Writing Within the Cracks

By Mark David Smith

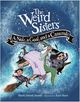

May is always a busy month for me. We have several May birthdays, summer to prepare for, and the usual sort of unexpected situations to deal with. Why, in this month alone, I have had to submit a first draft for a new Weird Sisters Detective Agency book, help my daughter prepare for her driver’s licence road test, help my other daughter purchase a car, complete the installation of a basement bathroom, pressure wash the winter mildew from the patio, and change the winter tires to all seasons on not one but two vehicles. All this while I mark three class sets of essays and review a book for a friend’s website. Now that I put it to paper, it seems outrageous. But, I tell myself, things will calm down in June.

Yeah, right.

The fact is, every season has its own urgencies, every month its own celebrations and responsibilities. They say a change is as good as a rest. I’m not convinced. I suspect this adage was coined by a factory manager.

If there was one positive in the world’s response to COVID-19, it was that we learned how little of our daily business was actually necessary. It became impossible to fill the time—everything was closed. Thank goodness we had Netflix, people said. (Can you imagine if this had happened 20 years ago? The Blockbusters would have been closed, too. Either that, or we would have had lengthy waits as each DVD was carefully sanitized by employees in biohazard suits before being returned to shelves.) Now, the world is eager to get back up to speed. But at what cost? My days are becoming a blur again.

I have often been guilty of a fantasy in which a sudden glut of time solves my creative productivity woes—in other words, time to write. I imagine many creatives with day jobs feel this way. If only we had more time, we might do that special thing on our hearts, that project that sits by us, whining like a dog at the dinner table hoping for something delicious. Does the dog whine because it is not fed? Of course it is fed. It’s just fed with something else.

My wife helps me stay grounded. She actually doesn’t care if I write or publish anything. It’s not that she is unsupportive. She just loves me as I am. So when I complain about limited time, she just throws it back on me: “Write or don’t write,” she’ll say. “Do what you want. Or don’t. But while you’re deciding, can you put away your laundry?”

Of course, she’s right. It’s taken me years, but I’ve finally stopped longing for that future Halcyon of free time, and instead try to use whatever cracks I can find in my schedule to write.

I wrote the bulk of my first children’s book, an historical fiction novel, in 2010, the same year my wife and I decided to build a house. We had sold our own home and were renting the upper floor of a house in the same neighbourhood so that we could easily check on progress. There were plans to check, meetings, trips to retailers of lighting and flooring, paint colours to choose, contingencies to address. (At one point we had to redesign the garage because the land had settled to a different elevation than the surveyor had indicated.) And of course we had three young children in school and activities, and our own sometimes overwhelming teaching positions. Yet somehow, amid all that frantic hustle and bustle, I managed to produce 86,000 words. How did I do it? Simple. Bit by bit.

I’ve been inspired—I won’t admit to being intimidated—by other writers who seem to have had a superhuman for prolificacy. C.S. Lewis, Oxford scholar and Christian apologist, wrote his seven Narnia books, his three science fiction novels, a novel for adults, many apologetical books, and works of scholarship, all while maintaining his teaching and tutoring schedule and, for many of those years, caring for the elderly Mrs. Moore, the mother of one of his deceased friends. It is said that he never once found more than fifteen minutes at a time for writing.

Fifteen minutes. What can you accomplish in fifteen minutes? Or rather, what must you?

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

A bit closer to home, I have twice had the pleasure of having dinner with Eric Walters when he and I both presented at a local school. I took the opportunity to ask how, as former teacher himself, he managed to start a writing career which currently spans more than 100 books. He told me that he said good night to his wife around nine o’clock, and while she slept he spent a few hours writing. (After we said goodbye in the parking lot, he informed me that he was returning to his hotel room for a “few hours of editing” for another book. He always has something on the go!) In other words, rather than complain about a lack of time, he made a choice about how he wanted to use the time he had.

In my own neighbourhood, my friend David Starr manages his role as principal of the largest high schools in the district while churning out novels for young people in multiple genres. He’s got a series of historical novels, hi-lo sports books, and even two non-fiction books to his credit. Like, Eric Walters, Dave sets his work aside—not easy as the one at whom every buck has to stop—and devotes a little time each evening to write. If anyone had an excuse for not writing, I’d say it was Dave. But he doesn’t complain. He writes.

What these writers have modelled for me is that I ought to find life an inspiration, not an imposition. To do that, I have to hold onto my thoughts, sometimes over many years, cultivating them slowly in order that they might bear fruit. And though it seems counterintuitive, it is a truth that the more I accept the limitations on my time, the more I can produce within that limited time.

Sometimes I even put the laundry away.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Mark David Smith is the author of The Deepest Dig and Caravaggio: Signed in Blood. A public school teacher, he lives in Port Coquitlam, British Columbia.