How I look at a map (part one)

By Matthew James Weigel

Art is all about process. Community spurs us on and the practice of creation is an active one. There is of course the cliché about art never being finished, merely abandoned, but in my opinion, neither of those concepts gets to the heart of it. To live a creative life, to be a poet, to make art, these are all active, verb-oriented ways of moving in the world. It is the people around you and the networks that you’re a part of that will sustain you in your career, in your life, and in your bones.

In the interest of supporting that, I would like to share with you the process in the construction of a new work. It’s going to be a visual piece based on maps of Edmonton. I’m going to be utilizing archival material, my computer, a tablet, and some art and design software. I’ll include links and descriptions of all of that at the bottom of the post, and I’ll talk a little bit about some free/low-cost alternatives as well.

Let’s get started: to the archive!

I’ll be using the City of Edmonton Archive’s map collection. I’ll start by browsing. I tend to start with old maps first, and work my way forward, it can be generative to get a sense of the way things change by looking at that change visually on a map. The early survey maps tend to be bold and ambitious in what the future city will look like. These visions for Edmonton tended to come with grand boulevards and a rigid grid of streets and avenues, neatly numbered in the cartographer’s confident hand. Later maps show how these visions gradually changed, were scaled back, or made real in ways larger than earlier planners could not have dreamed. What changes most is the loss of information about the land. Areas marked as stands of poplar are now blocked in as residential neighborhoods. Creeks shorten. Lakes shrink or disappear entirely.

I tend to look at the place I am now and try to better understand what it was. I try to understand what it might be. I live at the juncture of the old fort hill road, an ancient gentle-sloping trail to the river, and the canadian pacific railway tracks. It is a blessing to live in the place your ancestors have walked for countless generations. But it is also a responsibility to learn, to connect the dots, to share the stories and the knowledge. This spot has looked very different through the years:

Here is the 1882 survey, with Edmonton’s first Métis riverlots were marked out:

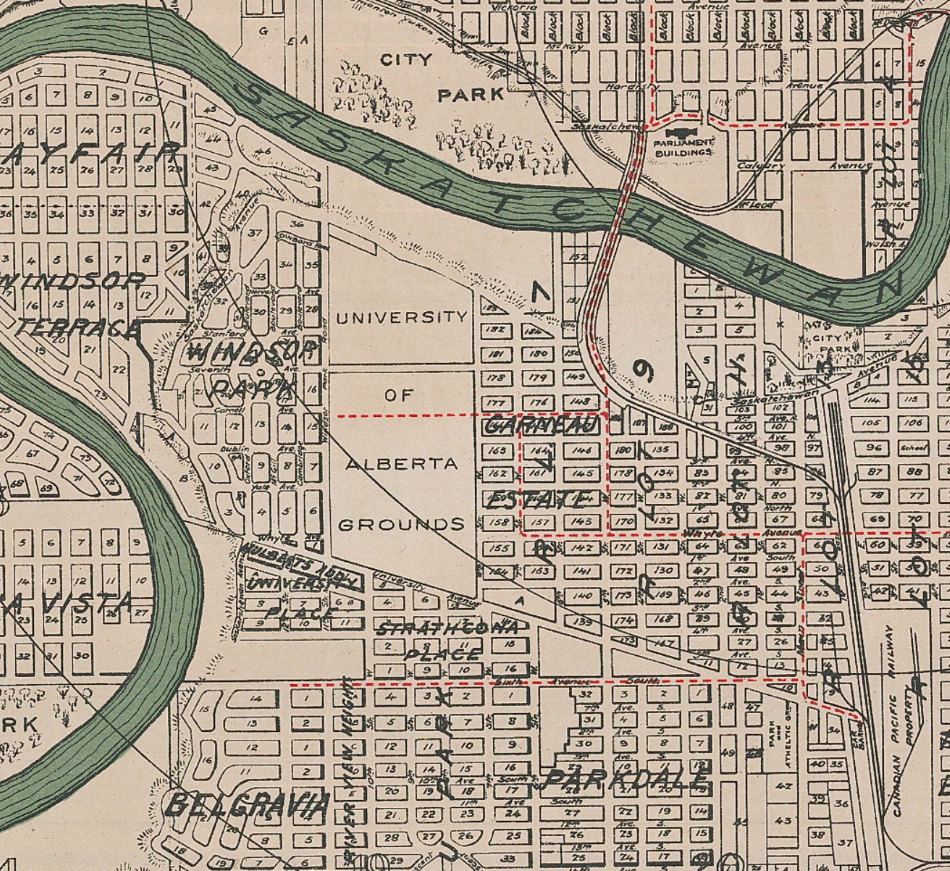

Here is a planning map from 1912, and within only a single generation you can see how the plans for the city had changed along with how the land is represented: flatter, and with parks:

