Class, History, Fiction, and Form Part 1

By Geoffrey Morrison

It’s Monday, May 1st. If you’re reading this in Canada or the United States, you are most likely working today. I know I am. At this very moment I am probably guiding a group of adult learners through the English past perfect (or something) in my day job as a language teacher. There’s already a paradox; I just said I am teaching “at this very moment,” but I am also writing to you in the present tense, as though it’s my writing that’s happening right now. But it’s not my writing that’s now; it’s your reading. In fact, I’m not even writing this to you today. I am writing this six days ago. However, if I edit these words in the time between my now (six days ago) and your now (May 1st – or, god help us, maybe even later) – and, realistically, I probably will – then where will my now be, then? I don’t know.

If you’ve been itching to point out that I used “said” a few sentences ago when I should’ve used “wrote,” well, yes, me too, and so I am doing so now (or rather then). The difference between “write” and “say” is as much a problem for me as the difference between “then” and “now.” I don’t even know if there really is a difference.

All this to say (ha) that as your Open Book Writer in Residence for this month, I want to spend at least some of my time with you thinking about these very thorny questions as they apply to fiction. I mean time in a narrative. I mean speaking and writing. They have certainly been thorny for me, not least because I came to fiction after having first spent many years trying to write poetry, where time and writing and speaking seem to operate on quite different terms. But paradoxically (or not – maybe I was angling for these things to all link together the whole time), I think that I will not be able to explore these questions without also exploring the meaning of May 1st – this day on which, if you are in America or Canada, you are – like me – likely working. I wish we weren’t.

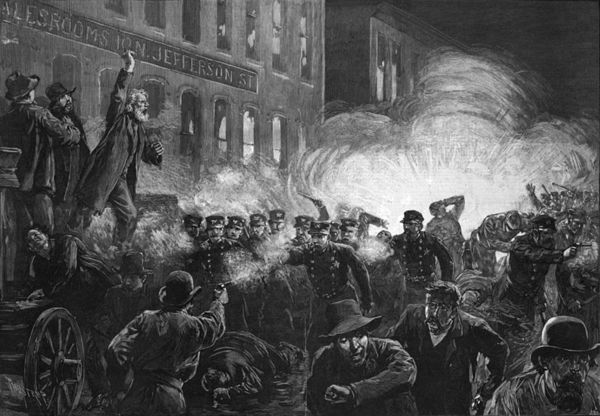

Today, May 1st, is International Workers’ Day. It will be celebrated by workers around the world with parades, rallies, red flags, and, crucially, paid time off. The United States and Canada, with their Labour Days on the first Monday of September, are conspicuous exceptions. I felt this gulf acutely when I was teaching an online English class to students logging in from across the globe. My students in China quite reasonably wanted to know if there would be classes on May 1st, as in their country it is a paid holiday. I don’t like not telling people the truth when I know it, and so I told my class that, in Canada and the United States, politicians and the more politically quiescent trade union leaders had been afraid of May 1st’s revolutionary associations ever since the street violence at Haymarket in 1886. So they picked a different day in September with no such significance. I told my students living in countries where the 1st was a holiday to please enjoy their day off and not come to class. And I expressed my regret that, due to a few fearful people a hundred years ago, I would not be able to join them.

As it happens, I cannot think about the problems of writing and speaking and time in fiction – and, ultimately, about form in fiction writ large – without also thinking about workers, social class, and fearful people a hundred years ago. Or two hundred. Or five hundred. Or more. They are all still governing the course of our lives from beyond the grave. We have a name for what it is to be governed by the fearful imaginings of the dead: we call it “history.” So really what I am saying (or writing, or whatever) is that my thorny problems of fiction and form are historical problems, too.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

Over the next few days, I am going to try to explore these historical thorns, these fearful ghosts. I will offer some ways we might reimagine the novel – supposed to be a “bourgeois form” – from the standpoint of those who believe that workers have a world to win. It won’t be easy, but I will do my best. As much as I will do so as a writer, I will also do so as a worker. I make my living as a teacher in a unionized workplace, a fact which gives me great pride and also a real sense of empowerment in comparison to other jobs I’ve had. But I am also a single individual whose knowledge and reading and life experiences are of necessity particular and incomplete. No one can do it alone. If, in my efforts, I manage to get you to think about these things as they apply to your own history, your own ghosts, then the person writing these words six days ago will be happy, later.

The views expressed in the Writer-in-Residence blogs are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

Geoffrey D. Morrison is the author of the poetry chapbook Blood-Brain Barrier (Frog Hollow Press, 2019) and co-author, with Matthew Tomkinson, of the experimental short fiction collection Archaic Torso of Gumby (Gordon Hill Press, 2020). He was a finalist in both the poetry and fiction categories of the 2020 Malahat Review Open Season Awards and a nominee for the 2020 Journey Prize. He lives on unceded Squamish, Musqueam, and Tsleil-Waututh territory (Vancouver). Falling Hour is his first novel.