretty Horses, his 1992 National Book Award Winner and first volume of the Border Trilogy, and the novel that lifted McCarthy out of deeper obscurity. It contains a romance! One of the greatest criticisms of McCarthy's work is his vague treatment of women, but while it's true that they score low on the census count in his works, when they do appear there's nothing wrong with them. There are powerful matriarchs, or wise, mouthy whores (cringing a little here), or any range of strongly-rendered characters. It's true though that these are mostly stories of men, and as they are often historical and set outdoors, the action is centred around men engaged in jobs of killing or ranching or crafting of guns or wagons, so there may be less than the quantity necessary to satisfy women readers, though if I am to believe Canadian book marketers, McCarthy should not exist at all on the scene, and still be working in darkness, as men don't buy fiction, and women only want to read about women. (Funny that if you properly promote work, it can still sell regardless of how you arbitrarily define the market.)

They went up into the mountains a week later with the mozo and two of the vaqueros and after the vaqueros had turned in in their blankets he and Rawlins sat by the fire on the rim of the mesa drinking coffee. Rawlins took out his tobacco and John Grady took out his cigarettes and shook the pack at him. Rawlins put his tobacco back. Where'd you get the readyrolls? In La Vega. He nodded. He took a brand from the fire and lit the cigarette and John Grady leaned and lit his own. You say she goes to school in Mexico City? Yeah. How old is she? Seventeen. Rawlins nodded. What kind of school is it she goes to? I don't know. It's some kind of a prep school or somethin. Fancy sort of school. Yeah. Fancy sort of school. Rawlins smoked. Well, he said. She's a fancy sort of girl. No she aint. Rawlins was leaning against his propped saddle, sitting with his legs crossed sideways on to the fire. The sole of his right boot had come loose and he'd fastened it back with hogrings stapled through the welt. He looked at the cigarette. Well, he said. I've told you before but I dont recokn you'll listen now any more than you done then. Yeah. I know. I just figure you must enjoy cryin yourself to sleep at night. John Grady didnt answer. This one of course she probably dates guys got their own airplanes let alone cars. You're probably right. I'm glad to hear you say it. It dont help nothin though, does it? Rawlins sucked on the cigarette. They sat for a long time. Finally he pitched the stub of the cigarette into the fire. I'm goin to bed, he said. Yeah, said John Grady. I guess that's a good idea. The spread their soogans and he pulled off his boots and stood them beside him and stretched out on the blankets. The fire had burned to coals and he lay looking up at the stars in their places and the hot belt of matter than ran the chord of the dark vault overhead and he put his hands on the ground at either side of him and pressed them against the earth and in that coldly burning canopy of black he slowly turned dead center to the world, all of it taut and trembling and moving enormous and alive under his hands. What's her name? said Rawlins in the darkness. Alejandra. Her name is Alejandra.

My favourite McCarthy is the long, obscure novel Suttree, which is set in Knoxville, Tennessee in the 1950s. Some critics stupidly mistake the gravity of McCarthy's books with humourlessness, but nothing could be further from the truth. Suttree contains, along with moments of heartbreak and violence, some of the greatest comedy in literature. I'm tempted to lift examples, but I fear spoiling them for the reader. (Let's just say to look for the watermelons, and later, the floorbuffer.) Cornelius Suttree is a scholar from a well-to-do family who has abandoned everything to live among the squalor of Knoxville. His relationships with everyone — blacks, prostitutes, homosexuals, transexuals, indigents, aboriginals, criminals, cripples, and all manner of misfits — is so free of judgment and innuendo, it would be an insult to call the work "progressive." This is not an author paying lip service to cultural sensitivity — there is a very genuine sense that these are realistically the people of Knoxville. We are not insulated in any way from the prejudice they face at the hands of others, like the cops, but there's no feeling that any of this is offered gratuitously.

When he crossed the porch of Howard Clevenger's store on Front Street there was on old woman rummaging through a basket of kale there as if she had lost something in it. Oceanfrog Frazer was standing at the screendoor. He patted Suttree on the ribs. What's shakin, baby. Hey, said Suttree. They pushed through the door together. Atop the drink cooler squatted a black and ageless androgyne in fool's silks. A purple shirt with bloused sleeves, striped fuchsia trousers and matching homedyed tennis shoes. A gold leather motorcycle belt above a vespine waist. A hat from the hand of a coked milliner. Hi sweetie, he said. Hello John. Trippin Through the Dew, said Oceanfrog. Hey baby. Hey Frog, called a black from the rear of the store. What you want? Come here baby. I got to talk to you. I aint got time to mess with you. Suttree poked among the loaves of bread. Oceanfrog lifted a carton of milk from the cooler and opened it and drank. Hey Gatemouth. Yeah baby. You hear about B L's old lady catchin him? No man, what's happened? She come in over there Sunday caught him in bed with this old gal and started warpin him in the head with a shoe. The old gal raised straight up in bed buck naked and hollered at her, said: Lay it to him, honey, said: I was married to a son of a bitch just like him.

Like Blood Meridian, my copy includes a sheaf of papers with scrawled notes and diction (davited, catenary, lampion, withershins). For all its humour and hijinks, Suttree is also a profoundly sad book, and a haunting one at that. It is a book I never want to end. So I don't let it. It's always on the go. And if I do occasional reach the last page, it is without much manual effort that I find myself back on page one, starting again.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Dear friend now in the dusty clockless hours of the town when the streets lie black and steaming in the wake of the water trucks...

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book: Toronto.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Brian Panhuyzen is the author of the short-story collection The Death of The Moon (Cormorant, 1999) and a novel, The Sky Manifest (ECW, 2013). He has written for the Just for Laughs International Comedy Festival, worked as a typesetter and designer, and is a developer of databases. He lives in Toronto, Ontario.