Poetry School: Keeping it real with Wordsworth

By Deanna Young

Lyric poetry. We say it casually, but what does it mean? The musical connotation is there, even if we don’t accompany our lyric poems with music. An inherent music, then. The lifts and falls. Rhythm. Also, the swirling assonance, alliteration, and rhyme. Essentially, a short poem in which the poet or speaker expresses personal feelings.

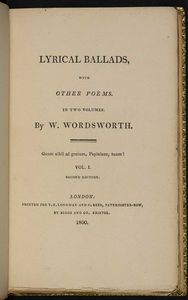

While William Wordsworth’s preface to the second edition (aka the 1800 edition) of his and Coleridge’s Lyrical Ballads has come to be seen as a manifesto of the Romantic movement, Wordsworth, of course, did not invent lyric poetry any more than he and other Romantic poets (Coleridge, Keats, Byron and Shelley et al.) invented romance. Eight centuries earlier, in Anglo-Saxon England, “Anonymous” had composed “Wulf and Eadwacer,” an enigmatic and terribly romantic lyric with a first-person, female speaker. “Wulf, my Wulf!” the poet calls out, “Hopes of you/ have made me sick, your seldom-comings.” And let us not forget Rumi in 13th-century Persia: “Where did the handsome beloved go?/ I wonder, where did that tall, shapely cypress tree go?”

It’s just that the lyric had not been in fashion in England for a century or so, having been muffled by the neoclassicism of Dryden and Pope. Thus Wordsworth, with his case for the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings recollected in tranquility, was just making emotion new again, if not immediately cool. As artists, we must never forget the fashion factor: that it is always at play, a limiting, emulsifying thing, and that it is our job to buck it—as in throw it off our backs.

Wordsworth’s “prefix”, then, is a “systematic defence” of his poetic theory, written at the urging of friends anxious for the success of the poems. He resisted writing it at first, partly because “to treat the subject with… clearness and coherence…it would be necessary to give a full account of the present state of the public taste in this country, and to determine how far this taste is healthy or depraved.” Fashion.

Oh, what the hell. But by deciding to pen the preface, he was forced to engage in a little trash talk:

“They who have been accustomed to the gaudiness and inane phraseology of many modern writers, if they persist in reading this book to its conclusion, will, no doubt, frequently have to struggle with feelings of strangeness and awkwardness: they will look round for poetry, and will be induced to inquire by what species of courtesy these attempts can be permitted to assume that title.”

How many of us has read a poem in a journal, for example, then looked “round for poetry”? Such disorientation is not new. Not to suggest that the unfamiliar is bound to be superior to the familiar. I would like to be always mindful, however, of the influence that familiarity can exert upon taste.

In favour of the “plainer and more emphatic language” spoken by ordinary, hardworking humans, Wordsworth then calls out the poets “who think that they are conferring honour upon themselves and their art” by indulging “in arbitrary and capricious habits of expression, in order to furnish food for fickle tastes”:

“However exalted a notion we would wish to cherish of the character of a Poet, it is obvious, that while he describes and imitates passions, his employment is in some degree mechanical, compared with the freedom and power of real and substantial action and suffering.”

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

In other words, Get over yourselves, Poets. He wanted to keep it real.

He further disparages the “triviality and meanness” in the work of some of his contemporaries, along with the “false refinement or arbitrary innovation.” And so the battle lines of poetry were and continue to be drawn and redrawn.

There is an urgency to Wordsworth’s preface, and he explains why. It is due to “a multitude of causes, unknown to former times, [and] now acting with a combined force to blunt the discriminating powers of the mind.” Was he talking about Instagram? Twitter? PS4? No. He means urbanization and mass media (newspapers): “the increasing accumulation of men in cities, where the uniformity of their occupations produces a craving for extraordinary incident, which the rapid communication of intelligence hourly gratifies.” Back to basics, he was basically chanting. “Poetry is the image of man in nature.” Period. And as for sublime nature, he saw no reason to trick it out with artifice.

Feelings first! (I paraphrase.) And let us not be taken in by “frantic novels, sickly and stupid German Tragedies, and deluges of idle and extravagant stories in verse,” not to mention “the magnitude of general evil” in general. I’m sure that when I first read this as an undergraduate, I did not fully appreciate its richness. The Real Housewives of Vancouver, is what I’m thinking now. Dr. Pimple Popper.

As for style, he rejects the personification of abstract ideas (I admit to having recently personified Light and Dark in a poem, though certainly not Truth and Beauty). He wants to “keep the Reader in the company of flesh and blood” (I am interested in flesh and blood). And no “poetic diction”, thank you very much (here with him I mainly would agree). Too prosey! he anticipates his critics objecting. How is that line any different from prose?! We might as well be sitting in a poetry workshop in 2019.

And furthermore: “The Poet writes under one restriction only, namely, the necessity of giving immediate pleasure to a human Being possessed of that information which may be expected from him, not as a lawyer, a physician, a mariner, an astronomer, or a natural philosopher, but as a Man [i.e., human being].”

By this I believe he means, Please don’t make me Google every other word.

There is much more, which I will let you discover for yourself. In the end, Wordsworth’s main campaign slogan has to do with the responsibility of the Poet to give pleasure to the Reader. He uses the words “please” (as a verb) and “pleasure” almost forty times here! In this respect, he comes across as someone whom it might be nice to date. Maybe the conversation wouldn't be all about him.

At the start of the preface, Wordsworth expresses his belief that the class of poems in Lyrical Ballads just might be “well adapted to interest mankind permanently.” We’re now at two hundred-plus and counting.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Deanna Young’s previous books include House Dreams, nominated for the Trillium Book Award for Poetry, the Ottawa Book Award, the Archibald Lampman Award and the ReLit Award, and Drunkard’s Path. Young grew up in southwestern Ontario during the 1970s and ’80s. Reunion, her fourth collection, belongs to that place and time. She now lives in Ottawa, where she works as an editor and teaches poetry privately.