Notes on My Futile Attempts to Evade the Creeping Tendrils of Inescapable Progress

By Jessica Westhead

The other day, my six-year-old daughter told me that I’m on my phone too much.

This was right after I’d grinned at a parking attendant and told him how thrilled I was to see a person at the gate instead of a machine. He smiled back, then sighed, “Yes, but the big companies like the machines better.” And I nodded grimly and drove away and proceeded to tell my daughter that this was one of the reasons why Mommy doesn’t like computers—because they take people’s jobs away. Computers can be very helpful, I went on, but there are some bad things about them too. “We all need a balance,” I said sagely, and then my daughter replied, “Mommy, why do you say I can’t be on screens a lot but you’re on your phone all the time?”

And even in that moment, as we inched along Bloor Street and the cold, slimy guilt oozed all over me, my fingers were twitching to dance across that cool, smooth glass and enter the unlock code so I could see what there was to see.

So many of us—including most of the writers I know—have an uneasy relationship with technology. We love the connection, the simplifying shortcuts, and the easy access to information it offers, but we hate the way it sucks away our time and fractures our attention. We try to trick ourselves into not using it so we can steal some of our concentration back. But whether we like it or not, social media is now an indispensable self-promotion tool for authors, and being at least somewhat tech-savvy is now an essential skill for basically everyone. The key is finding that balance, which (for me, anyway) is becoming harder and harder to achieve.

In any case, I’m grateful for that wake-up call from my frighteningly astute child because she’s a big part of the reason why I (try to) resist the siren song of technology at every turn. So far, her dad and I have mostly kept her away from apps and video games (preferring to let her watch way too much TV instead), intent on “front-loading” her with empathy and social skills and patience and a flourishing imagination and the ability to focus and to tolerate (and maybe even welcome?) boredom. In other words, all of the qualities that the apps and video games and the smartphone we will inevitably give her someday have the potential to erode. But I know that I can’t hold back the technological tide forever.

My tech-loving husband said to me recently, “Your war on technology must end.” Because I was moaning about a number of tech-related learning curves ahead of me, including the steps involved in uploading these very blog posts. And because every chance I get (especially after I’ve had a few drinks), I will blab endlessly about the dangers of devices with anyone who will listen. And because my anxiety is magnified when parents of tweens and teenagers complain that they’ve lost their children to Instagram (or Snapchat or Fortnite, or whatever). (I’m always heartened whenever I give workshops at high schools, though, and most of the young writers tell me they still prefer to write their first drafts with old-fashioned paper and pen. Yesss!)

I realize that I’m stubbornly mired in the past, and that my own fear of change is possibly interfering with my ability to see all the shiny, exciting future possibilities that technology will bring us. My circumstances also allow me to avoid the digital world, at least to some extent, if I want to. It’s important to acknowledge the benefits of rehabilitative and assistive technology, which improve the lives of so many people, as well as online innovations that help to protect and create safe spaces for vulnerable individuals, and to amplify marginalized voices. Reducing the use of paper saves trees. (I do dearly love actual books, though, and actual bookstores.) And of course labour-saving machines are useful. But labour-replacing machines are trickier. I was so happy to see that parking attendant because I couldn’t remember the last time I’d seen a human being doing that job. I prefer human beings because we can communicate and maybe even exchange pleasantries and thereby acknowledge we’re all sharing the same planet so why not be nice to each other? I hate dealing with machines because if something goes wrong, they’re useless. I have always scorned self-checkouts and online shopping for this reason, but I’ve become increasingly aware that they’re rapidly becoming the only options available. Or else there might be a single, exhausted teller or cashier or server behind the counter, nervously facing the long, impatient line of fuddy-duddies like me. Also, humans need jobs more than machines do.

