Taking Your Medicine in the Editing Room

By Kevin Hardcastle

In previous posts I’ve talked about the hard road to getting a book published, and even a bit about the effort that goes into just getting those first few stories done. I’ve talked about submitting writing and dealing with rejection, so I thought I’d take some time to discuss another real important thing to get used to, as you ready work for publication.

Getting a story or a book accepted for publication has always been the one happiest moment for me, and still is. When I see the work in print, it is also very satisfying, and humbling, but it is that initial period of knowing that somebody is willing to take a chance on my writing that really gives me a charge. But, I also know, after this first book and many stories, that the work you do between that acceptance and publication will determine a great deal about what kind of writer you are. Those hours in editing and revision will test your skills and shape your work, and you had better learn to love that grind more than a little.

Don't take it personally

My first substantive editing experience was an interesting case. The oldest story in my collection, called “To Have To Wait”, was written way back in 2009, and eventually published by The Malahat Review in 2011. However, I’d had a story come close with that journal a few years before. “To Have To wait” was sent to Malahat specifically, and I got their first “Tentative Acceptance,” meaning that they’d decided they’d let enough good but rough-around-the-edges work go over the last few years, and they figured they’d give some of it a shot so as not to risk losing promising work from new writers. But, it would all come down to whether or not I could rework the story with them into something fit to publish.

That kind of pressure was good to have in an early publication, but it turns out that the experience was not some kind of brutal gauntlet to be run. I ended up being situated with Julie Paul, an excellent writer and associate editor, and we saw things the same way, and put together a far better story. At this point, I think I also benefitted from being an author who was very, very hard on themselves, and this translated well to the revision process. This has served me pretty well throughout my career, the ability to tear yourself a new one in every line and in the overall piece, and trying to bury your ego and any sense of preciousness that you have with regard to the writing.

So, let’s talk about that. The fact that writing is such personal thing, and yet, it is something that you have to approach as if your own personal designs, and the personal value you place on material, is absolutely secondary to the story itself. I saw a great write-up in This Magazine by none other than Open Book’s fine editor, Grace O’Connell, on how her students have often brought up the idea that something is necessary to include or maintain in the work because it is real, or “it really happened.” The gist of that article, and my point here, is that it doesn’t matter if it happened, or if it’s real, because the reality of the story and what is on the page is an entirely different entity. It actually suffers from being beholden to your own “real” experiences or feelings. It is a skill that good writers all have, to be able to step away from the work, even that which deals in very, very personal things, and to be ruthless with the edits so that you can best serve the narrative and the demands of the story itself.

I had a great professor at Cardiff University, Leone Ross, who specialized in workshops about gender and race, and about sex and erotic fiction, and she tore people to shreds when they brought in obvious “real” stories. As hard as it sounds, she told everyone in that room that stories about abuse, or hardship, or unwanted pregnancy, or men fighting and coming of age, were not intrinsically interesting. “This shit has happened to everyone. EVERYONE,” she’d say (or some approximation of that, sorry Leone). “Why is your telling of it interesting enough that I should read it?” That rattled a lot of young writers in the room, as they are often still figuring out how to process these experiences from their lives, and tend to use them by default, and often with good reason. But she was right.*

(*more to come on this is a later post, about writing from actual real life.)

Luckily, I’d been handed my ass over that already, back in undergrad writing workshops at the University of Toronto. Especially in a third year writing course with the great poet and professor A.F. Moritz, who saw some promise in the writing, but pushed me very hard to drop the affectations and write a fully realized short story. At that point, I wrote entirely from real life. Emotional, sincere, ambitious pieces about things that mattered to me, or things that happened, and they were all terrible. Because the craft around them and the story itself was not the guiding power behind them. Moritz, and my own determination not to be marginalized by those better-educated prep school kids, made me want to find my voice the right way and write a short story that functioned as a real short story, and wasn’t just recognizable as one by form and intention.

When I did eventually write a few good stories, it was one of them that got me into that grad school in Wales. That story was actually based on real events, but it was a story passed down and retold and rewrote by my memory of it. In short, it was about an uncle of mine who was very drunk when bombs started falling on Liverpool one night, during World War II, and his sister came back to the house to drag him to the air-raid shelter. By the time she got him out of bed and to the shelter, it was full, and nobody would let them in. They ended up at another shelter across town, with just a little old lady and her dog, and, in the morning, when they went back to their neighbourhood, the main shelter and most of their neighbours had been shelled to pieces. Now, that is a story that damn near writes itself, but I think, other than the material, it was the fact that I actually got a lot of the details wrong (as my family would tell you), or rather that I just didn’t let it all be dictated by the exact details or what really happened beat by beat, factually. I made up all of the connective tissue between the events, and the events were made to fit the story, but the story still kept it’s heart, and that was the lesson I’d learned going into my writing MA. All of this seemed to allow me to hit the ground running when I got there.

Personal stories mean something to you, because they mean something to you. When a reader picks up your work, they don’t have that same wiring in their brains, and they don’t have a natural connection to the story. You have to make that happen with craft and skill, and try to imbue the work with emotion and feeling while still being able to step outside of it and see it as another reader might. That is a very difficult thing, but all the best writers can do it, and I’m inclined to believe it begins in your approach to the craft of writing, word by word, and the work you do in revising the material over and again.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Just that simple act of reading a sentence many, many times, and breaking down every choice therein, can get you that distance and remind you that you are building something, not just feeling or emoting. If a carpenter or bricklayer was building a house, he or she wouldn’t just stand there crying and thinking about all of the families who’ll have their Christmases and birthdays there, and first steps, and breakups, and who will live or die in there. They just build the thing to facilitate the lives that might go on in there, with great purpose and functionality. Sure, it’s not quite the same thing, but I believe that focus on craft has helped me write very personal stories without letting it all get in the way of the actual effectiveness of the writing, and the characters and narrative. Anyway, that is my take and I’ll try to expound on how I approach it in a nuts and bolts sort of way.