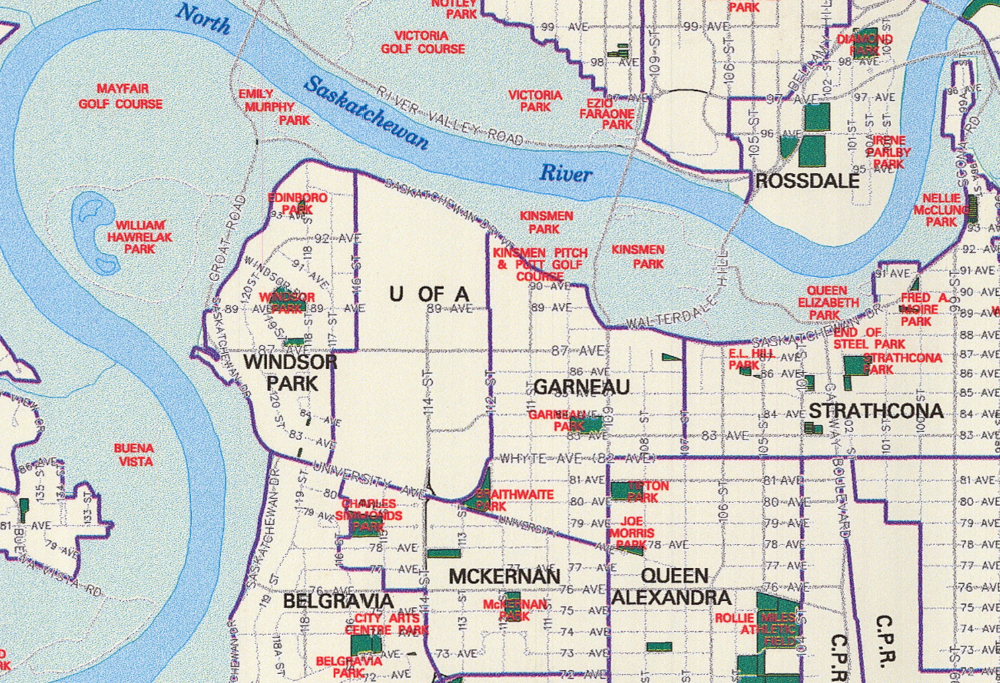

But then I found this:

“Named and Unnamed Parks”

What better way to track the spaces marked and unmarked, the lands possessed and dispossessed, than to follow the colours and outlines of this map. Nearly a century later and the city is decidedly different. Not only did some plans change, but who the city chooses to recognize in name tells many stories. The plan for a residential was quickly abandoned for the creation of the Royal Mayfair Golf Course: one of the largest private parcels of land leased from the city for a song. It is flanked by two small public parks. One named for a corrupt mayor whose questionable re-election sparked a riot. The other named for a fervent campaigner for eugenics and Alberta's Sterilization Act.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

But it’s those small slices of uniform green I’m most interested in for this piece. I’m interested in how they’re blocked in and enclosed by roads, over-written by names. I’m interested in how the unnamed parks are allowed or not allowed to take up space. And how big does a park have to be before it gets a name? Does it have to fill the box that’s made for it?

Lots of guiding questions! Thinking through how they might be answered is part of the process. I might look at some other maps and see what’s covered or re-covered. I might look at some of the planning documentation or even what the city’s website wants us to know about its parks. All of these can lead us to the words we’re looking to put on the page.

Stick around to find out where we're headed in part two!

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Matthew James Weigel is a Dene and Métis poet and artist. He is the designer for Moon Jelly House press and his words and art have been published in Arc, The Polyglot, and The Mamawi Project. Matthew is a National Magazine Award finalist, a Cécile E. Mactaggart Award winner, and winner of the 2020 Vallum Chapbook Award. His chapbook It Was Treaty / It Was Me is available now. Whitemud Walking is his debut collection.