Inside Reading Gaol

By Kate Sutherland

I spent yesterday afternoon in Reading Gaol. If you’re thinking, “The Ballad of,” you’re on the right track. It was an exhibition titled “Inside: Artists and Writers in Reading Prison,” and as the most famous former inmate, Oscar Wilde was front and centre.

A law and literature project that I’ve been working on for several years now is a book about lawsuits involving writers as litigants and/or literary texts as evidence, and one of the chapters is devoted to the trials of Oscar Wilde. The Wilde chapter is a bit of an outlier in the book in that the rest have to do with lawsuits directly connected to the working lives of the writers involved (contractual disputes, allegations of copyright infringement, defamation suits), whereas it was a criminal prosecution for personal conduct that landed Wilde in Reading Goal. But his legal troubles began with a defamation suit in which his literary writings were used as evidence against him, and that trial led to the subsequent criminal prosecutions that concluded with his conviction for “acts of gross indecency with other male persons.” Wilde was sentenced to two years’ imprisonment with hard labour which he served from 1895-97.

Reading Gaol, later known as HM Prison Reading, continued in use as a prison until November 2013. This exhibition marks the first time it has been open to the public so it was a rare opportunity to see inside. As noted in the exhibition guide, “the prison itself is the first exhibit.” It appears to have changed little from its Victorian origins, with three long three-story blocks of narrow cells stretching out from a central atrium to form a cross. (The primary change perhaps is that the single cells designed to isolate prisoners from one another were latterly used to house two or three young offenders each.)

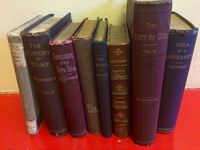

Visitors to the exhibition can wander in and out of many of the cells, including C.2.2 to which Wilde had been confined (he was admitted as Prisoner C.3.3, a number not a name, but later reorganization led to a change in the cell numbers). The paltry selection of books that Wilde was allowed during his second year of incarceration are on display (during his first year, he had access to almost no reading material apart from the Bible). And so are official photographs of many of the prisoners whose names are not known to us who served time alongside him. For the duration of the exhibition, each Sunday live readings of Wilde’s De Profundus, the 100-page letter he wrote from his cell, are performed by such luminaries as Ralph Fiennes, Patti Smith, and Colm Tóibín.

But the exhibition stretches beyond the prison itself and Wilde’s experience of imprisonment and the art he created during and afterward. It includes works of art (paintings, sculpture, photographs, videos, poems, and letters) displayed in individual cells, by a number of visual artists and writers.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Witnessing this historic prison serve simultaneously as an exhibit and as an exhibition space for artworks exploring the isolation, the separation, the brutality of imprisonment was overwhelming. If you get the chance, go! But, if not, you can still see and hear some of it here: https://www.artangel.org.uk/project/inside/

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Kate Sutherland was born in Scotland, grew up in Saskatchewan, and now lives in Toronto, where she is a professor at Osgoode Hall Law School. She is the author of two collections of short stories: Summer Reading (winner of a Saskatchewan Book Award for Best First Book) and All In Together Girls. How to Draw a Rhinoceros is Sutherland’s first collection of poems.

You can reach Kate throughout the month of October at writer@open-book.ca.