*

The red ink is a good thing

For those of you who are getting used to having people read and critique your work, you might have had the experience of getting a piece of writing back and seeing in just lit up red with comments from an instructor or other folks in your workshop. While some of these criticisms may not be expert or even accurate (from other peers probably), many of them, especially from a good instructor or editor, should be welcomed and seriously considered. When you see all that red ink, it is natural to panic a little and think that you are doomed as a writer. In my experience, the more red ink you see, the better it is.

This is because no instructor or editor or reader worth their salt is going to spend all of their time writing thoughtful or precise notes on where you might improve your work if it is actual garbage. In fact, the thing you should fear most is the few lines of "nice try" or "good setting" with very little positive or negative criticisms. If someone who knows what they are talking about has taken the initiative to write all of these down, even if they are surly about it, and to the point about significant faults in the work, it means that they think it is worth saving. They think that it is worth revising and reworking and that they can see a path to where the piece becomes a good bit of writing, or story, or book-length work. This still means that you'll have a lot to do to get there, and that you'll have to swallow your pride and really consider these criticisms, but it is actually a good thing to have pages marked up or paragraph after paragraph of notes at the end. Of course, you will gradually learn that some people are also awful at critiquing, but you start to see that as you become more comfortable shredding your own writing. Otherwise, if you see that something you think is fine turns out to be problematic or in need of revision, by a half-dozen capable readers, you have to take that seriously, even if you think it is great in your bones. Actually, hell, you should definitely take a cold hard look at it if you feel that way.

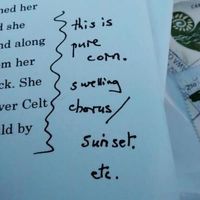

People have had a laugh at some of the photos I’ve put up on social media with notes from my editor, John Metcalf. He is known as a very tough editor, with a precise vision and philosophy of what good writing is. Well, I tend to see eye-to-eye with him on most things, and I think I’m not at all precious about the work, but even still, I get some corkers from my editor. Some writers have cringed just seeing them, and ask if it bothers me. It really doesn’t, as I know he is earnestly using his skillset and knowledge to make the work as good as it can possibly be:

The above images are parts of the edited manuscripts for some stories of mine, as they were used in a conversation with John Metcalf for The New Quarterly. In them, there are a few examples of where I used pushed the language a little too much and used “oft” a bunch of times. After awhile I’m pretty sure John was apoplectic from finding them. I said in that interview that I use a lot of antiquated words and strange conjunctions, but that a lot of it is by feel, and though my early lack of rudiments and later, years of limited access to working with other readers and peers, has often lead to interesting writing, it can also go sideways. John let me know here.

He also took a good rip at a line that could’ve been lifted from the crappiest thing that Cormac McCarthy ever threw in the trash. I knew when I wrote it that it was a stretch, but I still kept it in anyway. John called me on it, and it was cut. Rightfully so. Generally, because I have very specific opinions on the writing process, people think I might fight in the edits, but I also appreciate being told straight up when an experiment goes awry. Listening to your editor, even if it is a suggestion that is more significant and will lead to a ton of overhaul, is a good thing to get used to. For example…

This is an edit that people responded to hilariously, and that I’ve posted with another entry. It is a fair bit heavier than the other examples, in that it is John essentially telling me to scrap the end of the novel that I’m working on. And he is telling me to do so in no uncertain terms. Again, this is something that might give cause an author distress (I even got some messages about that kind of thing after posting it), but if something that significant really sticks in your editor’s craw, and you don’t have a rock-solid reason to argue, you should really be considering that advice. Again, I come to this confident enough that I think I could reject the ideas of a bad editor, and that comes from my being so hard on myself and working through so many edits over the years, learning how to spot them. But, John is a great editor, and even more importantly, a great editor for my kind of writing. So, while it has large implications on the novel, and the tone of the entire ending, this section is likely never to see the light of day.

It is funny that John invokes the idea of this coming across like the melodramatic ending of a movie. I’ve been open with the fact that I see almost all of my stories visually before writing them and that I am heavily influenced by observation and action over psychologies and asides from the characters. But, that melodramatic movie feel was exactly what I was going for here while I wrote this section. Emotionally searching for a way to sew this book up, and seeing it like the closing scene of some film I might have over-romanticized. For all of that I was missing the way this altered the tone of everything that came before, and did not suit the earlier chapters and how the book is written and where the story goes. This book, more so than almost any of my stories, will be truly built in the revisions to come. Knowing how to take my whuppings, and trusting what I’ve learned from years of taking them, is the reason I have very little doubt that we’ll be able to make it a very good novel after scrapping it out through the edits and revisions.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book: Toronto.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Kevin Hardcastle is a fiction writer from Simcoe County, Ontario. He studied writing at the University of Toronto and at Cardiff University. His work has been widely published in journals including The New Quarterly, The Malahat Review, Joyland, Shenandoah and The Walrus. Hardcastle was a finalist for the 2012 Journey Prize, and his short fiction has been anthologized in The Journey Prize Stories 24 & 26, Best Canadian Stories 15, and Internazionale.

Hardcastle’s debut short story collection, Debris, was published by Biblioasis in 2015. Debris won the 2016 Trillium Book Award, the 2016 ReLit Award for Short Fiction, was runner-up for the 2016 Danuta Gleed Literary Award, and was a finalist for the Kobo Emerging Writer Prize.

His novel, In the Cage, will be published by Biblioasis in Fall 2017.