Don't Write What You Know, Know What You Feel

By Wendy Orr

‘Write what you know,’ must be one of the most common and boring bits of writing advice. I’d say, ‘Don’t worry about what you know – just know what you feel.’

You can research most things you need for your novel’s locations, plot details or characters’ professions. You can watch live feeds of a town center or eagles’ eyrie; interview people with relevant experience, and since we’re talking about fiction, you can - you know – make stuff up. (I know it seems crazy, but I occasionally need that reminder: these people aren’t real – they’re actually all in my head, and I get to decide what they do.)

Of course you can google emotional reactions too, but you don’t need to. You know rage, and the nuances of guilt, shame and hurt; I hope you know love; infatuation; desire. You know how these emotions affect your body: the glow of adrenalin, the churning stomach of fear, the rash behind the knees when stress becomes chronic, the realization that you’ve actually pulled out a small patch of hair with anxiety. Yours may be different: everyone has their own things – individual, but rarely unique. And these are the things that a reader empathizes with.

Most of us will turn pages to find out what happens next, but to be truly drawn in to a book, we want to know what the protagonist is feeling and not just what they’re doing.

Four years after breaking my neck and various other bones, I used my own trauma in the YA novel Peeling the Onion. Astonishingly, I thought that making the protagonist a seventeen year-old girl instead of a thirty-seven year-old mother, occupational therapist and writer, meant that it wasn’t autobiographical. Of course it was.

Luckily we don’t need to go to those lengths for emotion. We’re writers – we extrapolate; we exaggerate; we chase thoughts to a myriad of conclusions.

Part way through writing Dragonfly Song, I realized I was plumbing not so much the grief of physical pain and incapacity, but the sense of exclusion that having a disability can bring. Peeling the Onion, for all its mirroring of my own emotions, hadn’t been cathartic to write. Dragonfly Song, its early drafts dredged straight up from the subconscious, definitely was.

Cuckoo’s Flight, once I’d finally realized that my protagonist’s joy in her horses was actually tempered with loss, drew on the more day to day drudgery of chronic pain and physical limitations.

On the surface, there doesn’t seem to be much in common between my life and my characters’. Like Dragonfly Song and Swallow’s Dance, the story is set in Bronze Age Crete. As well as the differences in our societies, I gave my young potter quite different injuries to my own – her broken pelvis means she’ll never be able to walk without pain and a crutch, whereas I can now walk unaided for several kilometers. (Treatment modalities have probably improved in the last 4000 years too.) Unlike her strong upper body, my unstable cervical vertebrae mean that I can’t sit in a car on a bumpy road without severe pain, and will certainly never drive a horse and chariot as she does.

But those details are minor. The emotions we share are what matters, and they’re not so different. Most of all, it was the shock of realizing that although I order my life around my limitations so that I don’t think of myself as disabled, life still throws up obstacles that force me to see the truth. And the terrible, often humiliating shock of seeing that even when we think we’re dealing with our own problems, other people may not see us in the same way. As I was writing, I kept remembering an incident I hadn’t thought of for years: a librarian who told me she’d been asked about me as a speaker for a festival. ‘I told them you couldn’t do it,’ she explained kindly, ‘because they had stairs in the building.’

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

My theory is that if a memory keeps niggling while I’m writing, it’s asking to be transformed into something relevant for the story. The original incident doesn’t need to bear any relationship to how I use it. I think this particular memory surfaced after the plot turn that I used it in – it simply helped me feel part of what my protagonist did in her own very different situation.

Sometimes in workshops I suggest that people take an incident in their own lives, pull it apart and explore how those bones could be used for a totally different story. Or simply examine an emotion in a wide variety of different metaphors and descriptions and see where it leads, whether for a work in progress or a story that might just be sparked from the exercise.

Most of us spend lots of time and energy in life suppressing emotions we’re ashamed of – but if we acknowledge them, at least we can harness them for our art.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

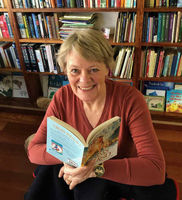

Award-winning author Wendy Orr was born in Edmonton, Alberta. The daughter of an Air Force pilot, she has since lived around the world, including several years in Colorado, in France, and England where she studied Occupational Therapy. After graduation, Wendy settled in Australia, but returns home yearly to visit her family. Wendy’s many books for children have been published in 27 countries and won awards around the world. Prominent among them is Nim’s Island, which was made into the 2008 film of the same name; a 2013 sequel, Return to Nim’s Island, was loosely based on Orr’s book Nim at Sea.