It’s the relentless skulking of technology into all aspects of our lives, and especially our children’s lives, and our hopeless (or enthusiastic) acceptance of it, that upsets me the most. To the point that, every time I see a baby with an iPad, I want to smash it (the iPad, not the baby) on the ground and scream at the parents (and the companies that make the apps and then convince parents that they’re “educational”), “Do you realize that you are literally rewiring your infant’s brain right now?” I feel a similar sense of outrage when I see parents staring endlessly at their own phones when they’re with their kids. Because they might as well be saying, “This thing is more important than you are.”

I don’t want my daughter to see me on my phone all the time because of that, and because I want to model the alternative for her.

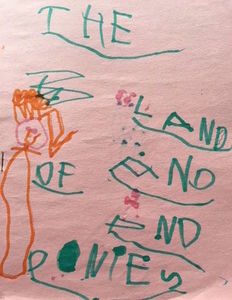

Last fall, when I launched Things Not to Do in Toronto at the wonderful Queen Books, my daughter had just turned five and was my guest of honour. To make the event a bit more fun for her, we invited a few of her friends to the party as well. While the adult guests mingled at the front of the store, we kept the kids busy at the back with snacks and juice boxes and a bunch of markers to write and draw in little blank books I’d stapled together. When I gave my thank-you speech, my husband brought our daughter up close so she could hear her name in the acknowledgements, and then he ushered her back to the kids’ zone so she wouldn’t be bored to tears by my reading. She seemed to think it was neat and all, but I didn’t think it made much of an impression on her until my second, smaller launch in my hometown. As I was getting ready to do my spiel, my daughter asked me if she could do a reading too. So we climbed onto the little makeshift staircase stage together and I introduced her, and she “read” from one of her own homemade books (which were displayed along with mine on the book table, tended to by the delightful Blue Heron Books crew). Her story was about a baby and a unicorn, and it was awesome.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I love reading to our kid, and I can’t wait until she learns to read and begins to discover books on her own as well. I love watching her trying out new words in conversation (and observing their effect on us), and taking risks with language and spelling as she learns to print. Her senior kindergarten teacher wisely cautioned us to stifle the urge to correct her spelling at this early stage, and that makes a lot of sense. Give her time to play before the inner critic is allowed to take over. (This is instructive for fully grown writers as well, because you can’t revise anything if you don’t get something down first.) To be clear: I don’t care if she wants to be a writer or not. I just want the gleeful, unselfconscious, gloriously single-minded absorption she experiences when drawing pictures or thinking up stories or doing anything creative to continue indefinitely. I want her to have access to that imagination-powered joy for as long as possible, and I’m afraid that the insidious, snaking tendrils of Too Much Technology will choke the life out of it.

I don’t want my daughter to see me on my phone all the time because I want her to know that a lo-fi, analog, tangible existence is possible, if only in bright, sweet, sepia-toned bursts.

But maybe I’m blowing this all out of proportion. Maybe I’m living in an archaic fantasy land. Maybe writing code will bring her joy. That would be pretty cool, actually. I should probably stop worrying so much, because worrying is useless and change is inevitable and my Luddite ways aren’t sustainable, and at some point I really should figure out how to use the GPS on my phone instead of printing out directions to where I’m going ahead of time.

There are some bad things about computers, but they can be very helpful too. And we all need a balance, right?

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Jessica Westhead's short stories have appeared in major literary magazines including Hazlitt, Five Dials, Room, Maisonneuve, Matrix, Geist, The New Quarterly, and Indiana Review. Her fiction has been shortlisted for the CBC Literary Awards, selected for a Journey Prize anthology, and nominated for a National Magazine Award. Her chapbook Those Girls was published by Greenboathouse Books in 2006. Her novel Pulpy & Midge, published by Coach House Books in 2007, was nominated for a ReLit Award. Her critically acclaimed short story collection And Also Sharks, published by Cormorant Books in 2011, was a Globe and Mail Top 100 Book, a nominee for the CBC Bookie Awards and a ReLit Award, one of Kobo's Best Ebooks of 2011, and a finalist for the Danuta Gleed Short Fiction Prize. CBC Books has called her one of the "10 Canadian women writers you need to read now." Jessica lives in Toronto with her husband and daughter.