An Interview With Phoebe Wang

By James Lindsay

“Like jarring a sore bone, you wince, and the poem gasps out of you...” - Phoebe Wang

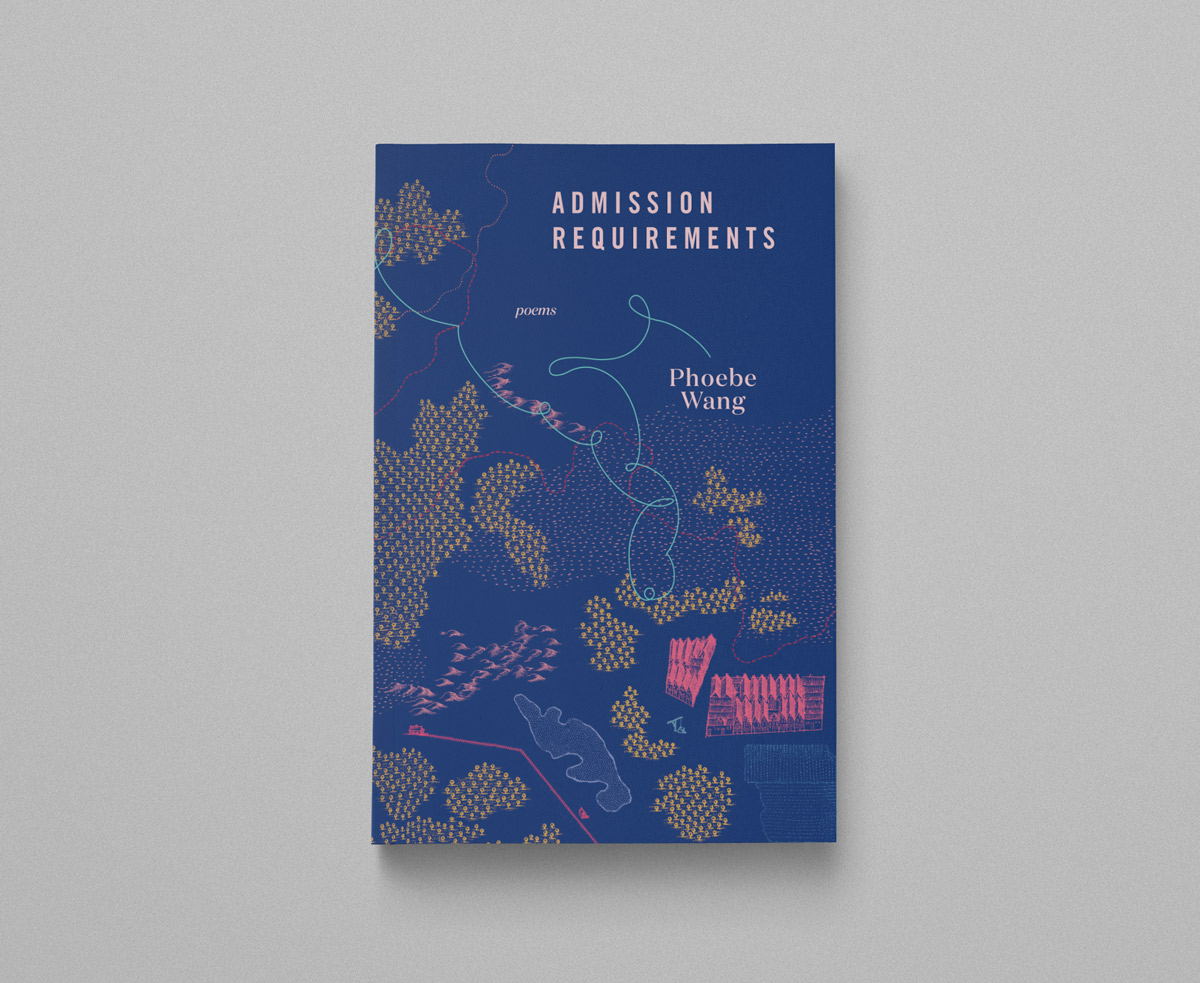

The geography of Phoebe Wang’s Admission Requirements feels like it’s always in a state of flux. The speaker is traveling with us, looking for home, but “home” becomes a question the further we go. Instead of home, maybe “place” would be more appropriate. But then Wang turns her eye to the plural of places and how they are divided, how to cross one to another. What we are left with is a doubtful map of different voices gently luring us into their stories.

