On Research

By Leslie Shimotakahara

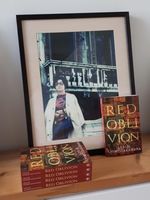

I can be nerdy, at times. I love exploring libraries and getting lost in the archives, as one might expect of someone who’s written two historical novels. My first novel, After the Bloom, focuses on the Japanese-American Internment during the Second World War, and my more recent novel, Red Oblivion, deals with the Chinese Cultural Revolution in the 1960s. In the case of researching both books, I immersed myself in reading an array of memoirs and history books, as well as other novels written about the same time periods.

Particularly fruitful for After the Bloom was my discovery of a book of photographs taken by Dorothea Lange of Japanese-American internment camps. Although Lange and other photographers, who worked for the War Relocation Authority, had been commissioned to take pictures that would document internees looking content and being treated humanely, the striking images she ended up capturing told just the opposite story and were confiscated by the US government. They didn’t see the light of day until several decades later, when they were published in a book called Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. A great source of inspiration, these photographs helped me to get inside my characters’ heads and bring to life various scenes.

It’s important to know when to stop researching and start writing. For any given historical topic, the body of scholarship out there is likely going to be vast and overwhelming. Even more so, when one includes online resources. Since it’s impossible — and probably not even desirable or useful — for a writer to cover in her reading the entire field, why even try? My own approach is to treat research as a supplement to my writing and imaginative process. I’ll read only until I feel inspired to write, in an ongoing back-and-forth alternation. A chunk of reading, followed by a chunk of writing. I don’t attempt to complete the entirety of my research before putting pen to paper, because that would be too daunting, and it could lead to undertaking months or even years of work that ends up not being useful. And there’s another pitfall of doing too much research, I believe: the author may have an impulse to include too much historical information, bogging down the novel. Sometimes, I find that at the revisions stage, I need to pare back my writing, by seeking briefer, more natural, elliptical ways to convey historical information.

Research can sometimes occur fortuitously, in unexpected places. What sparked my second novel, Red Oblivion, was the experience of living in my elderly father-in-law’s home in Hong Kong, during the final months of his life. Although his condo was located in an affluent part of the city, it was in a state of veritable disrepair. When my husband opened the door and we stepped inside, a humid fug, tinged with the scent of mildewy woodchips, greeted us. It turned out that all air-conditioners had long broken down, and it was summer when we arrived — thirty-five degrees and very humid. Having just received news of my father-in-law’s collapse and hospitalization, we’d caught a red-eye flight in from Toronto. Sepia stains formed strange continents across the living room ceiling, from a drainage problem on the rooftop terrace that he’d been too frugal to fix. One bathroom had been out of commission for years, and I was told that I risked electrocuting myself if I accidentally used it. I couldn’t help but notice an old, beat-up fridge in the master bedroom; it had long stopped working, but been repurposed as a filing cabinet because this eccentric man couldn’t bear to part with it. At that point, I knew a little about his life, which had been marked by multiple periods of hardship and resilience: during his youth, he’d lived through the brutal Japanese occupation of Hong Kong in the Second World War, and later he’d endured the Cultural Revolution in Guangzhou, China. All the signs of parsimony in his home were juxtaposed with the faded, decaying luxury of my late mother-in-law’s tastes: intricately carved, redwood furniture, lightly patterned wallpaper of an opalescent shimmer, now peeling at the edges. I’d never had the chance to meet her. Upon discovering some old albums full of pictures of her as a lovely young woman, I began to feel her ghostly presence all around me, at once haunting me and teasing at my imagination.

I started to keep a journal, simply with the intention of collecting details and impressions, which would perhaps be useful down the road. We’d be far too busy for me to commence a novel, I assumed. But during those long hours in hospital waiting rooms and at my father-in-law’s bedside, I brought my notebook along, just in case something occurred to me. For most of the time, he was asleep, and the doctors and nurses were communicating in Cantonese, unintelligible to me. Although I felt like there was something I should be doing to help, there was nothing I could do. I felt myself receding into myself, into a state of deep inwardness, and surprisingly quickly, this time around, I found myself in the midst of writing a novel.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Leslie Shimotakahara's memoir, The Reading List, won the Canada-Japan Literary Prize, and her fiction has been shortlisted for the KM Hunter Artist Award. She has written two critically acclaimed novels, After the Bloom and Red Oblivion, published by Dundurn Press. Red Oblivion, released last fall, was The Word On The Street’s Book of the Month for January, included in the 49th Shelf’s “Great Books for the Moment,” and praised in Kirkus Review for showing “virtuosity in this subtle deconstruction of one family’s tainted origins.” Leslie has a PhD in American Literature from Brown University. She and her husband live in the west end of Toronto.