Why TV is Good for You

Submitted by Helen Walsh

If your mother was like my mother, you were told to turn off the television as a child (in my case, Family Ties or Miami Vice or Murder She Wrote or. . .) and pick up a book. Any book. Because everyone knew reading was better for you than staring at the idiot box.

Now, far be it from me to suggest my mother wasn’t right about everything. I realized about a week after leaving home for university that her life experiences of war, emigration, child-rearing and work gave my mother a very accurate read on people and situations. Despite my adolescent insistence I could take care of myself, thank you very much.

But like everything in life, television has something to teach us, especially about writing. That’s even more true now that the streaming services have pushed the envelope on excellence, including the many literary adaptations that populate the small screen.

The best of television stands its creative ground against film – that art form long considered its superior. And, I argue, many books, too.

I’ve previously written and produced film, but never TV. During the pandemic lockdowns, I took out subscriptions to several streamers – Amazon Prime, AppleTV, Disney+, BritBox, Sundance Channel; Netflix and Crave I already had. And boy did I binge.

The one I watched most was BritBox. A collaboration between the BBC and ITV, BritBox airs their own original productions as well as shows from UK terrestrial television (cozy mysteries, travel and cooking shows, endless historical narratives). The writing is almost uniformly good, and the production quality very high.

This summer, I wrote a pilot episode based on my second novel, tentatively titled Pull Back (at the prompting of a UK production company). At the same time, I was also revising the novel – an interesting cross-pollination. It provided the opportunity to deconstruct the story’s building blocks and then identify how to best tell it in each medium.

Fiction and scriptwriting have different strengths and weaknesses; exploring them simultaneously brought each into stark relief. This is what I learned:

- You need to establish the character voice and the tone right out the gate. In television that starts with the cold open/teaser segment which comes before the credits. In novels, that’s your very first sentence.

- The setting – or the world of the show – is critical in a visual medium like television. It’s so central to telling the story it’s another main character. I feel that sometimes setting is sacrificed in novels. Seen as less important than character, plot, or theme, many books don’t vividly weave in enough of the sights, smells and feels of their world so the reader gets immersed in all senses.

- The relationship between characters sheds as much light as anything you write about them directly.

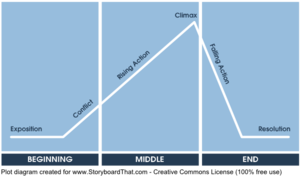

- Aristotle was right: the three-act structure is the perfect rhythm by which to tell a dramatic story. In television it’s five acts, but the same arc. Essentially, introduce the characters, the world and the problem right at the beginning. An inciting incident acts as catalyst for the story. Then an ascending escalation of problems/complications until it reaches crisis point, followed by a downward trajectory towards resolution.

- These ‘rules’ are broken all the time, but you should know them first and have a specific creative reason for jettisoning them. Readers/audiences intrinsically relate to this structure because it’s the basis for the majority of books, film, television and theatre they’ve watched all their lives.

- Most novels, regardless of genre or plot, needs to be suspenseful enough to draw the reader from one page to the next. I think that’s about structure; about designing an arc which leads the reader through unexpected turns, moments where all seems lost for the protagonist and moments where they win.

- Outlining or storyboarding is your friend. Especially if your narrative carries multiple plots (A, B and C storylines in scriptwriting), and/or time shifts. I outline every draft, and even to an extent individual chapters, but then let my imagination roam free. Structure gives me a goalpost, and its existence provides the security and freedom to head in whatever direction the story may take me. Whether that’s towards the goalpost or in an entirely different direction. The outline can always be revised.

- Conflict matters! As does suspense. Respect your readers enough to put the work into crafting the narrative.

I found it hugely instructive to read television scripts before watching a show, and then again afterward. Ideally, I’d locate different versions of the scripts (early draft, locked script, etc) and compare them.

The BBC Writers Room has many scripts available for free download; there are other sources online as well. (I’ve searched for a CBC equivalent and cannot find – if someone knows of one, please email!)

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

I sometimes reflect on what I was told as a child. What advice endures and what advice is outdated though the evolution of culture and communication. Television has transformed from when my mother warned me about it, into an art form as worthy as any other.

While books still provide, for me, the deepest and most thoughtful engagement as both writer and reader, the visual medium of film and television offers its own insights, provocation and entertainment. How lovely to have both.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Helen Walsh is the founder and president of Diaspora Dialogues, Canada’s premier literary mentoring organization. Formerly the publisher of the Literary Review of Canada and a founding director of Spur, a national festival of politics, arts, and ideas, Walsh spent five years working as a film/digital media producer in L.A. and New York. She lives in Toronto, Ontario.