James Lindsay:

Admission Requirements has a wide geography and cast of characters that span two distinct sections. How did you separate the poems into the two sections?

Phoebe Wang:

At first, I didn’t have any sections at all! But the long poem “Portage” seemed like it had a natural break before it, so I added a section break there. Then with “Yard Work” in the first section, my editor suggested adding another longish poem, which became “Sudden Departures” to balance out “Portage.” Loosely, the first section is preoccupied with different kinds of arrivals and entrances, and the second section with departures. Or in another sense, being admitted and then what has been admitted. This wasn’t deliberate, but it’s a very symmetrical book. It’s exactly 100 pages, with the section page coming in on page 49/50. So the two halves of the book are in a sense, reverse images of each other.

JL:

You and I spoke in person a little about the difficulty of approaching a second book. You said something I thought was very interesting, which was it felt like learning to write all over again. Could you expand on that?

PW:

I searched for a long time for what might be referred to as the ‘voice’ of Admission Requirements, rewriting the entire manuscript several times over 5 years. What I mean by ‘voice’ is a particular kind of opacity and irony, a musical tone that would both include the reader with direct language, yet play on the double meanings of well-worn phrases. That voice also included a specific relation to metaphor, to diction, to the line, and so on, that was directed by the contradictory subject matter of identity and place.

So now as I approach new subjects-- such as desire, dualities, and the staticness of the artist’s life—I feel as though I need to completely rethink how I approach the line and language. Different word choices, a different relationship altogether to imagery. This might seem extreme, even impossible, but I’m not trying to unlearn what I’ve already learn. Rather, to begin again at the point that my first collection brought me to, in order to depart further.

JL:

Perhaps this is an impossible question to answer, but where do you look for the voice? Does it come from within, or do you find it outside of yourself?

PW:

The boundary between the inner and the outer is porous as the body. The inner voice is shaped by outer, historical forces-- the weight of colonial policy that made English the language I so mostly think in, but it’s an English inflected by a particular lack, an English spoken and sung by my Chinese parents, mixed in with Cantonese vowels. So I look for the voice of a poem among the accents and intonations, the billboards and overheard expletives, the jams and lectures that seep through the ear and the body into the poetry making machine of the mind and the spirit. An image, a few phrases will arrive and sound true. I speak them slowly, because at times the poet is a ventriloquist, and the poem a foreign language. The voice of poetry is also at times an ineluctable wordlessness, like the impulse to sip a glass of ice water, a reflex. Like jarring a sore bone, you wince, and the poem gasps out of you.

Your CanLit News

Subscribe to Open Book’s newsletter to get local book events, literary content, writing tips, and more in your inbox

JL:

Does the voice change for you when you read aloud in public? Poetry in such a insular compositional process, part of the private inner life. So by making the voice public--does that change the poem for you?

PW:

For some reason, writing and putting the ephemeral into language already feels to me like an externalizing process. Reading aloud and projecting for an imagined audience is a part of how I compose. However, the voice of the poem does change when I’m confronted with a real, live audience. My tempo and volume and tone shifts with the response and the palpable energy of the audience. At the same time, I’ve been startled at how the voice of poem thickens, solidifies, becomes a kind of totality that is greater than its parts.

JL:

What are you working on at the moment? What can we expect to see in the near future?

PW:

I have begun a second manuscript that is mostly ekphrastic, romantic and elegiac poems, and that explores stillness, desire, dualities, crisis, and end times. Unlike Admissions, I’m anticipating several sections, which may appear gradually as chapbooks. I’m still casting about for that elusive heart of the book. But I’m looking forward to that excavation, that scramble in the dark.

The views expressed by Open Book columnists are those held by the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Open Book.

James Lindsay has been a bookseller for more than a decade. He is also co-owner of Pleasence Records in Toronto, a record label specializing in post-punk, odd-pop and avant-garde sound pieces.