Q&A with Paul Vermeersch

By Ken Murray

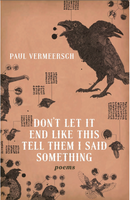

Paul Vermeersch is the author of five collections of poetry, most recently Don’t Let It End Like This Them I Said Something (ECW Press, 2014). He is also a visual artist and the Senior Editor at Wolsak & Wynn Publishers. For more information, go to paulvermeersch.ca

KM: In your art and poetry, you combine images from contemporary pop to ancient history with what feel at times like personal memories. In poetry, I’m thinking of several pieces from your recent collection, Don’t Let It End Like This Tell Them I Said Something. At the core of these collages, there is a punk rock ethos: work with whatever you have at hand, and make it your own. Does this sound right to you? Can you elaborate on how you approach your work, and what boundaries, if any, you set for your material?

PV: My approach to writing has changed a lot over the last twenty years. I think my process – if I have one, and I’m not sure that I do – is an extension of my attention span. Lots of things compete for my attention. Popular culture and ancient history are both part of the world. The subjects and images that end up in my poems and drawings are things that fascinate me. One day it could be cave paintings, and another day it could be cryptozoology. My mind wanders from one thing to another, and the poems get written along the way. The only boundaries seem to be my enthusiasms. Some are more philosophical, and some are downright kitschy – more TLC than PBS, I suppose – but I believe it’s my job to render my enthusiasms in a way that makes them interesting to other people. Whether or not I’m successful is up to them.

I don’t know if that’s exactly punk. Punk’s roots in America were part of a wave of radical self-expression, a reaction against the social conformity of the 1950s and 60s, particularly its manifestation in fashion and music. The British iteration of punk addressed entrenched class issues that didn’t exist the same way in North America, but both were reactions against the establishment’s notion of respectability. It is essentially an aesthetic of personal rebellion – a primal scream directed at men in suits and women in pearls... or tiaras. It relied on its capacity to shock, and I don’t see my work as being explicitly rebellious or shocking in the way that punk strove to be. I agree with the general aims of punk, but I’m not convinced that personal rebellion is an effective catalyst for change anymore.

Perhaps that sense of rebellion could be an ingredient in a poem – though I think I’m more likely to use satire or subversion. Lately, my work has had more in common with Pop Art than punk music, though it could possibly be some hybrid of the two.

KM: I’ve seen you read for an audience a couple of times this year, once at Wolfe Island Literary Festival, and also at The Platform Reading Series. Both times I’ve noticed that you have a strong sense of audience and place. Without being overly self-conscious, you interact with your audience and the environment in which you are reading, whether it’s breaking up a set of poems with off-the-cuff humour, or taking a moment to notice the birds chirping overhead. Is this capacity to interact with an audience something natural for you, or did it develop over the years?

PV: I’m pretty comfortable being in front of a crowd. I’ve been doing readings for a long time, and when I was young, I did some theatre. I’m also a teacher, so I have some experience not only performing for a group of people, but also engaging with them. There’s no need for a fourth wall when you do a poetry reading. It’s a personal experience. It would be weird to go on stage to read from a book and pretend the audience isn’t there.

KM: Many times when pop culture references show up in literature or visual art it is with a sense of irony, sometimes overbearing, along the lines of “see this thing inserted here. It’s supposed to be a joke (or is it?)” I find this limiting, condescending even; an artist unwilling to commit, using irony as a form or smokescreen instead of device.

Your work does not suffer this way. For example, when I look at “Les Demoiselles de Mystery Machine” I sense sincere affection for both Picasso and Scooby Doo. They work together, and the effect is startling. You are at times at play in your work, but never vague or uncommitted. There are no cheap jokes. An affirming sincerity binds it all together. Do you agree with the way I read this?

PV: I do have sincere affection for both Picasso and Scooby Doo. The line between high and low culture is an arbitrary one, a line drawn by class distinctions and intellectual snobbery. But there’s also a reverse snobbery that privileges the popular over what we know as fine art, but it’s still snobbery. Picasso was a wonderful artist, but so was Friz Freleng. I try not to privilege one over the other.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The question of sincerity is another thing altogether. In certain circles sincerity just isn’t cool anymore. I’ve heard it said too often, “I like this artist’s work because he doesn’t take it seriously,” and I can’t imagine a worse reason to praise someone. I believe this comes from either a gross misreading of what the artist takes seriously, or the unfounded presumption that anything that is humorous or that references popular culture cannot be serious art. Still, it seems for some people that taking art seriously is the biggest offence an artist can commit. And I am guilty. I do take it seriously – poems, paintings, cartoons, pop songs, symphonies – all of it, and I get serious pleasure from it, as well.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book: Toronto.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Ken Murray lives in Prince Edward County, Ontario. He teaches creative writing at Haliburton School of the Arts and at the School of Continuing Studies at the University of Toronto. He is a volunteer broadcaster in community radio and dabbles in several sports. Eulogy is his first novel. For more information visit http://www.kenmurray.ca.